The Louvre pastels catalogue: errata and observations

This rather lengthy post will be of interest only to specialists. [Please note that it has been updated to September 2018 since originally posted.] I have earlier on this blog reviewed the current exhibition at the Louvre, and my short article on some attributions appeared in the Gazette Drouot for 13 July 2018 (a few relevant images will be found below). I also intend to publish a conventional review of the catalogue (referred to below as “XS”) in due course [this has now appeared in Apollo, September 2018, while my article on frames has now appeared on The Frame Blog]. However those outlets do not offer sufficient space for the detailed commentary provided below. Ideally they would have been made before the book went to press; but the Louvre’s own collection database, Inventaire informatisé du département des Arts graphiques (“Inventaire informatisé” below), is greatly in need of updating, so perhaps these errata will be of some use.

As always in this blog the comments below are no more than personal opinions.

p. 31. The Avertissement is far too brief for a work of this nature. There are numerous observations below (concerning especially the selection of works, the terminology of attribution and the content of bibliographies) demonstrating the inadequacy of this note. It states that XS does not cite dictionaries (although the book does cite, for example, Audin & Vial’s Dictionnaire…, and Ratouis de Limay’s Le Pastel en France, 1946 – essentially a dictionary with a few of the longer articles placed in the front of the book – as well as numerous sources which contain no more than passing references in lists). Indeed XS includes very few mentions of Pastels & pastellists (www.pastellists.com cited below as “the Dictionary”) although it reproduces many of the pastels XS refers to. The few citations are given without the exact URL of the file or the J numbers which would take readers directly to the information XS mentions. For a fully searchable and sortable concordance of Louvre pastels with J numbers, see here; this includes references to the Louvre’s 1815–24 inventaire des dessins (Archives des musées nationaux, 1DD66) which includes information about the early provenance of many items. (Abbreviated references to the numerous other bibliographic items omitted can be found in full in the Dictionary.)

p. 33. The Louvre does have the world’s finest collection of seventeenth and eighteenth century pastels. But Dresden is not the only other collection, nor is it correct that “seul le château de Versailles réunit un peu moins d’une cinquantaine…”: Saint-Quentin has more than 125, the musée Carnavalet 50, Orléans 43. Geneva more than 100, Stockholm 70, the Rijksmuseum 86 plus a good many Dutch anonymes; Warsaw a great many (mostly Polish anonymes); the Yale Center for British Art 50. (In his interview with Alexandre Lafore in Grande Galerie, été 2018, p. 51, XS goes further, stating that the Metropolitan Museum in New York and Getty possess only “quelques dizaines” – the Met actually has 50. The 2017 Petit Palais exhibition of work from the Horvitz Collection included no pastels.)

History of the collection

p. 34. There is little here about the displays in the Académie royale under the ancien régime. Guérin’s 1715 and Dezallier d’Argenville’s 1781 descriptions are not discussed and only cited indirectly (the latter in relation to Cars following d’Arnoult, although there are similar mentions of cat. nos 20, 21, 38, 95, 101, 103, 104, 117 and 126 which merit recording): they are useful sources of information about the works on display at the time (see e.g. cat. no. 126 below).

Fig. 1: The Constant Bourgeois drawing (which is reproduced in my Prolegomena) has been given various dates from 1797 (an V) on in different sources, mostly 1802–1811 (i.e. a slightly retrospective view of a late 18th century hang): what now is the justification for an exact 1802? See cat. no. 38 below for the significance of this date.

pp. 36–40. This would have been a good place to refer to Théophile Gautier’s beautiful essay “Les soirées du Louvre” (published in L’Artiste in 1858), describing a concert held in the “magnifique Salle des Pastels” which he describes in meticulous detail. Separated from the director’s apartment by one door, “chef-d’oeuvre d’ébénisterie”, the salle had been recently decorated by M. Desnuelles whose care and discretion in the choice of colours were particularly admired. The La Tour Pompadour is of course described at length. Among the other pastellists mentioned are Rosalba, Chardin and Nanteuil. This Grande salle des pastels (no. 14 in the plan in XS’s fig. 2, p. 36, but which readers may not immediately realise was on the northern side of the Cour carrée, where the Napoléon III apartments are now) seems essentially unchanged from then until when this photograph was published in La Renaissance de l’art français… in 1919 (p. 239):

Elizabeth Champney’s 1891 article described the contents of the Grande salle as “infinite riches in little space”. For those interested in such things, the discussion of the location of pastels on p. 36, right hand column, merely retypes the description in Reiset (p. II): the names of artists, but not the specific works, are given. No mention is made of the English-language guide issued by Galignani (O’Shea 1874; reprinted at least until 1888 but omitted entirely from XS) in which each pastel in each room is listed, with the numbers from Reiset’s catalogue. Thus for example we know that the Perronneau in Room 13 was Cars (“fine”), the Labille-Guiard pastels in the Grande salle were those of Mesdames Victoire and Adélaïde, Frémin was “very fine”, while the late Chardins were “full of force, truth, firmness and delicacy, and equal to any by La Tour.”

The wonderful passage from the Goncourts’ essay on La Tour (“La Tour a au Louvre une grande et magnifique place. …”) is printed but the reference is only given to the 1967 reprint of the 1882 edition: it is worth explaining that it originally appeared in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts (1867, pp. 350ff: freely available on Gallica), some 15 years earlier. As not all users of the book will read from cover to cover, the Goncourts’ specific comments on La Tour pastels should be indicated in the individual bibliographies: XS cites them only in the entries for Mme de Pompadour (to which indeed the Goncourts devoted a full discussion, and later a book); Orry; and a passing reference to Lemoyne in the list of 1763 salon exhibits. (I have indicated below some of the others.)

It is a pity too to have omitted Champfleury’s text (published initially in L’Athenaeum français in 1853, expanded into the 1855 monograph on La Tour) in which he devotes a chapter to “Son oeuvre au musée du Louvre” – it starts rather differently to the Goncourts: “Il ne faut pas juger La Tour au Musée du Louvre: on risquerait d’en garder une fâcheuse opinion.” While he praised the pastels of Mme de Pompadour, Chardin, Orry, the queen and the late self-portrait, those of the king, dauphin and dauphine “ne sont pas des oeuvres d’une grande valeur”. Later authors, such as Thiébault-Sisson in an overlooked piece in Le Temps, 1905 (which nevertheless contains an essential detail in the provenance of another La Tour pastel), expressed the wider view of the La Tours: “Le Louvre en a de superbes et d’exquis.”

Such passages offer invaluable evidence about the evolution of taste. While it may seem pointless to catalogue such ephemera, they can occasionally contain tiny facts that would otherwise be lost. Perhaps the most interesting omission from these early accounts is the lengthy chapter devoted to an “Examen critique des pastels du Louvre” by the artist Julien de La Rochenoire (better known to us today as the subject of a striking pastel by Manet now in the Getty) in his 1853 book on pastel. His discussions of almost all the 18th century pastels then in the Louvre are often surprising: his elevation of Rosalba above even La Tour’s Mme de Pompadour is of its time (few today would rate cat. no. 41 as the finest pastel in the Louvre, or even consider it to “réunir toutes les perfections échues à cette divine Rosalba”), while he explains his preference for the Chardin autoportrait à l’abat-jour over that aux besicles because the eyes in the latter aren’t placed correctly – something which at least makes us look again. I have not marked up each reference below. Nor have I listed the numerous testimonies from other artists, French or foreign, confirming the importance of the salle des pastels in their development (they included the Texas painter Frank Reaugh who published a pamphlet praising the work of Russell, La Tour and Chardin “which may be seen in the pastel room of the Louvre, as fresh and bright apparently as on the day when it was done”: Michael Grauer, Rounded up in glory…, 2016, p. 72).

One further episode in the history of this preeminent group of pastels is what happened during the second world war. The episode is discussed in Gerri Chanel’s Saving Mona Lisa, and I am most grateful to the author for sharing with me the documents she has found in the Archives des musées nationaux (sér. R6) and elsewhere. As far as I can see, XS mentions this only in relation to cat. no. 90 (La Tour’s Mme de Pompadour sent to Chambord), but makes no reference to the unsatisfactory use of underground vaults at the Banque de France until 1940. It was recognised that most pastels were too fragile to travel to Chambord, and this nearer shelter was chosen for a small number of what were then considered to be the most important works. Some 23 of the pastels in XS’s catalogue (as well as some 19th century pastels) were consigned in August 1939: they included the three Chardins (cat. nos 42-44), eight La Tours (82, 86, 88, 89, 92, 94-96) plus the so-called Madame Louise (cat. no 81); four Perronneaus (113, 114, 117, 119); two by Boze (31, 35); and single works by Loir (101); Lundberg (104, but not 103); Nattier (110); and Russell (127). Surprisingly “Boucher’s Mme de Pompadour” (cat. 28; a copy) was preferred over cat. 27; while nothing by Rosalba, Mme Roslin, Labille-Guiard or Vivien was listed. Conservation reports describe the damage suffered when the air-conditioning system broke down; the pastels were removed shortly after this was discovered. (See also cat. no. 79 below.)

Catalogue numbers

1. Le Brun Louis XIV étude

J.468.114. Is this a pastel (see comment to cat. no. 4 below)? If not why is it in the book? If yes why was it lent last year to Salzburg, when the Louvre’s official policy is not to lend pastels? I could find little in this catalogue discussing that policy, the risks of lending or the history of works lent. The only exceptions (outside Paris, since 1972) appear to be cat. nos. 22 and 35 (no. 99 did not actually travel to Geneva in 1992, although that is not evident in XS).

“Expositions” for this sheet includes “Paris, 1845, n° 1099 ou 1100”, but not Paris, 1838 or Paris, 1841 which are quoted elsewhere. In fact the Notice issued first in 1838 was essentially a catalogue of works on the walls rather than of an exhibition, and the numbers are the same in the 1838, 1841 and 1845 editions: but throughout XS the references to these various editions are given inconsistently (not detailed further below, although it should be noted that the group of royal portraits by La Tour are in the Paris 1838-45 catalogue as anonymes but omitted from XS). It is hard to see why these volumes are treated as exhibitions when Reiset 1869, essentially a new edition of the Louvre catalogue, is listed under Bibliographie (when it is listed at all – inconsistently – cats. 1–3, which are Reiset nos. 847–849, are omitted for example, while the Reiset numbers for cats 4, 5 are given). (Note however that “Paris 1869” is listed on p. 336 among expositions, but appears just to be a subsequent edition of Reiset 1869, since the museum is now national instead of impérial.) Reiset numbers are also omitted for many other works in the book. Since many of the attributions, identifications and descriptions have been changed, the absence of a clear treatment of these earlier Louvre catalogues is regrettable (for example, it takes some patience to deduce that a “Nanteuil pastel” in Reiset, no. 1201, is in fact J.552.341, which doesn’t appear in XS at all, while two pastels – a second female head in the “Verdier” group and a second probable La Tour of a royal prince, either no. 1053 or 1056 from the 1838 catalogue, disappear without mention: were they miscatalogued or subsequently lost?). Reiset numbers continued to be the ones used prior to Monnier (for example in the wartime evacuation papers mentioned above), and these discussions cannot easily be followed without a concordance.

It would also have been helpful in the lengthy bibliographies and exhibition lists had dissenting attributions and identifications been summarily indicated (e.g. “Smith 1920, as by Jones”).

There is a further problem with Expositions throughout the book: although apparently exhaustive there are numerous omissions. For example a major exhibition of pastels and miniatures took place in the Cabinet des dessins, 26 novembre – 31 décembre 1963. No catalogue was printed (although the Louvre has a list of exhibits), making it all the more helpful for XS to tell us which pastels were included (and with what attributions: selection and description are important records of the development of knowledge and taste). But although this exhibition is listed on p. 337, I failed to find any mention of their appearance in the individual entries of any of the 30 or so pastels included (even when recorded in standard catalogues raisonnés).

2. Le Brun Louis XIV étude

J.468.112. This sheet is placed after cat. 1, although in the text cat. 1 is stated to be later (as Reiset argued: indeed the sequence reverses that in Reiset and Monnier). Elsewhere however XS orders pastels by each artist in chronological order.

3. Le Brun Louis XIV étude

J.468.11. Bibliographie omits Meyer 2017, p. 189, fig. 72; she challenges the suggestion that this related to the Poilly engraving.

The physical description makes no reference to the rather prominent rope mark running horizontally across the middle of the sheet.

4. Le Brun inconnu

J.468.137. Why is this in the book when Monnier did not include it, and it is clearly outside the scope defined on p. 31? The Louvre has many other Le Brun sheets with touches of pastel that are not included (and of course by many other artists, including Simon Vouet, a number of whose pastels have recently been acquired). The question recurs above (cat. 1) and below. If exceptions are to be made, I would have included the La Tour préparations (e.g. RF 4098, reproduced as fig. 53 but uncatalogued).

5. Le Brun atelier homme en armure

J.468.141. Monnier has as attributed; I have ?cop. A method statement for degrees of attribution would clarify the distinctions XS intends.

XS repeats the traditional but misleading description of this sitter as wearing a cuirasse, when in fact he wears full armour.

6/7/8. Le Brun/?Verdier têtes

J.753.103 J.753.105 J.753.107. (The Washington sheet is J.468.149; I agree that it is by a different hand, as my classification already implies.)

See note above re Paris 1838–45 Notice and missing fourth pastel in this group.

9. Nanteuil Dorieu

J.552.173. Perhaps it should be mentioned more prominently that this pastel has not been in the Louvre since 1994; that would help readers and might even increase the probability of recovery.

The copy in Reims (J.552.177) which XS cites from Adamczak 2011 is in fact her R.14 and is discussed on her p. 76.

10. Nanteuil Ligny

J.552.238. The bibliographie omits Burns 2007, fig. 5; and Burns & Saunier 2014, p. 33 repr.

11. D’après Nanteuil Turenne

J.552.349. I relegated this to copy in 2006, well before Adamczak 2011.

14. Simon Durfort

J.6786.104. In the last four lines of the entry, XS refers to the pastel of Menestrier (J.6786.108) as the only other surviving pastel by Simon. I’m not sure that it has been published except as J.6786.109, where I tentatively reproduce “=?m/u” (a warning that the information is not sound) an image found without details on the web purporting to be in pastel and corresponding to the engraving. The resolution is inadequate to determine if it is in fact the pastel or a trimmed version of the engraving. If XS has inferred its existence only from my entry he should have cited his source so that others can assess its reliability. If XS has independently discovered the pastel he should say where and reproduce it.

15. Vivien artiste

J.77.338. The bibliographie omits Sani 1991, fig. 6.

16–18. Vivien trois princes

J.77.182 J.77.196 J.77.158.

The exhibition list includes “Paris, 1838 et 1841, n° 1050”: in fact all three pastels were catalogued, as 1048, 1049, 1050, and as anonymes (which should be noted).

The Schleißheim versions are signed and may arguably be the primary works rather than the repetitions. The dimensions e.g. for the duc de Bourgogne are 101.5×82.5 cm given as 3 pieds x 2 pi. 5 po. imperial (97.5×78.5 cm, presumably sight). Durameau’s 4 pi. 3 po. x 5 pi. 3 po. (138×170.5 cm) is simply wrong, and cannot (not “probablement”) be explained by his having included the frame (that would be 128×109 cm).

19. Vivien Max Emanuel

J.77.278. I published a long article about Vivien and Max Emanuel in The Court Historian in 2012; there’s an expanded online version http://www.pastellists.com/Essays/Chevalier_Grimberghen.pdf. Neither is in the bibliographie. There is no attempt to catalogue frames or glass systematically (see my article on The Frame Blog for further comments). A conservation report of 12 February 1943 noted the presence of glass disease on this, as well as mould on several of the Vivien pastels.

In XS’s Louvre lecture (YouTube, at 46 minutes 10 sec) it is stated that the frame was made by Vivien’s brother: as far as I am aware the only relevant document is the payment to Jacques Vivien of 174 livres on 7 November 1700 by the Bâtiments du roi for the frames on the three portraits of the royal princes (cat. nos 16–18).

Cat. nos 18, 19. These pastels were both among the royal pictures lent by the king for public exhibition in the former apartments of Louise-Élisabeth, Queen of Spain in the palais de Luxembourg from 14 October 1750, an arrangement apparently intended initially to be temporary. The two pastels by Vivien hung in the Salle du Trône, along with highlights of painting from the French school. XS refers only to the Bailly catalogue for which he gives the dates of 1751 and 1766, as nos 48/49 and 55/56 respectively, on pp. 15 (Berry) and 15/16 (Max Emanuel) respectively. The numbers 48/49 correspond to the first, 1750 edition (published by Prault), where they appear on p. 26; this edition was completely reset for subsequent ones published by Le Prieur, up to 1779 when the galleries were reclaimed for the use of the comte de Provence (by 1751 at least three editions had appeared, indicating the popularity of the show). The original initiative seems to have come from Tournehem, while later editions credit his successor, Marigny. XS omits the contemporary critiques I have found (see under Paris 1750 for full details of the pieces), two anonymous and another by abbé Gougenot, both praising the Viviens: “Sans entrer dans un éloge détaillé, il suffit de dire qu’ils sont d’une grande beauté”, according to the abbé. A fourth letter, by Jean-Claude-Gaspard Sireul, appeared in the Mercure in December 1750, but discussed only history painting.

20/21. Vivien de Cotte/Girardon

J.77.188 J.77.206. The joint presentation of these notices makes them inconvenient to read. Generally too the Louvre inventory numbers are often hard to spot, the sections called Historique covering a curious mixture of information that could be better separated out. The 1838 exhibition numbers are 1841 and 1845, not 624 and 625.

The glass on Girardon appears to have bevelled edges, and is presumably later.

22. Anonyme italien femme

J.1032.101. I have this as attr. Cristofano Allori, following Monbeig Goguel (whose name does not have a hyphen) and in accordance with the Inventaire informatisé. XS’s classification as anonyme inconnue may be safer, but a general reconciliation with the official online source is needed (I have not systematically listed the very large number of differences here). XS lists publications including Bucarest 2008 without indicating what attribution is given (this is a problem throughout the book where attributions are at issue): as that catalogue was also by Monbeig Goguel but was published after Forlani Tempesti it would be helpful to know whether Monbeig Goguel revised her view.

23. Anonyme italien moine

J.53.341 . This is a copy after Mengs of the painting of Giuseppe (or Pietro) da Viterbo in Munich (inv.. 554; Roettgen 1999, no. 214). (I am most grateful to Steffi Roettgen for drawing this to my attention.)

24. Bernard Gosselin

J.147.13 [revised]. There is extra support for the attribution to Pierre Bernard of this pastel from three small ovals I recently added to the œuvre. It is odd that XS has not consulted my biography of Bernard from which he will find that the artist settled in Marseille c.1774, not c.1764, when he was recorded elsewhere and continued to travel. It is hard to see how XS draws any conclusions about the dating of “aucune œuvre sûre de l’artiste” without referring to the Dictionary. While the chronological Bernard file http://www.pastellists.com/Chronologies/Bernard.pdf does indeed end in 1769 (it includes only dated pastels), the main artist article http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/Bernard.pdf does suggest that Mme de Saint-Jacques belongs to the 1770s. It is unclear how XS reached the conclusion that all the certain works are dated to 1769 or before unless he assumed the Dictionary was complete: in fact there is an oil painting by Bernard signed and dated 1772 which I don’t list as it is not a pastel. It is of a Marseillais.

On Gosselin’s year of birth, XS refers in broad terms to genealogists on the geneanet website (a compilation of information from sources of mixed reliability). He does not however cite the carte de sécurité issued to Alexandre Gosselin on 19 novembre 1793 when he was aged 47, making it impossible that he was born in “mars 1745”; 1746 is thus 90% certain.

25/26. Bornet Gosseaume & mère

J.171.105 & J.171.107. Mme Gosseaume’s year of death 1788 is mine, as is the Mercure reference etc. Although there is a reference to me in the entry, it is oddly placed. XS quotes one J number in the bibliographie, but wrongly (“J.171.165” will not find the pastels on searching).

The bibliographie omits A. P. de Mirimonde, L’Iconographie musicale sous les rois Bourbons, 1977, p. 55.

27. Boucher Tête

Neither the identification of the sitter nor the status of this version are beyond dispute. It would have been particularly interesting to see an image of the signature which cannot be detected in the image of the pastel, and was not easy to see under exhibition lighting.

28. D’après Boucher

J.173.109. p. 79: “Jean-Claude Gaspard de Sireul” had no particle: see my article http://www.pastellists.com/Essays/Sireul.pdf where the works mentioned are discussed. The bibliographie also omits Seymour de Ricci, “La collection du baron de Schlichting”, Revue archéologique, xxiv, 1914, p. 339, where the work is described as formerly Sireul’s.

As noted above, this was the “Madame de Pompadour” by Boucher selected in preference to no. 27 for wartime shelter in the vaults of the Banque de France. To follow these changing tastes it would have been helpful to note that Bouchot-Saupique 1930 has cat. no. 27 as “école de Boucher”, while 28 was “attributed” to him.

29/30. Attr. Boucher Dénicheur/Oiselière

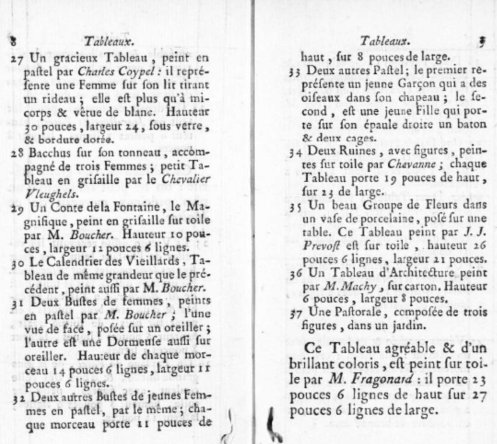

J.173.873/J.173.874. These do not seem to bear the new attribution XS proposes. It would be interesting to know which Boucher specialists agree with the promotion: are they even related to Boucher at all? While XS recognises that it is uncertain that these are the pastels from the Blondel sale, he states that those were catalogued by Rémy as autograph works by Boucher (“comment imaginer qu’il se soit alors trompé?” he asks): but that isn’t the case. The catalogue mentions Boucher explicitly for the four preceding lots “par M. Boucher” and “par le même”, but gives no artist’s name for lot 33, while the next lot is by a different artist:

So far from endorsing the attribution, one can read the catalogue as implying that Rémy didn’t know either.

Among the oeuvres en rapport should be cited the pastels were those that appeared in the Jules Lecocq sale, Amiens, Ducatelle, 16–17.iv.1883, Lot 304 (unillustrated), where they were described as after Huet, not Boucher. This is particularly interesting in view of the rather good oil given to Huet in the New York sale (Sotheby’s, 28 January 2005, Lot 553) which XS cites without discussion, although the complexities of the repositioning of the two wooden fences in the backgrounds into the opposite pastel suggests that a longer discussion is in order.

31. Boze auto

J.177.101. The pastel is discussed in my article on the very similar portrait of Pierre-Paul Nairac http://www.pastellists.com/Essays/Boze_Nairac.pdf.

The conservation report of 12 February 1943 commented in detail: “Les taches grisâtres sur le visage paraissent provenir surtout de l’emploi de blanc dit d’argent pour des restaurations. L’étendue de ces taches est telle que l’aspect du pastel est devenu très désagréable et j’estime que l’on ne pourra l’exposer après la guerre dans cet état. Il faudrait donc voir s’il n’est pas possible de faire exécuter une restauration consistant dans l’enlèvement de ces “repeints sur pastel”, ce qui permettra de récupérer une certaine quantité de matière ancienne et ensuite d’ajouter le minimum de restaurations indispensables, exécutées cette fois à la craie.”

32. Boze Mme Boze

J.177.177. The “copie avec variants” listed in the œuvres en rapport has been deleted from the Dictionary as it is in my opinion a later pastiche (it shares the characteristics of a fairly large group of such pastiches apparently produced by a single hand, and mostly signed with fictitious initials).

The description of the support in the left-hand column indicates that it has been primed with a ground substance (usually pumice stone), while in the adjacent text XS refers to the surface being rubbed with pumice stone, a quite different process.

35. Boze comtesse de Provence

J.177.313. It seems likely that this, rather than cat. no. 32, was the “Mme Boze” pastel sent to the Banque de France in 1939, as the Reiset number, 673, is cited with it in the memorandum.

36. Carriera fille

J.21.2378. Bibliographie: Toutain-Quittelier 2017b, fig. 120 is omitted here and from the other Carrieras.

An explanation of the curious bright patch along the sitter’s left cheek (stumping, intensified by subsequent light changes or later intervention?) would be interesting.

37. Carriera gouvernante

J.21.0442. The inscription should be read “apud D. Crozat” not “apad”, nor is there any reason to question the D, no doubt for dominus. I think it simply means “chez le sieur Crozat”.

38. Carriera Nymphe

J.21.1727. p. 93: XS omits several items from my bibliography, most notably the important discussion in Anon. 1750, the “Lettre d’un amateur de Province sur le secret de fixer le pastel”, Journal œconomique, février 1758, pp. 63-65: see Treatises. This pastel and the Anon. 1750 text are discussed at length in my article on Loriot (online at http://www.pastellists.com/Essays/Loriot.pdf ), which appears in the bibliographie on p. 342 as Jeffares 2015, but has apparently been deleted from the bibliographie on p. 93 for cat. 38.

In the œuvres en rapport, pastellists.com is cited, followed by “On peut également ajouter…” followed by a work which is in fact in my list, J.21.1778 (and was from before the sale date).

The frame on this work was evidently added after the date of the Constantin Bourgeois drawing (v. p. 34 above).

40/41. Carriera Mme & Mlle Languet de Gergy

J.21.054/J.21.0575. See my exhibition review and post for the girl’s date of birth, the mention in Carriera’s diaries and the apparent age which I have solved with the Regensburg birth in 1717.

The headline to no. 40, “Anne Henry, épouse de Jacques Vincent Languet de Gergy (1667–1734)” might appear to suggest that those are her dates; they are in fact his. Hers were c.1695–1775.

These were surely the pair exhibited in Paris 1802, no. 249.

42/43/44/45. Chardin

J.219.103/J.219.115/J.219.136/J.219.13.

On Chardin’s name (Jean-Siméon, not Baptiste), see my exhibition review.

The inv. no. for 45, the autoportrait au chevalet, is given as Inv. 31478 (pp. 106 & 334) but the accession date shows this must be wrong. The Dictionary has RF 31748 (as given in the Inventaire informatisé), while RF 31770 is given erroneously in Chardin 1979. Incidentally the Inventaire informatisé reports “Cette œuvre n’est pas visible actuellement dans les salles du Musée” which is not helpful; I haven’t checked the 118 other works.

Bruzard, who owned three of these pastels (as well as the Prud’hon, cat. no. 124), deserves to be fully identified: he was Louis-Maurice Bruzard (1777-1838), économe du collége Louis le Grand, and a copyist (see here). His posthumous sale ran from 23 to 26, not 24, April 1839 (Reiset unaccountably has June); cat. no. 42 was Lot 57, not 37.

Among the œuvres en rapport for no. 42 is listed the Orléans version (J.219.107), with Livois in 1790 and inscribed verso “offerte à Mlle de la Marsaulaye, élève de Chardin, par son maître”. Although Chardin died in 1779, Salmon suggests that Mlle de La Marsaulaye acquired it after Livois and that she may have been a pupil of Chardin. But Félicité Poulain de La Marsaulaye (née 1780), who married the vicomte de Rochebouët in 1805, was too young to have been a pupil, and the inscription cannot be strictly correct. The Dictionary has more steps in the provenance.

As XS notes on p. 104, some of the records of Chardin pastel autoportraits (e.g. that in the Pigalle inventaire or that offered to Marcille and described in a letter of 1890) do not permit us to decide which (if any) of the Louvre autoportraits they relate to: but both appear in two catalogue notices, 42 and 43, on pp. 100 and 104.

Among the œuvres en rapport for no. 44 is the Chicago version, which it is suggested may be the signed pastel of a “vieille femme” in the Jean-Louis David sale, while noting (as Pierre Rosenberg has) that that could equally well described the Besançon Rembrandt copy. It is worth noting however that the same catalogue included two “Chardin” natures mortes, “pastels d’une qualité remarquable”, which are most unlikely to be correctly described.

Omitted from the list of copies of no. 44 is that by James Wells Champney (J.219.139) which we know from an 1897 photograph of his studio where a number of his copies of Louvre pastels are visible (it gives an indication of the industrial scale of the copying of Louvre pastels):

The Chardin literature of course is vast. However it is curious not to refer explicitly to Derrida (the Paris 1990 exhibition is indicated but the bibliographie only mentions Séverac). Ewa Lajer-Burcharth and Hannah Williams are among the more recent omissions. Edinzel’s work is a Cornell University Ph.D. thesis of 1995; his forename is Gerar, not Gérard. Petherbridge 2010, fig. 194 reproduces the autoportrait aux besicles, and discusses it with the 1939 Giacometti drawing it inspired (also omitted from the oeuvres en rapport) which may be seen on the Art Institute of Chicago website (where it is absurdly described as after Maurice-Quentin de La Tour, particularly puzzling given that Chicago own a version of one of the Chardin pastels copied). Another omission is the passage in the letter from Cézanne to Émile Bernard of 27 juin 1904 which itself has given rise to a secondary literature of analysis of what he meant (see references in Ben Harvey’s blog post, as well as the delightful Prigent & Rosenberg 1999: the book may look introductory but it is packed with thought and information). His self-portrait appears within the still-life of Chardin et ses modèles exhibited by Philippe Rousseau in the Salon of 1867. Chardin’s influence on other artists was not confined to the modern school: in the portrait of Jeaurat attributed to Étienne Aubry (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco: see Rosenberg & Stewart 1987, p. 107), the arrangement of clothing is strikingly similar to cat. no. 42, as noted by Puychevrier in 1862 (p. 27).

Also omitted from the bibliographies is one of the more interesting early discussions of the autoportrait aux besicles and that à l’abat-jour is in Champfleury’s 1855 monograph on La Tour (pp. 88f) where the works are lavishly praised, and contrasted with La Tour’s own portrait of the great master (see below). And while the splendid passage from Proust is quoted in the introduction (omitted however from the index), it is the passage from Reynaldo Hahn’s diary, relating his visit to the Louvre with Proust in 1895, that has the most interesting comparison of Chardin, La Tour and Perronneau (it is reproduced in my Florilegium).

Perhaps finally one should note the exhibition in which the Louvre pastels formed the centrepiece: Paris 1957a. In the anonymous but curious review of “French portraits at the Orangerie”, The Times, 9 January 1958, which mounted a forceful British attack on “this pretty-pretty school”, the Chardins (and one La Tour, cat no. 89) were exempt:

it is difficult to come away from this exhibition without feeling that Chardin bestrides it like a colossus.

46. Coypel Allégorie

J.2472.333. The title was previously “rendant grâces” but is now just “rendant grâce”. The reference to Salmon 1999 should be to Salmon 1999a.

48. Deshays tête

J.2704.107. Again it is unclear why this sheet is included.

The Kraemer jeunes filles cited as not by Deshays may be found in the Dictionary as copies after Boucher (J.173.242 and J.173.227).

49. D’après F.-H. Drouais

J.2818.185. For “Tauzia, 1879” read “Both de Tauzia, 1879”.

It seems eccentric to headline this entry “portrait présumé de Marie…, épouse de Pierre Grimod-Dufort, seigneur d’Orsay”, when at the time the original was painted Grimod had been dead for 24 years and she had been married to her second husband, Le Franc de Pompignan, for some 15 years.

The entry assumes that the Caulaincourt painting has been correctly identified, which appears to depend entirely on a “mention” (by which XS presumably refers to what Join-Lambert & Leclair refer to as an “inscription sur le portrait” “mariée en 1747 à Dufort d’Orsay”, perhaps the words painted beside her head: but it is far from clear when they were added). XS does not state whether he has seen the pastel’s frame, which had (to judge from the old photograph, below right) an equally convincing inscription painted on the oval frame’s flat frieze “Marie Louise Albertine Amélie née Princesse de Croÿ…Empire Romain Comtesse d’Orsay” (there is also a Louvre plaque with Boze’s name attached, but the lettering of that is later):

The matter is made all the more complicated by the existence (which XS does not mention) of a (pseudo-)pendant in an oval frame of identical moulding (Galerie Pierre Brost, above left): an oil of Grimod’s son Pierre-Marie-Gaspard, comte d’Orsay (his face identical to that in the Valade pastel – XS’s fig. 31, see cat. 72 discussion below), but shown in armour, as a kind of fancy dress that matches the “en sultane” mode of the pastel). We agree that the pictures all date to 1772 or thereabouts, so in the absence of convincing alternative iconography the only discriminant is whether the sitter is 24 (Croÿ) or 41 (Caulaincourt). We know how hazardous that choice is, but my inclination would be the younger woman.

[Postscript: Ólafur Þorvaldsson has kindly drawn my attention to the Drouais studio version (in oil) of the Louvre pastel exhibited in Copenhagen 1920, no. 81, which is of the princesse de Croÿ, shown this time in ordinary costume.]

50. Ducreux auto jeune

J.285.101. Although clearly by him, is this actually of Ducreux? The face is quite different from the later self-portraits, and the eyes are blue instead of the brown seen in the other self-portraits (oddly his description in the 1792 brevet for the Garde nationale says “les yeux gris bleus”, but the remainder “le nez un peu retroussé, la bouche fort bien, le front découvert, le menton pointu et fossette au milieu” agree with the other self-portraits but not this). The signature and date are not completely convincing, and the identification is based on an inscription on the back which is clearly 19th century.

Omitted from the bibliographie is Salmon’s own article in Cabezas & al. 2008, p. 45, where the pastel is erroneously reproduced as c.1795/98.

The question of the progression of Ducreux’s talent and the date of association with La Tour is indeed problematic (XS is not the first since Georgette Lyon to ask – p. 114), but I don’t think it is solved by postponing a meeting until Ducreux was 48 years old, when La Tour was senile and Ducreux could only have been shown his work (which he would already have seen at the salons) rather than see him working. Further XS overlooks examples such as the magnificent pastel of Weirotter (J.285.742) from 1769 which is not only of outstanding quality, but intensely latourien. One should also note the roll call of eminent families Ducreux portrayed from the start of his accounts (1762 on), suggesting that work was directed to him from a studio such as La Tour’s. It is for these reasons that I continue to believe it possible that Ducreux was close to La Tour by the 1760s.

51. Ducreux auto vieux

J.285.151. The donor of inv. RF 2261 (fig. 16) was not the hybridly spelled “Frédéric Anthony White”, but Frederick Anthony White (1842–1933), a well-known British amateur. On p. 114, left column, I published the Louviers pastel (J.285.149) as probably the Salon de 1796, no. 145 (=?J.285.148) in 2012.

XS says nothing about the expensive, elaborate and surely later châssis à cléfs on which this must have been remounted, standing in contrast to the very loose weave of the original canvas.

52. Ducreux Madame Clotilde

J.285.272. Here in particular the location of the Louvre inventory numbers is particularly confusing, placed at the end of often long Historique paragraphs which contain provenance and conservation information.

p. 117: J.285.276 is correctly cited for a work which is in a private collection (not exactly “non précisée” but accorded the proper discretion for a collector), but inexplicably states that it faces left.

56. Ducreux Joseph II

J.285.413. See my Gazette Drouot article. XS does not report that the Louvre pastel (second from right below) is a copy of the figure of Joseph from the famous Batoni painting of 1769 (detail, far left: Vienna, KHM, sent there by Batoni from Florence on 27 June 1769, as reported in the Gazette de Vienne, 12 July 1769 – a few months before the date XS gives for the Ducreux). This has been in the Dictionary since the first edition in 2006.

Kernbauer & Zahradnik 2016, which reproduces most of this group and the versions in Austria, is omitted from the bibliographie; it includes another pastel copy of the Batoni, no doubt by Ducreux as well; the sitter’s right arm is altered (far right). There was at least one more version, given to the comtesse de Brionne and lent by her for the Cathelin engraving published in 1774 (second from left): in that version Ducreux follows the Batoni more closely, including the full display of the stars of the Austrian orders on his coat. In the Louvre and Klangenfurt pastels the drapery is changed (and more of the cordon bleu of the Saint-Esprit is seen), no doubt for the better reception at the French court. Perhaps Ducreux’s failure to paint the emperor from life bears out the statement in Michael Kelly’s Reminiscences (1826, i, p. 207) that “Joseph had a strange aversion from sitting for his portrait.”

Among the other œuvres en rapport omitted is a drawing from the Louvre itself: Jakob Matthäus Schmutzer, inv. 18783.

p.122 left column, top line “jeune portraitiste formé par Maurice Quentin de La Tour”: presumably this phrase was written before the discussion on p. 114 implying a later date for Ducreux’s association with La Tour.

p.122: discussion of the two KHM replicas: XS reports his change of mind about the identity of GG-8732, but there is a further confusion about GG-2123 which has been inventoried in Vienna as of Maria Christina.

57. Ducreux dame âgée

J.285.31. Salmon 2008 in the bibliographie here does not appear in the bibliographie on p. 345, but it is of course a reference to his contribution to Cabezas & al. 2008.

59. Mme Filleul, comtesse de Provence

J.316.139. It is reproduced in Boze 2004 as “attributed to Filleul” and mentioned in articles by Laurent Hugues and by Gérard Fabre, although I believe the original suggestion came from Joseph Baillio. I published it as by her in 2006. Blanc 2006 is also omitted from the bibliography.

61/62. Frey Rozeville couple

J.47.1124 & J.47.1125. The proposed identifications (on the basis of the fragmentary inscriptions) are mine. On their dates and the attribution to Frey, see my exhibition review and my Gazette Drouot article. Here is the signed and dated Lefèvre pastel for comparison:

M. de Rozeville’s dates were 1706-1768, not “1720-1730? – 1791-1820?”, while Mme was 1727-1762, not “1725-1787”. (These are found in baptismal records, inventaires après décès, placards de décès etc.)

63. Gandolfi garçon

J.337.101. On costume/date grounds alone Ubaldo would seem more likely.

The reference to the exhibition “Paris, 1983” leads to a different event on p. 337 (the “Institut de France” exhibition).

64. Gautier-Dagoty Crébillon

J.3408.102. p. 134.”Longtemps négligée &c.”: the pastel is among the anonymes in Ratouis de Limay 1925 (p. 47). It was sold to the Louvre in 1839 as by La Tour, and a report was obtained from M. Cailleux (Archives des musées nationaux).

XS properly credits my discovery of the 1777 text, but misspells the title: it is Annonces, affiches, nouvelles et avis divers de l’Orléanais not Orléannais.

Jacques-Fabien Gautier’s dates, given by XS as 1710? – 1781?, can be found in the Dictionary, as Marseille 1711 – Paris 1785 (he was born on 6 September in the parish of Les Accoules).

65. Gounod Duvivier

J.3546.103. In historique, Nocq was the biographer of the subject (Duvivier), not the artist (Gounod).

66. Gounod marquis de Wailly

J.3546.11. The suggested identities cited by XS in his last paragraph are those proposed (with all necessary reservations) by me where the Dictionary states: “…traditionally described (based on an illegible inscription) as of ‘Mr de Wailly, …général’, it could be of Vincent de Wailly, receveur général des impositions d’Amiens. It does not much resemble the Vincent caricature of the grammarian Noël-François de Wailly or the Pajou bust of his brother the architect Charles de Wailly.” Since there was no “de Wailly, fermier general”, one cannot rule out a non-financier since the reference is wrong. Further “fermier” in the inscription is completely illegible and may be an erroneous interpolation.

67. Greuze L’Effroi

J.361.21. The title would make more sense as L’Effroi, a personification, and the title it was given when it first entered the Louvre (Paris 1990 cat.) and in earlier sources (I could find no general statement about titles of works, many of which – including “autoportraits” – must be new). The bibliographie omits Munhall 2008, no. 10, fig. 34. The provenance is out of sequence, with the 1892 sale preceding the 1875 one (curiously the same error is found in the Dictionary, where the text was corrupted inadvertently).

The arms are reproduced too small to be deciphered (the rather coarse screening is a criticism of all the reproductions): but from a larger photograph they can be blazoned as: “De …, au chevron de … accompagné en pointe d’un [loup, renard, chien?] contourné de … , la tête contournée, et d’un soleil de … naissant et rayonnant en chef à dextre, au chef de … chargé de trois coquilles de …”. They bear a comital crown, but nevertheless are not to be found in any of the standard armorials (d’Hozier, Borel d’Hauterive, Jougla, Rietstap etc.). It seems possible they may be bogus.

68. D’après Greuze jeune fille

RF 35773 [no J number]. Should this xixe copy of a Greuze oil painting be included in a catalogue of the Louvre’s xviie–xviiie pastels?

69/70. Anonymes

J.361.347/J.9.5148. The entries for these works are hard to follow. Alphabetically they are linked to Greuze, although only one is in fact connected (XS suggests the other is too). As they are not the same size they are not even pendants (Reiset 1869 has only one of them, no. 1406; the no. 1957 which XS prints as in Reiset 1869 is a reference to Both de Tauzia 1879). The inv. nos. are reversed: in fact 69 is 34898 and 70 is 34897. In the list of œuvres en rapport for no. 70, XS includes a sale at “Roseberry’s” (for Roseberys); the same typographical mistake is regrettably found in my entry for J.9.5148. XS also includes a third version from an internet auction in Dijon, Sadde, 30 juin 2017, Lot 2: but this lot was an unrelated drawing by Arthur Gueniot (there was no pastel in that sale).

XS includes no list of copies for no. 69 = J.361.347 in the Dictionary, where one will be found. To these should perhaps be added Adèle Lemaire, whose application to copy the pastel Jeune fille pleurant son oiseau can be found in the Archives des musées nationaux, sér. DA 5, cabinet des dessins, 2 mai 1870; we do not know if her copy was executed.

71. Hoin Tête

J.4.229. “Claude Jean-Baptiste Hoin”: his baptismal name was just Claude (see Dictionary for discussion). My entry should have been cited since I suggest a possible earlier provenance: [=?F. de Ribes Christofle; Paris, Petit, 10–11.xii.1928, Lot 37 n.r.]

72. ?Høyer, Christian or Frederick

J.85.11335. See my Gazette Drouot article. XS cites an early version of my reidentification of this portrait based on my detection of the Elephant order. In fact it is now (since 2017) J.85.11335 [olim J.83.1016] of Christian VII, as we know from the engraving of it by John Sebastian Miller, who may have done the pastel (“ad vivum” in the legend), but which I include as English school as there are no other recorded pastels from his hand. It was published in the London magazine for August 1768 to coincide with Christian’s trip to England. (There is no c in the Danish spelling of Frederik, and no K in the French spelling.)

p. 145 fig. 31. XS reports of this pastel, published by Méjanès under an attribution to Drouais, that “Jean-Jacques Petit en a légitimement rendu la paternité à Jean Valade” and cites a 2017 publication. But in fact the work is reproduced (in colour) as by Valade on p. 529 of the 2006 print edition of the Dictionary, and remains there online (J.74.228; where a reference will also be found to Olivier Ribeton’s 1992 suggestion of Valade).

Given that Ribeton, Jeffares and Join-Lambert & Leclair 2017 all concur that this is of comte d’Orsay it is strange that XS now qualifies this portrait as « présumé » (v. cat. 49 above).

73. Kucharski Mme Barbier-Walbonne

J.438.104. Why is Kucharski’s first name Aleksander given in Polish form when other names (e.g. “Stanislas Auguste”) are not?

On Kucharski and Stanisław August, see my article “Polska i jej elity na tle popularnosci portretu pastelowego w XVIII-wiecznej Europie”, Rocznik Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie, vi, 42, 2017, pp. 137–55.

Mme Barbier Walbonne, whose death is given only as “avant 1837”, died on 31 October 1818 at Bernes-sur-Oise.

“années 1808–1810. Elle pourrait être un peu antérieure.” But is XS claiming it is eighteenth century? If not why is it in the book? In the comparative example repr. as fig. 32, XS gives its details from two sales in New York, Christie’s 10 janvier 1996, lot 251, and Christie’s East, 25 novembre 1997, with the lot number for the second sale omitted. This is exactly the form and (careless) omission that occurred in my entry for J.438.205 (until June 2018; now corrected).

74. Labille-Guiard Bachelier

J.44.118. This is no. 784 in Reiset, not 783.

On the donor (of this and Vincent), Monnier only gave Mme Nannoni; see http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/Bansi.pdf for her biography.

A general problem with bibliographies is the inclusion of references to books which do no more than repeat the lists of an artist’s salon exhibits. Thus de Léris 1888 (whose list of course includes Pajou too, although he is not cited at cat. no. 76). This too is what is found in the source which de Léris obviously drew upon, Fidière 1885, at the cited p. 43; while two pages later there is a significant discussion of the pastel itself: “fine et spirituelle…d’une exécution très habile et d’une charmante couleur.”

75. Labille-Guiard Vincent

J.44.276. Bibliographie omits Denk 1998, fig. 38; Prat 2017, fig. 423. List of œuvres en rapport follows my J.44.278, which was my identification. The copy sold in 2012 was identified by me. The suggestion in the provenance that this was the picture in Mlle Capet’s inventaire, and that “M. Ansieux” was “[?Jean-Joseph Eléonore Ansiaux (1764–1840), peintre, élève de Vincent]” are mine (unacknowledged). (Note that [ ] in my entries usually means information I have added to previously published data.)

76. Labille-Guiard Pajou

J.44.232. Quincay needs a ç.

My bibliography includes also Renard 2003, p. 147 repr.; XS omits all reference to this work (which includes Perronneau, Huquier, p. 68 in Renard; Perronneau, Cars, p. 84 in Renard; Lundberg, Boucher, p. 101 in Renard; Mme Roslin, Pigalle, p. 114 in Renard), Chardin, auto à l’abat-jour, p. 122, Loir, Belle, étude and pastel, pp. 132 and 133, Boze, autoportrait, p. 139). Similar publications are cited, e.g. Julian Bell’s 500 self-portraits.

Expositions: omits Paris 1963 despite being listed in Passez (see note to cat. 1).

Quotation from Pahin de La Blancherie: it is unclear that this was about the portrait of Vien, not of Pajou. The source quoted is Ratouis de Limay 1946, where however different spelling is given (e.g. “complettement”). The passage in its full context (and with single t) may be found in the Dictionary, at http://www.pastellists.com/Misc/Exhibitions_1776_1800.pdf (p. 10 of the current edition of the pdf), where you can see that the passage comes from the Nouvelles for janvier 1783, the month before Pajou was exhibited.

On the composition, see my comments on cat. no. 126 below.

The pastel, its frame by Claude Pepin and his death on 13 January 1782 are discussed in my Prolegomena, omitted from the Bibliographie. This would have been a good case to discuss pastellists’ relationships with framers.

77. Labille-Guiard Beaufort

J.44.136. This was not in “Paris 1927, no. 75” in either the livret or the catalogue commémoratif.

78. La Tour auto (Neilson)

J.46.1009. Is this entry out of sequence? It is far later than the following items, even if the work of which it is a replica is early. The argument can’t be that self-portraits are brought to the front (although this would explain the sequence of the late Ducreux, cat. no. 51), as cat. no. 91 is far later.

XS appears to have made extensive use of my research on Neilson, including my discovery of the pastels by him in a Scottish collection, identifying Dupouch etc. Incidentally they were, but are not now, at Amisfield; they are in a different house. The information he presents is not in the Curmer biography or the Christie’s sale catalogue. In my Neilson article (until I corrected it in June 2018) a typographical error gave Curmer’s first name as Alfred when in fact it is Albert. On p. 339 XS prints my erroneous Alfred.

However XS has simply repeated the erroneous provenance inferred by Christie’s (and followed too by me until 2018) based on the inscriptions rather than independently verifying them. In fact Antoine-Marie Lorin died in 1859, not 1871; and the H. Lorin who received the pastel on the death of “Antonin” was not Antoine-Marie’s son Henri (1817–1914) but the latter’s nephew Henri (1857–1914), brother of the Henriette-Louise (1852–1930) who married Paul Gautier de Charnacé. For the steps see my Neilson genealogy.

Omitted from the bibliographie is Maurice Tourneux 1904a, where the pastel is discussed on p. 36, and reproduced p. 13; it was then in the Lorin collection. It is curious that it escaped B&W’s catalogue, but it was not unpublished when it emerged in 2005.

79. La Tour Mlle de La Fontaine Solare

J.46.2926. I have all the “œuvres en rapport” listed here, not just one as the text suggests. The identification of the source of Stanisław Leszczyński’s pastel is mine. (There is e.g. no mention of the association in the Voreaux 2004 catalogue of Stanisław’s work, where the pastel is included as no. 19, p. 190f.) But there are other related works: the curious Mme d’Authier de Saint-Sauveur, whose condition precludes a determination of its status but seems most likely “wrong”; the autograph Mme Restout recently acquired by Orléans; and the obvious pastiche, J.9.6183.

In the historique, XS notes that the pastel was seized by the Nazis before January 1941. In fact, in common with other pictures from Jewish collections, it was first required to be deposited in a vault (no. 63 in this case) in the Banque de France (along with the 23 Louvre pastels noted above). It was then transferred to the Jeu de Paume on 29.x.1940 before being taken to Germany.

80. La Tour Frémin

J.46.1819. Bibliographie omits Denk 1998, fig. 15; Williams 2015, fig. 5.2, as well as the Goncourt (1867, p. 350: “la coloration puissante”). It is worth citing Lady Dilke’s assessment (1899, p. 164) with which I concur: “the Louvre collection is of the highest value and contains at least one of Latour’s finest male portraits, that of the sculptor René Fremin.”

Since Mariette described the pastel shown in 1743, hors cat., as of Frémin “jusqu’aux genoux, fait en sept jours” I have two J numbers, J.46.1818 and the Louvre’s J.46.1819; XS may well be justified in conflating them. This may or may not be related to the other puzzle: the pastel is mounted on a châssis à clés, of a kind very rarely used for 18th century pastels (although the exceptional size might explain it), and has had a batten attached to one side to extend the work, apparently to fit into the present frame. It it is tempting to assume that this was done around 1852, a date that appears on some newsprint used to line the back. Photographs in the file demonstrate that the batten was applied outside the canvas, which folds between the stretcher and the batten. That would seem to preclude the original state having been bigger – unless there were an earlier, more radical transfer onto the stretcher. That would explain why the canvas that projects from the back has been fixed less tidily than one might expect. But such a transfer is difficult to reconcile with the exceptionally high finish of the work. And while one should not take the story of its being finished in seven days too literally, it might suggest that there was an earlier, less finished version.

To understand this fully it is necessary to establish the detailed provenance (this genealogy may help). XS omits the steps between Frémin’s posthumous inventory in 1744 (as cited by Rambaud) and the acquisition by the Louvre from “Mme Piot” [recte Piat: she signs “fe Vor Piat”] in 1853, noting only that it might be the pastel that had been offered to the Louvre previously. In fact Louvre documents now in the Archives des musées nationaux etablish that the pastel passed to Frémin’s grandson Alexandre-César-Annibal Frémin de Sy (1745–1821), mousquetaire du roi, who left it to his sister, Mme Noël (her name is omitted from all standard genealogies, and her youth suggests she can only have been a half-sister of the marquis de Sy: in fact detailed research in the parish registers at Sy confirms she was the illegitimate daughter of Marie-Charlotte Noblet, the 21-year-old daughter of a local carpenter in Sy, and bore only her family name, as Adélaïde-Cécile Noblet, until her marriage to Laurent Noël). (Since César-Annibal was an émigré during the Revolution, his wife – who had remained in Sy – dying, his château being demolished and all its contents sold, it is likely that during the Revolution the pastel had remained with his father’s widow, who survived until 1817.)

It was Mme Noël who offered the pastel to the Louvre, first in 1829, again in 1834; she was told that the pastel didn’t suit the Louvre, the sitter not being a celebrity. After her death in 1844 it passed to her daughter Marie-Catherine-Clémence Noël (1808–p.1854), who had married Victor-Louis Piat in 1832 (hence “femme Victor Piat”). He was a worker in the clockmaking industry, but lost his job around 1850 and failed to obtain further employment. With three daughters to support Mme Piat wrote a series of increasingly desperate letters to sell the pastel to the Louvre, eventually dropping the price by a third to the 2000 francs for which it was finally acquired 18.xii.1853.

The condition report obtained more than 18 months earlier provides key information about the pastel: it was in perfect condition despite the fact that the frame had suffered “quelques ravages du temps et du différentes déplacements du tableaux”; the dimensions (sight size) were 90×73 cm, and it corresponded exactly to the 1747 Surugue engraving (the aspect ratio of the print and pastel in its current form are both 1.23, while without the extension the ratio would have been 1.27). It being unlikely that the family had reframed the work, the spatial arrangement in the print indeed suggests that the extension has been in place from the very beginning.

Oeuvres en rapport: XS notes that the pastel was engraved by Surugue (who was born in 1716, not 1710, although the error is found in several reference works). On 22 décembre 1743, months after the pastel was exhibited, and two months before his own death, René Frémin was parrain to Surugue’s daughter Marie-Élisabeth, baptised at Saint-Benoît. She died soon after.

The adoption of the spelling “Fremin”, without an acute, is curious – pp. 160, 162; but with the accent in the index, XS’s previous works (Debrie & Salmon 2000, La Tour 2004) and most modern sources.

81. Attr. La Tour, Religieuse

J.46.2183. See my Gazette Drouot article. The entry is very confusing, starting from the beginning “L’œuvre est entrée au Louvre comme attribué à Maurice Quentin de La Tour”: in fact it was given as by him. It was rejected by Monnier but when I saw it with Jean-François Méjanès in 2004 we both thought it had more potential and agreed on at least reinstating it as “attribué à” La Tour. Looking at it again, and allowing for a curious problem with the nose (perhaps explained by earlier restoration) I now think it is probably autograph. XS appears to think so too, but has inexplicably retained the “attribué à” qualification. A tweet by the Louvre suggested that the attribution to La Tour was recent, to which I responded with some of the above. The claim that the pastel entered the Louvre as an anonyme was repeated in XS’s Louvre lecture (available on YouTube, at 6m00 in); further it was claimed that the misidentification as Madame Louise was “généralement retenu” even though I rejected it in the 2006 print edition of the Dictionary. The exhibition history omits Paris 1888 – and Paris 1963 (see note at Cat. 1 above), where indeed the identification was questioned (“portrait présumé de”). The historique given by XS, which starts with “Georges [sic] de Monbrison”, is incomplete; reference to the Dictionary when XS was writing would have extended this back to 1851, and another researcher (Ólafur Þorvaldsson) has recently kindly drawn my attention to the 1863 sale. Subsequently I noted that the pastel had been lent to an exhibition in Paris in 1874 (as of “Mlle de Charolais, fille de Louis XV, en carmélite, très-beau pastel de Latour”) by Maurice Cottier, the painter and collector who co-owned the Gazette des Beaux-Arts. Cottier probably bought it at the 1863 sale. After his death it passed to Monbrison, who was the nephew of Mme Cottier. The full provenance should be:

Baron de Silvestre; Paris, 11.xii.1851, Lot 234, anon. René Soret; vente p.m., Paris, Drouot, Perrot, 15–16.v.1863, Lot 152 n.r., as by La Tour, ‘très beau pastel d’une conservation remarquable’, ₣360. Maurice Cottier 1874; desc.: le neveu de Mme Cottier, née Jenny Conquéré de Monbrison, George Conquéré de Monbrison (1830–1906), château de Saint-Roch 1888; sa nièce Laure-Augusta-Marianne de Monbrison, Lady Ashbourne (1869–1953); don 10.vii.1920 ‘au désir de sa mère’ [Mme Henri-Roger Conquéré de Monbrison, née Élisabeth-Louise-Hélène Hecht (1848–1912)].

Since it was given in memory of Lady Ashbourne’s mother, that name should be given.

During the war, this was one of the pastels damaged while stored in the vaults of the Banque de France. “Un très léger point de moisissure sur le portrait anonyme de Madame Louise de France a été retire par Mr Lucien Aubert”, according to a contemporary report; it is not clear if this was the spot on the nose mentioned above.

82. La Tour Le dauphin

J.46.2126.

It is unclear why XS now refers to Louis le dauphin as “le dauphin Louis Ferdinand”. It is not the form given in the almanachs royaux or in Jougla de Morenas, in XS’s previous work, or on p. 331 of XS (where the normal style is given).

There is no discussion of the curious appearance of the face, which presumably is the result of some form of rubbing.

83. La Tour Orry

J.46.2431.

Omissions from the bibliographie include Champfleury 1855, p. 89; Graffigny 2002, vii, p. 115 repr.; and James-Sarazin 2016, i, p. 521 repr.

On Duval de l’Épinoy, Mme de Graffigny etc. discussed p.168 one should cite my essay http://www.pastellists.com/Essays/LaTour_Duval.pdf, not simply pastellists.com. My other essay http://www.pastellists.com/Essays/LaTour_Rieux.pdf would also be helpful.

The copy in Sierre mentioned in the œuvres en rapport is J.46.2433, repr. in the Dictionary.

There is no suggestion for the maker of the frame in stuc doré with the curious mark DL. The question is discussed Pons 1987 p. 42, of which there is an illustrated version online in https://www.theframeblog.com/2017/07/12/18th-century-french-frames-and-their-ornamentation/. Is this not (as Bruno Hochart suggests) the Sieur De Launay, quai de Gesvres recommended by Petit de Bachaumont for his composition frames at this time?

84/85. La Tour Restout/Dumont

J.46.2687/J.46.1681. Why combine the entries? In the discussion of the Revolutionary history, XS omits the crucial note in the 1796 that the works were now “sans bordure”, the 1793 inventory having noted that, in view of the damage inflicted by the artist, “on peut compter que les glaces.” Why aren’t there sections for the œuvres en rapport? (There are many in the Dictionary, including of the full versions and the preparations.) A more consistent approach to œuvres en rapport (which are sometimes just cross-referred to the Dictionary, sometimes set out in full, sometimes embedded in the text) would make the book easier to use. Among the omissions from the bibliographie is Denk 1998, figs. 22 and 23 (her work is cited for the Chardins, but has many more pastels).

86. La Tour Lemoyne

J.46.2015. The incomplete bibliographie omits for example Denk 1998, pl. VI; McCullagh 2006, fig. 8; Williams 2015, fig. 5.5.

A far more extended discussion of which salon etc is required, including of my classification: I published the Dormeuil version as not autograph in the online Dictionary (J.46.2011) in 2013. But I think it likely that it is a copy of the lost La Tour rather than (as XS implies) a pastiche (a derived work with alterations) after the Louvre J.46.2015. There are three points XS does not discuss. First, there are differences in the face: notably the cleft chin and tighter jowls in J.46.2011 indicate that J.46.2015 does show an older figure, albeit probably not as much as 16 years older (but the pastel shown is 1763 was probably executed in the 1750s). Second, XS does not mention the Valade painting in which the head (including the wig) seems to be copied directly from J.46.2011 (or the lost autograph prototype J.46.201, quite possibly the Joly de Bammeville pastel J.46.2023). Third, an examination of Lemoyne’s workshop sale in 1778 (see http://www.pastellists.com/Collectors.htmL ) reveals that he owned other copies after La Tour pastels (the strongest hope for the Dormeuil pastel was the provenance).

87. La Tour Maurice de Saxe

J.46.2865. All the copies and more are of course in the Dictionary. XS and I disagree about status of some versions. XS discusses the Pannier version, which he regards as autograph, and mentions the Christie’s 2015 sale but does not state that it was there classified as “attribué”. XS does not disclose which pastels he has examined de visu (the Dictionary does disclose this, using the symbol σ).

For “Prohengues” read Pierre, marquis de “Prohenques”; B&W’s error has been repeated in numerous secondary sources, obscuring the identity of the maréchal de Saxe’s executor.

XS’s bibliographie omits Jeffares 2015e, fig. 11.

88. La Tour Louis XV

J.46.2089. The bibliographie omits Fumaroli 2005 and Fumaroli 2007. The presentation of the œuvres en rapport (here and in other entries) doesn’t assist in determining whether the sales refer to the same or different versions. In the discussion of the Liotard versions, the pastel in Vannes which R&L include was discovered by me in Vannes, and first published by me in the 2006 print Dictionary. The copy in the musée Garinet is in oil, not pastel. Among a number of omissions (listed in the Dictionary) is a pastel copy in La Salle University Art Museum, and the version listed (with the queen photographed) in Schloß Seifersdorf in 1904 (see further under cat. 89).

In XS’s Louvre lecture (YouTube, at 46m30s) it is stated that the frame for this and for the queen (cat. 89) were made by Maurisan, and his receipt for frames for pastels of these subjects is mentioned on p. 164 of the catalogue. But according to Pons 1987 (p. 48), only that of the queen could correspond with the works in the Louvre: the 1748 invoice covered works by La Tour and Nattier, “dont un par M. La Tour” [my emphasis]. Indeed the entremilieux of the frames for the king and dauphin were “d’un losange et entrelas et de bandes très délicatement travaillé”, which are not found on the Louvre frames. If XS has new evidence, he should give his source and explain Pons’s error.

As XS has repeated (on p. 176f) his previous discussion about the provenance of the other pastel of Louis XV now deposited in the Getty (fig. 40), it may be worth correcting this at some length. (The online version of the Dictionary was amended to follow Salmon’s 2007 Metropolitan Museum journal article, but I will shortly correct it in line with this discussion.) The pastels of Louis XV and Marie Leszczyńksa in the Delaherche sale, respectively lots 176 and 177, were described in considerable detail in the catalogue:

This makes if quite clear that they were copies of the pastels in the Louvre (the king’s ermine mantle is not present in the Getty pastel, and the frame described is a copy of that in the Louvre, quite different from that of the Getty; the queen’s frame is also evidently a copy of that in the Louvre, which differs from that of the king). These were no doubt the pastels that appeared in the Sichel sale, where they were respectively lots 32 and 31 (not 31 and 32 as in XS, p. 176);

but it was there, not in 1910, that they were separated, with the queen being bought by Perkins, while the king was acquired by Bourdariat. At this sale they were “école de La Tour”, a euphemism for copies; they were of different sizes, and had different frames. It isn’t clear if they were reunited by the comte de B… whose sale took place in 1910; it seems more likely that these were a different pair, now described as pendants, both 65×54 cm, and the attribution upgraded:

The annotation in the sale catalogue is ambiguous, but is consistent with the statement that Mannheim bought Marie Leszczyńska (as he died three weeks later it would have been back on the market very rapidly), while this version of the king was bought by the great-grandfather of the owner of the Getty pastel in 2004. But that pastel cannot have been the one in the Delaherche or Sichel sales. And that pastel copy and that of the queen, missing from the œuvres en rapport, are significant perhaps because of the trouble that had been taken to copy each of the two different frames. One speculates if they might even be among the copies recorded by Durameau in the magazin at Versailles in 1784.

89. La Tour Marie Leszczyńska

J.46.2269. The bibliographie omits Fumaroli 2007, repr.; Tarabra 2008, p. 294 repr.; Grison 2015, fig. 7; Perronneau 2017, fig. 12; Goncourt 1867, p. 350f has a passage that should not be overlooked but appears only on p. 38. See also the 1958 Times review cited above (Chardin, cat no. 42-45).

The œuvres en rapport refers to the Dictionary, but incorrectly states that I have omitted an oil copy sold at Sotheby’s Olympia, 20.iv.2004; I have not – it appears between J.46.2294 and J.46.2297 (oils don’t get J numbers but do appear in the sequence). The copy in the mBA Bordeaux (inv. 1431) is not a painting but a pastel (XS repeats Monnier’s error). The version listed in Nancy in the 1895 catalogue does not appear in the 1897 edition.

The version said to be “conservée à Berlin (ancienne collection Cassirer, vente, Londres, 23-24 mars 1926” is my J.46.2291, sold in Berlin, at the auction house Cassirer & Helbing, 23–24.iii.1926, Lot 416 from the collection of Graf Brühl – apparently the one photographed in Schloß Seifersdorf in 1904 (left). Given Brühl’s importance in the Saxon court this and its pendant, Lot 415 from the same sale (which Monnier and so XS didn’t mention), are of some interest: all the more so because the frame, which is just barely visible in the photo (and which I originally mistook for a Dresden frame), appears also to copy the Louvre frame for Marie Leszczyńska:

The version said to be “conservée à Berlin (ancienne collection Cassirer, vente, Londres, 23-24 mars 1926” is my J.46.2291, sold in Berlin, at the auction house Cassirer & Helbing, 23–24.iii.1926, Lot 416 from the collection of Graf Brühl – apparently the one photographed in Schloß Seifersdorf in 1904 (left). Given Brühl’s importance in the Saxon court this and its pendant, Lot 415 from the same sale (which Monnier and so XS didn’t mention), are of some interest: all the more so because the frame, which is just barely visible in the photo (and which I originally mistook for a Dresden frame), appears also to copy the Louvre frame for Marie Leszczyńska:

See the discussion above (cat. 88) for the Delaherche and Sichel copy: on p. 179, XS writes of the Delaherche version “il ne semble pas s’agir de la version du Louvre”: this seems to suggest he thinks it is of a different model – but the Delaherche catalogue description above follows the Louvre version precisely. We have no evidence of what the frame on Graf Brühl’s Louis looked like, but it seems quite likely that at least two sets of contemporary copies of the La Tour pastels were issued with the frames as well as the pastels being copied.

Among the oeuvres en rapport, XS lists a copy of the La Tour by Tocqué at Gatchina. This again is taken from Monnier without identifying her mistake. She cited Serge Ernst, Gazette des beaux-arts, April 1928, p. 244, where the Gatchina painting is stated to be after the large painting in the Louvre: but this of course is after Tocqué’s own painting in the Louvre, inv. 8177, sd 1740, and commenced 1738 (ten years before the La Tour), as comte Doria pointed out in the Gazette des beaux-arts just a few months later (September 1928, p. 156). Gillet 1929 reproduces the Tocqué and La Tour on facing pages (8/9).

La Tour, tête de Marie-Josèphe de Saxe, inv. 27618 bis

J.46.22251. The recently discovered first attempt at a portrait of Marie-Josèphe de Saxe (as the paper size indicates, surely an abandoned work rather than a préparation) is mentioned and reproduced in two places (p. 179, fig. 41 and pp. 198ff, fig. 55). This has perhaps distracted attention from the chronological problem it raises, which isn’t adequately dealt with by XS’s statement “On ne sait si ce fut La Tour qui utilisa lui-même sa préparation pour doubler son carton ou si cette opération eut lieu postérieurement.” The problem is that XS relates the unfinished head to the 1761 portrait of the dauphine, while he also considers that the pastel of the queen was that exhibited in 1748. It is scarcely likely that a completed pastel, exhibited at the Salon and delivered to the royal collection, would be returned to the artist’s studio a dozen years later to have a new backing fitted.

The problem seems insoluble, but thanks to two discoveries Ólafur Þorvaldsson has been able to propose an ingenious solution. Although at first sight the unfinished head (fig. 55) appears to match closely cat. no. 94 (and indeed the related preparation fig. 54, as well as the large Saint-Quentin LT 17), you might think that it looks a little younger, before dismissing that as a subjective and unreliable judgement. But there is a crucial (and objective) difference in the hair on the left side of her head. In the 1761 work this is swept back in a series of curls which are all concave up: in the unfinished head, however, they are concave down, indicating a series of tighter, smaller curls from a previous era. The discoveries are of two miniatures which share this feature, one in the Habsburg collection in the Miniaturenkabinett at the Hofburg, which is somewhat perfunctory (and hitherto misidentified), but the other, in the Wallace Collection (set in a later box), gives us I think a pretty clear idea of what La Tour’s very first pastel of the dauphine must have been like:

The miniature is in Reynolds 1980, no. 30 repr., as anonymous, but recognised by Guy Kuraszewski of Versailles (letter of 1975 in Wallace Collection archives) as of Marie-Josèphe de Saxe at the time of her marriage in 1747. It is evidently after the lost La Tour, and shows the dauphine in almost exactly the same pose as the 1761 pastel, ignoring the 1749 composition entirely. Commissioned in 1747, and finished by the following year (as XS notes, p. 198), it must have been in La Tour’s studio at the same time as he was preparing the pastel of the queen (cat. no. 89) for exhibition at the salon.

90. La Tour Mme de Pompadour

J.46.2541. I have numerous additions to the inevitably incomplete bibliographie, ranging from Gautier 1858 to Guichard 2015. It was reproduced as early as 1851. By 1890, when an American called Hamilton McKay Twombley thought he had bought the original for $2250, Alfred Trumble, editor of The collector, discussed the swindle in several articles, pointing out that copies were available for as little as 1000 francs. The copy XS says I have omitted is in fact there (J.46.2568), and has been since before the sale (20 October 2017), but no doubt there are many others out there. XS erroneously states that it was engraved by Jean Massard (1740–1822); this is a confusion with the steel engraving of 1838 by Léopold Massard (1812–1889).

It is surely of interest to cite Mantz (1854, p. 177), writing just 100 years after its completion, describing the work as “un de ceux que le temps a effacés.” Less accurate is Champney 1891, who thought “the head cut out during the Revolution”. The omission of Professor Goodman’s monograph on The portraits of Madame de Pompadour (2000) is odd. Champfleury 1855 prints in full (before adding to it) the full two pages of Sainte-Beuve’s famous discussion, from Monday, 16 September 1850 (the citation in XS is the first page only in the 5th edition of the collected Causeries), but it was Arsène Houssaye who first wrote extravagantly about the pastel (1849), and probably inspired Saint-Beuve.

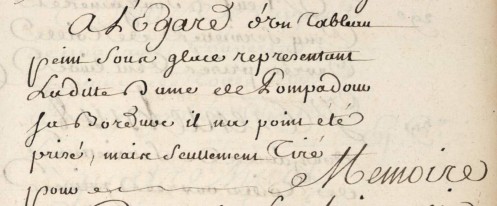

The most significant omission however is the correspondence of Mme de Graffigny, specifically her letter of 8.vii.1748. Even if we believe La Tour’s claim to have destroyed the first version of the portrait, it is perfectly clear that XS’s account (“La première mention du portrait date de 1752”, p. 184) is far too late.

A general problem is the treatment of salon critiques, which are not explicitly listed in the bibliographies. Several are discussed in the main essay, but there is no reference for example to the Gautier-Dagoty Observations… (1755), which is omitted from all standard bibliographies until I published it online in 2015 (you can find the full text in my exhibitions). It contains important observations on the significance of the original glass which had to be removed at some stage after 1942. The standard spelling (p. 184) of synérèse (synaeresis) is with an initial s, not a c (as the etymology requires). Guiffrey 1873 reproduced accounts for the workmen and carpenters employed to relocate the pastel overnight during the Salon of 1755 due to the reflections in the glass exacerbated by its initial position.

Also omitted is the discussion of the portrait in two letters by Prinz Wilhelm von Preußen to the marquis de Valori, 23.xii.1755, 17.i.1756; these relate both to the perceived likeness of the work and to the role of the image as a diplomatic tool (Wilhelm being offered an unrecorded copy).