Duveen’s pastels

Everyone reading this will know of the art dealers Duveen Brothers, probably because of their association with the famous expert Bernard Berenson and the much discussed conflicts of interest arising from their relationship. Plenty of books have followed, so there is no need for me to say more. And some of you will be aware that the firm’s records are available online, at the Getty Research Institute’s portal. They’ve been available since 2007, but it’s fair to say that the sheer volume of material makes these files rather hard to use, and accordingly I suspect they have not yielded all their gems.

Everyone reading this will know of the art dealers Duveen Brothers, probably because of their association with the famous expert Bernard Berenson and the much discussed conflicts of interest arising from their relationship. Plenty of books have followed, so there is no need for me to say more. And some of you will be aware that the firm’s records are available online, at the Getty Research Institute’s portal. They’ve been available since 2007, but it’s fair to say that the sheer volume of material makes these files rather hard to use, and accordingly I suspect they have not yielded all their gems.

Browsing through the archives one cannot escape some reflections on the nature of the business. First, particularly in the early years, pictures were only a tiny part of what was a general antiques and decorators’ business. The stock books (the best place to start) have everything from rolls of fabric and slabs of marble to miniatures and even a Michelangelo sculpture (though at a price that suggests otherwise). There are Romneys more valued than Rembrandts, and knick-knacks the inadequacies of whose description disables cynicism. Of course when one of the magic names can be claimed, it will be: clients want to know whether it’s a Reynolds or a Gainsborough, not whether it’s a great example by a lesser name: it has always been thus. So the eighteenth-century portraitists admitted into the fold included also Hoppner, Nattier and Vigée Le Brun – but remarkably few others. However in amongst the tens of thousands of objects there are some great masterpieces, and even a few significant pastels. It is the latter that I want to note here. Among pastellists, the roll call is short – and slightly surprising: the inevitable Rosalba (but sold in pairs with nothing to identify them); the newly saleable Daniel Gardner; lots of John Russell; four “Perronneaus” and even some Coypels (of these more below) – but oddly no La Tour. Liotard of course was unknown then, at least in the furniture trade.

The business model seems to be very client-focused: the traditional trope of the wealthy but ignorant American (of course there were exceptions) to be fed by a vast quantity of items sent on approval. The accountancy practices might raise some eyebrows, as many of these transactions are recorded as firm sales when the items return soon after (for the same price) and receive new stock numbers. The huge range of items surely meant that the firm could not have been expert in all these fields – an impression reinforced by the amount of trade between dealers and intermediaries. Most depressing of all are the summary descriptions of so many items – “2 small oval pastels of ladies” and so on, which even I can’t usefully record in the Dictionary.

Another unusual feature from a modern perspective is the absence of catalogued exhibitions. An exception was an exhibition of “ten pastel drawings by John Russell, RA”, the (unillustrated) catalogue for which bears no date, but must have been about 1911, since an additional item at the end was Gardner’s Sir John Taylor, which the firm bought and sold that year. One of the Russells is the magnificent Mrs Jeans now in the Louvre (J.64.1863) and which I blogged about before (and here); I had worked out then that it had been sold c.1910, but I didn’t know to whom. Duveen sold it on within the trade; it was the firm Jacques Seligmann that sold the pastel (in 1919) to Mme Démogé (she eventually gave it to the Louvre). Among the other “Russells” in that show were three which corresponded to pictures Williamson 1894 had catalogued as lost. (We know the firm had a copy of Williamson, as it was meticulously recorded in the London stock book, purchased in February 1901 from Sotheran’s for £4/10/-.) The Duveen versions have been lost again, so it isn’t possible to form a useful view as to whether they were tempted to borrow the names to decorate anonymous works, just as spies are said to adopt the identities of dead infants.

Another unusual feature from a modern perspective is the absence of catalogued exhibitions. An exception was an exhibition of “ten pastel drawings by John Russell, RA”, the (unillustrated) catalogue for which bears no date, but must have been about 1911, since an additional item at the end was Gardner’s Sir John Taylor, which the firm bought and sold that year. One of the Russells is the magnificent Mrs Jeans now in the Louvre (J.64.1863) and which I blogged about before (and here); I had worked out then that it had been sold c.1910, but I didn’t know to whom. Duveen sold it on within the trade; it was the firm Jacques Seligmann that sold the pastel (in 1919) to Mme Démogé (she eventually gave it to the Louvre). Among the other “Russells” in that show were three which corresponded to pictures Williamson 1894 had catalogued as lost. (We know the firm had a copy of Williamson, as it was meticulously recorded in the London stock book, purchased in February 1901 from Sotheran’s for £4/10/-.) The Duveen versions have been lost again, so it isn’t possible to form a useful view as to whether they were tempted to borrow the names to decorate anonymous works, just as spies are said to adopt the identities of dead infants.

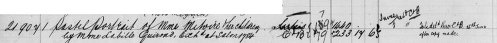

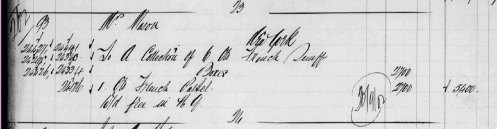

An insight into the firm’s practices can be seen in this entry, for the rather wonderful Labille-Guiard pastel exhibited in 1783, Mme Mitoire et ses enfants (J.44.221), shown here in its splendid frame. What the invoice shows is that the purchase (from Kraemer frères, recorded in July 1901) was sold on “after copy made”. That work is surely the pastel I catalogue as a copy (J.44.224) on appearance only; it has been sold repeatedly, between 1919 and 2018, as autograph, and appears in Mme Passez’s catalogue raisonné as such (no. 44):

An insight into the firm’s practices can be seen in this entry, for the rather wonderful Labille-Guiard pastel exhibited in 1783, Mme Mitoire et ses enfants (J.44.221), shown here in its splendid frame. What the invoice shows is that the purchase (from Kraemer frères, recorded in July 1901) was sold on “after copy made”. That work is surely the pastel I catalogue as a copy (J.44.224) on appearance only; it has been sold repeatedly, between 1919 and 2018, as autograph, and appears in Mme Passez’s catalogue raisonné as such (no. 44):

Another example is the Gardner pastel of an unknown Lady holding a mask of Comedy, now in the Abbot Hall Art Gallery (my J.338.1901). This was purchased for £500 in 1906 from a Mr Fulcher, but Duveen also paid 30 guineas (to Vicars Brothers, another dealer in Bond Street) to have a copy made to “give” to the vendor. Recorded without identity in the 1906 stock book, the following year it is annotated as “Miss Ross of Cromarty”: a somewhat improbable suggestion as the Ross of Cromarty at the time had a (deceased) son but no daughter.

Another example is the Gardner pastel of an unknown Lady holding a mask of Comedy, now in the Abbot Hall Art Gallery (my J.338.1901). This was purchased for £500 in 1906 from a Mr Fulcher, but Duveen also paid 30 guineas (to Vicars Brothers, another dealer in Bond Street) to have a copy made to “give” to the vendor. Recorded without identity in the 1906 stock book, the following year it is annotated as “Miss Ross of Cromarty”: a somewhat improbable suggestion as the Ross of Cromarty at the time had a (deceased) son but no daughter.

A good set of Rosalba’s Four Seasons was purchased in 1901 from the celebrated antiquaire Mme Lelong in Paris. (They could well be the protoypes for the set of copies now in Bergen op Zoom, Markiezenhof.) They were divided – the records are confusing as to which seasons were in which – with two being sold almost immediately to the Duke of Marlborough for a generous mark-up (£4750, against £700 allocated cost). The stock book indicates that “Mr Joe says write off 1/2”. The Duke sent his two back the following year. Either they or the other two were sent then to George Jay Gould in Lakewood before again being returned; Duveen sold them to Lucius Peyton Green and his wife in Los Angeles. One of them is now in the Huntington Library (J.21.1353), the others lost. Other pastels in public collections for which this research has uncovered hitherto unknown provenances include the Coypel marquise de Lamure (J.2472.174) in the Worcester Art Museum and those mentioned below.

But most surprising perhaps is the number of Perronneau pastels that can be found in the books. One of them, Mme Le Boucher de Richemont (J.582.1518), is uncontroversial – setting aside the minute point that the inscription the Duveen stock book records (in translation), “peinte en mars 1770, âgée de 42 ans et 7 mois”, implies she was born in 1727, not 1728; and I can add now that she died in 1797 – but apart from that everything is correct in the recent Dictionary entries, up to the 2015 sale when it sold for $5000 (or $6250 with costs). Duveen bought it at the Cronier sale in 1905 for 10,600 francs (£469 then, about £50,000 today adjusted for RPI inflation), and sold it four years later for 11,710 francs (to Alphonse Kann).

You will all recognise the famous National Gallery “Perronneau” (inv. NG 3588; my J.582.189) at the head of this article, given by Sir Joseph Duveen to the nation in 1921. I have previously said that too much has already been written about this wretched pastel which I and many others regard as “wrong”. I had rather hoped that Humphrey Wine’s new National Gallery catalogue would finally complete the story and spare me the need to mention it again. But while I commend the essay on this picture to you, there are some critical gaps in the story which I think worth filling in. I don’t just mean the omission of references in the literature (although I should not have missed out Florence Ingersoll-Smouse in La Revue de l’art ancien et moderne, xli, 1922, repr. p. 401, where it is described as “le plus séduisant portrait d’enfant de Perronneau…le chat merveilleusement rendu”), nor the fact that Charles Ricketts’s letter to “a certain Brown” was to Eric Brown, director of the National Gallery of Canada. And here I pass over the technical discussion.

Rather I want to deal with Wine’s footnotes 3 and 4 on his p. 396 which are founded on the idea that “there is no certain reference to NG 3588 in the Duveen Brothers records.” Indeed his provenance shows no event between the purchase from Lady Dorothy at an uncertain date to the donation to the NG in 1921. He explores instead the reference which he did find in the records to “2 pastels by Perronneau of the same lady in different positions” bought from Lady Dorothy Nevill in December 1902 for £366/7/7 and sold to Sir Joseph in 1908, cautiously concluding that the discrepancies in the description preclude certain identification of either with NG 2588.

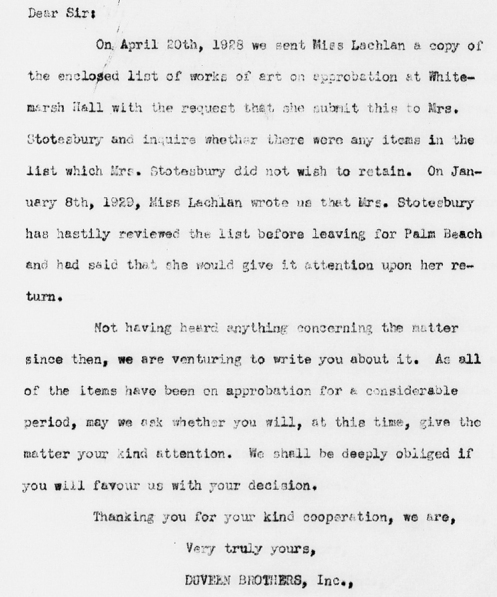

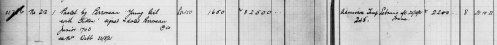

In fact those two “Perronneaus” are the works supplied by Duveen to Edward Stotesbury in Philadelphia. They were sent on approval in 1922, but not paid for until 1930 (for $15,000) after a letter chasing payment (the invoice listing “A pair of Old French Pastels. Portraits of Ladies by PERRONNEAU” in Mrs Stotesbury’s boudoir):

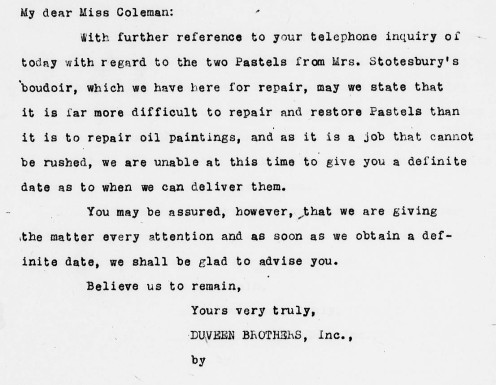

Unfortunately many clients were unable to provide pastels with a museum-standard environment. By 19 March 1930 the housekeeper at Whitemarsh Hall sent them back to Duveen Brothers to be “put in first class condition” before the Stotesburys returned, on1 April: they were not ready by then, as Duveen explained to the staff:

They depict one of Lady Dorothy’s ancestors, Mrs Thomas Walpole, née Elizabeth Van Neck. The pendants have since been split up, and their attributions confused and identities lost: in the 1944 Stotesbury sale, a pastel by Valade took on the name of Elizabeth Van Neck, the Perronneaus now unidentified. One (which you won’t find in Arnoult 2014 – it is J.582.1798), anonymous French school in 1944, sold last year as anonymous British school for $1250, a tiny fraction of the price Stotesbury paid, although its present condition is poor and it has lost the magnificent frame in which Duveen’s photograph showed it.

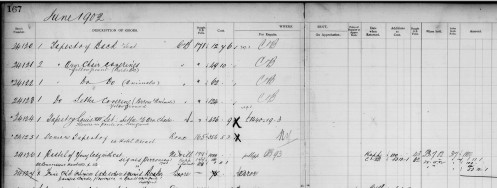

But returning to NG 3588, there is indeed not one, but numerous certain references to be found in the Duveen archive if you have the patience. Easiest to find is the image among the album of 40 photographs of pictures from the French school, which I show above. Of course the pastel is known from many reproductions, going back to the colour plate accompanying Lady Dorothy’s article about her own collection published in The Connoisseur in February 1902. Wine thought its reuse in 1909 might indicate the date when Duveen acquired the pastel. In fact Duveen bought it much earlier – just a few months after Lady Dorothy’s article appeared. And the circumstances are (almost) exactly as Edward Fowles relates in his 1976 memorandum (as you will find in Wine), writing about events that occurred 74 years before – when he, as the 17-year-old office boy, was sent to the bank to collect £1000 in gold sovereigns for the quaint old lady. That £1000 cost is indeed what we see from the London stock book entry:

What we also see, and which perhaps as office boy Fowles didn’t know, was that a 10% commission was payable to one “Kopp”. I think Fowles would have mentioned this if he knew, because much later in his memoir he has a wonderful story about this confidence trickster. Gottfried Kopp, of humble origins, reinvented himself as Godfrey von Kopp, an Austrian aristocrat, setting up an art dealing business in Rome, Paris and London, in the course of which he “sold” the original Arch of Constantine to one American tycoon, and Trajan’s Column to another. Needless to say the transactions involved advance fees, and delivery did not follow. In 1905 bankruptcy proceedings were commenced against him in London, and he was not heard of again.

In any case Duveen had acquired his “Perronneau”, for the not insignificant sum of £1100 (multiply by at least 100 for RPI inflation, any larger number you like for purchasing power equivalence). The business depended on cashflow as much as profit, and as you can follow from the books it was sold almost immediately to one of Duveen’s American clients, Mrs Mason. You need to consult the sales ledger to find the price (and Perronneau’s name doesn’t appear there, but the stock numbers are unambiguous): £2700.

This was Mrs T. Henry Mason, née Emma Jane Powley (1850–1918), previously Mrs Lewis; her second husband, whom she married in 1899, was a mining tycoon who died in 1902. She lived in New York, Paris and London. She had form in the return stakes. In May 1906 Duveen sold her the magnificent Coypel of the Jullienne couple now in the Met (J.2472.171); she returned it in August. Duveen records also note other pastels sold to her, as well as a disturbingly high invoice of $1042.10 for “restoring three pastels”. Correspondence after her death indicates that one of the Russells Duveen had bought back from her (Mrs Meyrick, described as “very fine” when original despatched to her in July 1901) was in such poor condition that it could be sold for decorative purposes only.

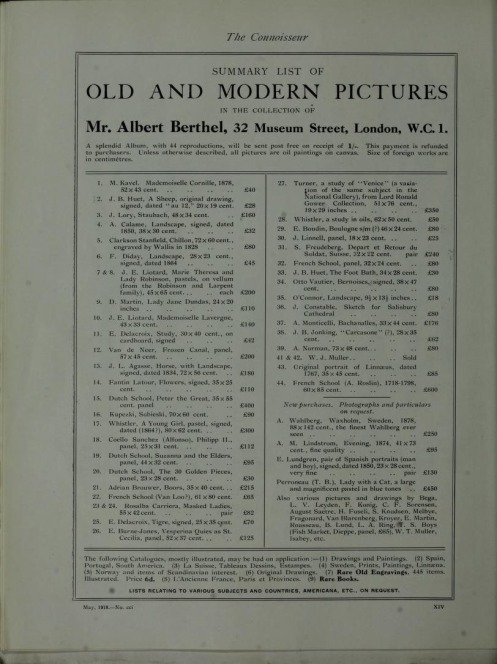

In any case, NG 3588 came back to London, although not necessarily to Duveen Brothers itself. It may be that Sir Joseph privately tried to market it through other channels. It seems highly likely that this was the “Lady with a cat, a large and magnificent pastel in blue tones”, advertised by the dealer Albert Berthel, 32 Museum Street, London, in The Connoisseur, May 1918, p. xiv, for the price of £450 (a more realistic level, perhaps suggesting that Duveen had found it difficult to shift – unless of course it was simply a copy):

Fairly soon after, another Duveen client received NG 3588: one “Mrs Webb”. Duveen had two clients of this name: one was Mary Welsh Randolph, Mrs Francis Egerton Webb (1868–1962) of 405 Park Ave, but I suspect this was Electra Havemeyer, Mrs James Watson Webb (1888–1960), collector and founder of the Shelburne Museum. Perhaps Duveen had not noticed that Mrs Webb’s tastes had changed, and instead of the French dix-huitième, she was now focused on simple New England folk art. In any case, once again the work came back, in August 1921, the refund of £1650 no doubt representing the price Mrs Webb had been invoiced.

By this stage Duveen had had enough. He ordered a rather splendid (if opulently proportioned) Louis XV reproduction frame from Cadres Lebrun (the firm still exists but Mme Fouquin Lebrun has kindly informed me that their archives only go back to 1931) for 2200 francs (about £44, say £4400 today) in time to present the pastel to the National Gallery.

Postscript (19 December):

Ólafur Þorvaldsson has kindly drawn my attention to a second image in the Duveen archive, showing NG 3588 in the frame it had before Cadres Lebrun came to the rescue:

Dear Neil,

I hope this finds you well. This is just to send much retarded thanks for your December study on Duveen’s pastels with so many new, painstakingly established details which I read with habitual fascination which all your studies command.

Nothing new in pastels that I know of. The Dresden Liotard exhibition, which I was not able to see, has closed, what remains is the fine catalogue.

About as different as possible from the Edinburgh-London exhibition, the program of the Dresden venture proved worthwhile. Art can go in so many directions, expcted and unexpected ones. With my best regards Marcel

________________________________

I shall treasure the memory of our study day in Dresden, a year ago; such a magical gallery