We are told (often enough to believe it) that what you read on the internet cannot be relied upon, while what is printed in books can. We should know better; and sometimes we get to find out which printed authors are unreliable. Thus the standard book on Daniel Gardner (1921) by G. C. Williamson (who wrote so many monographs that suspicions of his thoroughness must have occurred to the most gullible) tells us that Gardner’s marriage took place in 1776 when in fact it was two years earlier; and that he bought his colours mostly from Roberson and Miller (a firm only recorded from 1828 in the NPG database of British artists’ suppliers). Perhaps these minor instances prepare us for the fact that although he prints “Dr” before his name on the title pages of this, and many other of his books, Williamson held no such degree.

We are told (often enough to believe it) that what you read on the internet cannot be relied upon, while what is printed in books can. We should know better; and sometimes we get to find out which printed authors are unreliable. Thus the standard book on Daniel Gardner (1921) by G. C. Williamson (who wrote so many monographs that suspicions of his thoroughness must have occurred to the most gullible) tells us that Gardner’s marriage took place in 1776 when in fact it was two years earlier; and that he bought his colours mostly from Roberson and Miller (a firm only recorded from 1828 in the NPG database of British artists’ suppliers). Perhaps these minor instances prepare us for the fact that although he prints “Dr” before his name on the title pages of this, and many other of his books, Williamson held no such degree.

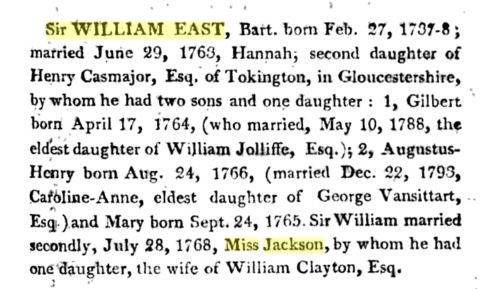

But we assume this cannot occur with reputable works of reference, such as the Betham’s Baronetage of 1803, which prints the following for Sir William East, the subject of a family piece by Gardner (above) which was not known to Williamson at all:

And you will find the same in New Baronetage of 1804:

followed in Collins, Burke and all the other standard genealogies since. (You may recall that the Baronetage was Sir Walter Elliot’s favourite book.) So when we come to Daniel Gardner’s wonderful East family, we have a problem. The pastel, which is in a private collection (I am most grateful to the owners for letting me reproduce it), was last seen in public in 1980, when the Burlington Magazine justly described it as “remarkably ambitious”. It is indeed one of Gardner’s happiest works: its combination of vibrant colouring, clever, geometrical composition and social interest in the sitters’ activities convey a joie de vivre rarely found in the portraiture of the day. It is also remarkably early in Gardner’s career (aged 24). The owners have delightfully found a couple of examples of Sir William’s amateur painting (miniatures of two of the children) of which there was otherwise no trace (apart from an entry in his wife’s diary, noting “Sr Wm begun to paint Abelard” as his first action after recovery from illness: did he base this on Gardner’s own gouache, engraved by Watson in 1776?). All this demonstrated a concreteness to Gardner’s imaginative choice of accessories. So too does the garden urn, which I think is no longer to be found at Hall Place, now taken over by an agricultural college, much of the gardens having now been built over: but happily a photograph from an old issue of Country Life shows the same piece:

Gardner’s arabesque was made in 1774, but there is no easy reconciliation of the dates and ages of the children with the Baronetage. The girl’s age is clearly between her brothers, and if she is the legitimate daughter of the second Lady East (and the daughter who married Sir William Clayton less than 17 years after her own parents’ marriage) the discrepancy is beyond the limitations of Gardner’s representational skills or any tolerable level of flattery.

While delving into this I came across a Ph.D. thesis online, The effect on family life during the late Georgian period of indisposition, medication, treatments and the resultant outcomes, where some of Lady East’s diaries are discussed – in the context of her husband’s frequent indispositions from gout (perhaps that should not surprise us: his father had made his fortune as commissioner for wine licences under George I). The diaries examined are the volume (numbered 4 on the cover) dealing with 1791–92, in the Berkshire Record Office, and one covering 1801–3, in a private collection, with 14 on the cover. Dr James had earlier published a paper in which he thought that the Lady East who wrote the diary was Hannah Casamajor; but unfortunately, no doubt having consulted the standard genealogies (was this a supervisory intervention?) the author “corrected” the thesis, resulting in a thorough confusion of the two ladies. He still gives Miss Jackson’s forename as Hannah, and her year of birth, 1742, is the same as Hannah Casamajor’s: so this looks more like confusion than coincidence. He also mentions the Gentleman’s Magazine entry in 1768 announcing the marriage of Sir William with “Miss Jackson, of Downing Street”, which seems to be the evidence of the second marriage (with the date 28 July 1768), although of course it is now in all the standard genealogies from Betham on.

This is all somewhat mysterious, the more so since on checking the Gentleman’s Magazine for that year, the reference is actually to “Sir William Best”:

Now that may well be a misprint (I can’t locate a Sir William Best, Bt of marriageable age at that date). Nor indeed is there an obvious family of Jacksons in Downing Street at the time, but that is less curious. But combine that with the awkward dates about the second Mary who married Sir William Clayton very young and one wonders what is going on.

One plausible explanation is that Sir William East had a liaison with Miss Jackson before their marriage. The absence of records of births often points to such irregularities.

But the Ph.D. thesis also tells us Lady East refers to Harriet Casamajor as her sister – although it also correctly notes that such terms were often used fairly broadly in the 18th century.

I turned then to Sir William East’s own will. It’s an extremely long document, and doesn’t seem explicitly to mention the Gardner (but I wouldn’t expect it to). In it I found references only to one “late dear wife”, and I also found the following:

I give to Harriet Casamajor sister of my late dear wife any two of the pictures painted by myself which she shall select out of my whole set…

…to the before mentioned Harriet Casamajor for the great kindness and unwearied attention to me and to her sister my late dear wife for upwards of forty years during her and my illness the sum of five thousand pounds in addition to what I have hereinafter bequeathed to her.

There are also smaller bequests to two of Lady East’s sisters, Maria Clemenza widow of the late Reverend Mr Bryan and Elizabeth widow of Robert Goodwin: both these turn out to be Casamajor sisters. You can see my Casamajor genealogy here; remember also that Gardner painted Hannah’s relative Mrs Justinian Casamajor and eight of her twenty-two children in a pastel now in the Yale Center for British Art:

There is also a passage relating to the marriage settlement with his wife and in consequence of her death during Sir William’s lifetime provisions for the income from the funds to be paid to his daughter Mary, Lady Clayton.

So I searched diligently for the marriage of any William with a Miss Jackson on 28 July 1768 in parish registers. And I found (and attach) the one which must be the cause of the whole confusion. Plain William Bess [sic] married Elizabeth Jackson on that day in St Margaret’s Westminster (she is “of this parish” – and it is where Downing Street is located).

All of this demonstrates that there was no second marriage to a Miss Jackson (at least not for Sir William East), and that Hannah Casamajor was the only Lady East, dying in 1810 after the long illness discussed in the diary and referred to in the will. And so only one Mary too. We simply find it so hard to imagine that Burke and Debrett are wrong, but they are, from time to time. Here is the correct East genealogy; I trust Sir Walter will annotate his copy accordingly.

I have now managed to track down an earlier volume in the sequence of Lady East’s diaries, which is now in the Lewis Walpole Library whose staff have most generously provided me with access to it. Numbered 2 on the cover, this volume covers the period from 1776 to 1785 (presumably No. 1 covers the date of the pastel, but is sadly still missing). Their account of its contents, which has now been corrected, previously catalogued the author of the diary as the former Miss Jackson. There are indeed copious references not just to Hannah’s sister Harriet, but a number of other siblings in terms which put her identity beyond doubt.

For the most part the diary is of mainly domestic significance and its content factual (if not matter-of-factual) rather than discursive. As with the volumes analysed by Dr James, health is a major consideration: Lady East’s concern for her husband’s gout is amply demonstrated, as with the later volumes, consistent with Benjamin Franklin’s rather antiquated “Rules & maxims for promoting matrimonial happiness” which have been painstakingly copied out in full (presumably from the reprint in the Lady’s Magazine for 1770). The document also contains a full transcription (I think from the London Magazine for 1767) of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s refutation of La Rochefoucauld’s cynical maxim, “That Marriage is sometimes convenient, but never delightful.” The overwhelming impression from the pages of diary 2 is one of a happy marriage, and even when noting Sir William’s long walks with Lady East’s sister, there is plainly no inkling of the conspiracy between Sir William and Harriet to control and disempower Lady East as develops in the later volumes analysed by Dr James and reinforced by the terms of his will: Sir William every bit the Bad Baronet of a Gothic novel. Perhaps further volumes of Lady East’s diary will emerge to complete the narrative (or is this a challenge for a new Wilkie Collins?).

Apart from medicine and marriage, the document mainly concerns the round of social visits at Hall Place following the sale (by Mr Christie) of the house in Leicester Fields; their subsequent visits to London include staying in lodgings in Bond Street they dislike enough to move from immediately. But the lure of sights such as Mr Lunardi’s balloon at the Pantheon cannot be ignored, even if Mrs Casamajor’s lateness at breakfast meant that they missed the start of Blanchard’s ascent a few days later. Back home in Hall Place, precipitation is recorded with frequency, if not meteorological precision; much tea is drunk, and the odd ball is held (arriving home at 6 am after one of these). The London theatre plays a big role: they see Henderson as Falstaff, and return a few days late to see him in Hamlet, supping with him afterwards. Mrs Siddons is noted, while Mrs Wells imitates her to perfection. Back in Berkshire, it is amateur dramatics: Lady East “acted Jane Shore to the common people”, with five subsequent performances over the next days to various social groups: the shopkeepers, some servants and the neighbours.

If all this conjures up the world of Jane Austen, that may not be so surprising – the elder son, Gilbert East, was sent to board with Jane’s father, the Rev. George Austen: so we know quite a lot about the boy’s dislike of Latin and preference for dancing (perhaps that is already evident in the Gardner, where the boy’s feet take up a classic fourth position pose), and that Sir William was sufficiently grateful for the Austens’ care of his heir that he presented the tutor with a portrait of himself (was it too by Gardner, or could it have been a self-portrait?; we do not know, although, according to her letter to Cassandra of 3 January 1801, it was to be given to Jane’s eldest brother James when the family left Steventon for Bath; but it is not mentioned in James’s will).

The diary has plenty of material for the social historian about the servants. Several times in diary 2 the arrival of new liveries was recorded. We learn that a new butler was engaged, one William Lambert, at £30 per annum. The housekeeper’s wages were £20. The cook and the coachman got married. Some of others are mentioned – a postillion received a mere £5 10s. a year. The job was not without risk: one fell while accompanying their carriage, and broke his spine. When he died some months later, Lady East recorded the misfortune – along with a more detailed account of the latest episode of Sir William’s gout.

This brings us to the sixth person in the pastel: the black servant in the background, wearing the smart black and red livery with silver lace. The family were able to tell me only that his name was York, and that he arrived in Hall Place in 1767 and died in 1783. Indeed Lady East’s diary does have these entries:

Thu 8th May 1783. York, the Black Servant died in the might or rather morning at two o’clock of a consumption

Sun 11th. York bury’d at Hurly in the afternoon

But while I was reviewing the entries in the parish records for Hurley, Berkshire (which are in fact complete for the East family), I found three entries for the surname “York”: they are for the baptism of a “Fitz-William York” on 6 April 1782; of a daughter, Mary Anne York on 19 June 1783, the parents being Fitz-William York and Elizabeth York; and, just a month later, on 13 July 1783, a “John York or Hancock” with the parents Fitz-William York and Elizabeth Hancock. These entries are, to say the least, curious. While “Fitzwilliam” is most memorably the Christian name of Jane Austen’s Mr Darcy, its appearance here suggests not so much the inheritance of a vast estate but the euphemism for illegitimacy consistent with the presumably adult baptism preparatory to the registration of two irregular births which were presumably not of twins as they were a month apart. Pure speculation of course, for now at least.

Michael Gove’s vision of an Albanian future for Britain outside the EU was described in a tweet by Jacob Rees-Mogg as “eloquent”. Hardly in the category of Patrick Pearse’s graveside oration, but a good enough indicator that this battle will be fought not on Gradgrindian facts or the economy, but on the far more dangerous territory of emotional fears and concerns. So an idea so daft that only a Blackadder scriptwriter would be equipped to find a suitable description has, because of primal xenophobia, a material (if as I hope still remote) chance of throwing this country into the wilderness that (a large part of) Ireland chose a century ago, and from which it has never emerged. And against it the (not quite so large part of the) Government of this country has sought to counter this vision with Osborne’s own dodgy dossier, in which the spurious algebra is no more convincing than Euler’s humiliation of Diderot over another rather tricky issue.

Everyone here is looking foolish, most especially David Cameron for miscalculating the UKIP risk and calling for the referendum at all. There are good reasons why our form of democracy does not often resort to this device: Boaty McBoatface tells you why. (For a more serious demonstration, look at the ballot paper for the London mayoral election: what choice do voters really have if you don’t think bicycles are safe or that public money should be wasted on garden bridges?)

Cameron’s second blunder was in allowing his MPs to make individual decisions. It may have been an inevitable consequence of his first, but for me the astonishing thing is the number of Tories who have allowed ideology to triumph over common sense. And it is that chilling prospect (and the no more enticing one offered by the loony left opposition) which is the real reason to support the EU just as we have it, with all its muddles, inefficiencies and confusions. Those are our best defence against extremism and ideology. The EU could and should be our best weapon for tackling multinational tax avoidance and for regulating obscene levels of executive pay; but even where it fails, its very incoherence, its innate contradictions, its point de zèle offer by far the better outlook for a quite nice, not terribly important country to muddle through as best we can.

Let us congratulate the Scottish National Portrait Gallery on its recent purchase of the Allan Ramsay painting of Bonnie Prince Charlie – and Bendor Grosvenor, who recently identified it in his television programme: for an account of this see his blog. In his 2008 article in the British Art Journal, Grosvenor finally sorted out a long-standing confusion between the two pastels by Maurice-Quentin de La Tour of Bonnie Prince Charlie and his brother Henry, Cardinal–Duke of York, and it is these images that relate to what I want to discuss here. I shall refer to the sitters as Charles and Henry rather than as Charles III or Henry IX (or in the Stuart vocabulary of the time the Prince (of Wales) and Duke (of York)), but Grosvenor’s re-identification of the SNPG’s (slightly less) recently acquired pastel of the former as the latter raised a controversy almost as heated as British regnal numbering. The fact is that both brothers looked like one another (despite the difference in age) to within a tolerance below the inaccuracies of eighteenth century portraiture, and the identification requires evidence, not perceived resemblance.

La Tour, Henry, Duke of York (Edinburgh, SNPG)

The National Galleries of Scotland have now conceded the point, and the pastel appears on their website as of Henry (James’s “youngest” [sic] son). There is no need for me to repeat the careful and detailed arguments in the 2008 article; in the response by Edward Corp the following year (link for those with JSTOR subscriptions); or indeed in the original Corp article in the Burlington Magazine in 1997. There are also well known Stuart iconographies, among them Nicholas 1973, Sharp 1996, Nicholson 2002 to which I refer below (full details in my bibliography). Further there is a relevant, if very brief, footnote on pp. 312f of Laurence Bongie’s 1986 excellent study of Prince Charles in France (on which see also my article on Mlle Ferrand). But even a bibliography of Jacobite iconography is too vast a subject for this post.

I need only remind you that the SNPG pastel of Prince Henry was exhibited in the Salon of 1747 (among the “Plusieurs portraits au Pastel, sous le même No [111]”, although “Monsieur le Duc d’Yorck” was identified by the critic abbé Le Blanc). This itself is a little curious, because the pastel shows the prince in military guise, although Henry had already (25 May 1747, three months before the Salon opened) reached Rome having decided to abandon such a role in favour of the Church: he was created a cardinal weeks later. It was likely to have been made after Henry’s arrival in Paris, shortly after the victory at Prestonpans in September 1745, while he was trying to raise support for the Jacobite rebellion, but before his departure for Boulogne in December that year.

A pastel of Charles was exhibited in 1748 but is now lost:

(Charles was called prince Edouard in France because they already had a prince Charles – de Lorraine.) The numerous copies show that the portrait must have been extremely similar to the earlier pastel, with which it has been repeatedly confused (it does however seem that all the contemporary copies relate to the portrait of Charles rather than his brother). Its timing too was curious: when the salon opened, Charles was to be expelled from France under the terms of the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (although not signed until 19 October 1748, its terms were already known). One minor curiosity is that both pastels are reminiscent of La Tour’s portraits of Louis XV: that of Henry, with the raised arm reminiscent of Rigaud, closer to the 1745 pastel of the king, while Charles follows the more conventional pose of the 1748 pastel – the parallel with which would not have escaped visitors to the salon, or those who looked at the livret (the progression of type, from all caps for the king, to cap and small cap for his queen and heir, to cap and lower case for the foreigner was not however accidental).

Apart from Charles, all of these portraits will be found in the La Tour articles in the Dictionary. For Charles we have to content ourselves with the copies in other media, of which perhaps the most reliable is the slavish engraving by Michel Aubert.  Since Aubert died a few years later and the print created while artist and sitter were still alive, its documentary value is indisputable, and I think this is enhanced rather than diminished by the fact that he didn’t reverse the sash of the Garter: my guess is that he thought it was the Saint-Esprit as worn by the Dauphin, which he also engraved after La Tour in 1747.

Since Aubert died a few years later and the print created while artist and sitter were still alive, its documentary value is indisputable, and I think this is enhanced rather than diminished by the fact that he didn’t reverse the sash of the Garter: my guess is that he thought it was the Saint-Esprit as worn by the Dauphin, which he also engraved after La Tour in 1747.

One puzzle raised by Corp is easily disposed of: the green ribbon of the Order of the Thistle in the Edinburgh pastel has faded to blue simply because that was what happened to mid-eighteenth century green pastel. The colour was notorious (and the reputation of the famous Swiss pastel maker Bernard Stoupan rested on his ability to produce a stable green): it was usually made by mixing blue and yellow pigments, but while the former was stable, the latter was a vegetable extract from the buckthorn tree which was sensitive to light. My Twitter followers will remember some of the other examples, among them Liotard’s portrait of the maréchal de Saxe, whose green uniform now appears blue. And I shan’t begin to speculate as to the significance of the tide marks visible around Henry’s head, which possibly relate to alterations made by La Tour (don’t go there…).

But in the discussions of these Stuart portraits a vital role is played by the various copies that were made at the time. Jacobite portraiture, for obvious reasons, is both highly complicated and of greater interest to British scholars than to French specialists, and perhaps that is why several confusions have arisen which should be addressed (even if the outcome is to restore rather than to remove question marks). Indeed not all these copies have survived, and the hazard of discussing ill-documented lost copies of lost works (which may indeed be after quite different portraits) is obvious. But I would direct readers in particular to Corp’s entirely justified health warning about the reliance placed on the typescript notes assembled by Clare Stuart Wortley in the 1940s, a document which she was unable to complete before her death and which includes several tantalising references to correspondence which cannot be verified. Perhaps like Fermat she was right; but let us hope the letters are found with less effort than a proof of his theorem.

One of the difficulties is where a copyist is named in the source, but a later commentator supplies a forename, often from the nearest reference book. Thus (I suspect) when we are told that in September 1747, Prince Charles sat for a miniature portrait by Georges Marolles, can we rely on the “Georges”? I am not aware of any miniaturist of this name, and I suspect the reference should be to Antoine-Alexandre de Marolles, a well-known miniaturist who worked for the French royal family and is represented in Chantilly (see Lemoine-Bouchard 2008 for more).

One of the engravings derived from the La Tour portrait of Charles is by Petit fils (not Gilles-Edme, but Gilles-Jacques Petit) after Mercier (1753). Corp 1997, who reproduces it (fig. 36), judiciously puts a ? before the predictable identification of “Philip Mercier” which now appears without qualification in most sources (the same picture is evidently the source of the Ab Obici Major mezzotint). But it is biographically and stylistically improbable that the English Huguenot painter (born in Berlin) would have made a copy after La Tour for the Irish Jacobite Colonel O’Sullivan to be engraved in Paris by Gilles-Jacques Petit. It seems to me far more probable that the artist concerned was Claude Mercier, the pastellist who might well have spent some time in La Tour’s studio. His work, which is entirely French, is usually signed “C. Mercier” and inevitably given to Charlotte Mercier, Philip’s daughter, despite the absurdity discussed in my article on him. It is not improbable that the unknown man now in Mapledurham was another Jacobite. As for Mercier’s copy of the La Tour, that (like so many of these works) is lost: O’Sullivan later fell out with Charles, not over the colonel’s incompetence on which many blame the disaster of Culloden, but over a mistress.

Corp 1997, who reproduces it (fig. 36), judiciously puts a ? before the predictable identification of “Philip Mercier” which now appears without qualification in most sources (the same picture is evidently the source of the Ab Obici Major mezzotint). But it is biographically and stylistically improbable that the English Huguenot painter (born in Berlin) would have made a copy after La Tour for the Irish Jacobite Colonel O’Sullivan to be engraved in Paris by Gilles-Jacques Petit. It seems to me far more probable that the artist concerned was Claude Mercier, the pastellist who might well have spent some time in La Tour’s studio. His work, which is entirely French, is usually signed “C. Mercier” and inevitably given to Charlotte Mercier, Philip’s daughter, despite the absurdity discussed in my article on him. It is not improbable that the unknown man now in Mapledurham was another Jacobite. As for Mercier’s copy of the La Tour, that (like so many of these works) is lost: O’Sullivan later fell out with Charles, not over the colonel’s incompetence on which many blame the disaster of Culloden, but over a mistress.

But a particularly important piece in the jigsaw is a miniature (with various repetitions) which has caused great confusion. One of these (whether it is the “primary” version can be debated) is apparently signed “J. Kamm 1750” on the reverse. It belonged to Donald Nicholas who reproduced it in his 1973 iconography on the prince. It, and all the related miniatures (which although unsigned appear to be by the same hand), now appear as by “John Daniel Kamm” (sometimes as Jean-Daniel Kamm, and with various dates for his birth and death almost always wrong), and immediately provoked my suspicion as to whether this is the right Kamm, or simply the one found in the first reference book that came to hand.

It belonged to Donald Nicholas who reproduced it in his 1973 iconography on the prince. It, and all the related miniatures (which although unsigned appear to be by the same hand), now appear as by “John Daniel Kamm” (sometimes as Jean-Daniel Kamm, and with various dates for his birth and death almost always wrong), and immediately provoked my suspicion as to whether this is the right Kamm, or simply the one found in the first reference book that came to hand.

Here is what we know about Johann Daniel Kamm. Like his father, Johann Peter Kamm, he was a potier d’étain (a somewhat grander profession than it sounds following Louis XIV’s decree that solid silverware be surrendered t o the treasury, but not an orfèvre). Johann Peter’s wares included highly decorated objects of museum quality (e.g. Kunstgewerbemuseum, Dresden). Johann Daniel specialised in commemorative medals, of which one of the best known (signed I D KAMM) marked the exhibition of Clara, the Dutch rhinoceros, in Strasbourg in 1748 (you may know her from Oudry’s painting, the centrepiece of a Getty exhibition in 2007). Far later (1779) he issued a medal to mark the inauguration of the mausoleum to Maurice de

o the treasury, but not an orfèvre). Johann Peter’s wares included highly decorated objects of museum quality (e.g. Kunstgewerbemuseum, Dresden). Johann Daniel specialised in commemorative medals, of which one of the best known (signed I D KAMM) marked the exhibition of Clara, the Dutch rhinoceros, in Strasbourg in 1748 (you may know her from Oudry’s painting, the centrepiece of a Getty exhibition in 2007). Far later (1779) he issued a medal to mark the inauguration of the mausoleum to Maurice de  Saxe (signed D KAM: note the D again). His last known work was dated 1790. He died in Strasbourg in 1793, having married there in 1758, and his career seems to have been conducted in that city.

Saxe (signed D KAM: note the D again). His last known work was dated 1790. He died in Strasbourg in 1793, having married there in 1758, and his career seems to have been conducted in that city.

There is however some evidence that he visited Paris, most readily found in Johann Georg Wille’s journal. This is particularly relevant since the other important portrait of Charles at the time of the La Tour was by Tocqué (given it is said to his mistress the princesse de Rohan, née Marie-Louise-Henriette-Jeanne de La Tour d’Auvergne (1725–1781)), and it was engraved by Wille at around the same time as the miniatures were produced; further there is a signed miniature by Kamm after the Tocqué (reproduced in Piniński’s recent biography, fig. 3, detail on the cover shown here).  Wille’s journal refers to visits of his friend Kamm to Paris in the 1770s. Although it is the editors who supply Kamm’s forenames, Wille refers to exchanging medals etc. (supporting the identification as Johann Daniel), and evidences Kamm’s links with Silbermann the organ builder. The Silbermann-Archiv has numerous references to this Kamm: he was in Paris in the 1750s and made a sketch of the organ at Notre-Dame for Silbermann.

Wille’s journal refers to visits of his friend Kamm to Paris in the 1770s. Although it is the editors who supply Kamm’s forenames, Wille refers to exchanging medals etc. (supporting the identification as Johann Daniel), and evidences Kamm’s links with Silbermann the organ builder. The Silbermann-Archiv has numerous references to this Kamm: he was in Paris in the 1750s and made a sketch of the organ at Notre-Dame for Silbermann.

But despite this I can find no evidence that Johann Daniel Kamm was a miniaturist or even a portraitist (although the engraved portraits on medals requires some drawing skills). Wille doesn’t refer to him as an apprentice or as an engraver.

I confronted essentially the same problem when cataloguing Perronneau’s work. In the Salon de 1750, he exhibited a lost pastel described simply as:

![]()

I decided in 2006 that this was more likely to be the portraitist and miniaturist Jean-Frédéric Kamm, who was reçu at the Académie de Saint-Luc in 1759 (when he lived in Paris, rue du Colombier). When Dominique d’Arnoult published her catalogue raisonné on Perronneau recently, she followed this identification, and unearthed entries in the Chantilly accounts for Kamm’s work for the maison de Rohan-Soubise, at the same time that Perronneau worked for them:

Peintres en portraits: Kamme – De celle de onze cent quatre livres payee au Sr Kamme peintre du Roy de Pologne sur les ordres par Ecrit de S.A. pour des portraits par lui faits Sçavoir : 3 mars 1752 600 l.t. ; 28 juin – 504 ; 1104 l.t.

It may not be coincidence that Prince Charles had close connections with the Rohan family, and his mistress in 1748 was of course the princesse de Rohan: but even more suggestive is the reference to J. F. Kamm in 1752 as “peintre du roi de Pologne”, i.e. Stanisław Leszczyński. This is because, soon after the liaison with the princesse de Rohan, Charles Edward turned his attentions to the princesse de Talmont – who had previously been Stanisław’s mistress (and was closely related to both her lovers). And it was she who badgered George Waters, Charles’s banker, to borrow the La Tour pastel so that it could be copied. Only three days would be required, she pleaded, for a copy to be made by M. Le Brun (not identified in the Jacobite sources, but surely Michel Le Brun, brother-in-law of Jean-Baptiste Van Loo). In fact she had the portrait for far longer. The Le Brun copies are not known, if they ever existed; and there is every reason to suspect that she might have engaged the services of the peintre du roi de Pologne.

But how, you may ask, do I explain how Johann Friedrich Kamm copied Tocqué’s portrait when it was Johann Daniel who was so close to Wille? The copy of course was probably made from the painting, not the print; but probably while it was in Wille’s studio. But in fact we can demonstrate that Wille knew and supported Johann Friedrich as well as Johann Daniel Kamm. This comes from an announcement in the German journal Wochenstück, 24. Mai 1756, S. 161 :

This reports J. F. Kamm’s appointment as an honorary member of the Kaiserlich Franciscianischen Academie freier Künsten und Wissenschaften in Augsburg. Just a month before (29 April 1756), it was Wille himself who was appointed “als ein Ehren-Glied, und Consiliarius Academicus” – and impossible to imagine that his academic advice had not extended to recommending his protégé.

So, in contrast to Johann Daniel, there is clear evidence that Johann Friedrich Kamm was a talented miniaturist who worked for royal houses and was in Paris at the right time. One would have thought that he was obviously the “J. Kamm” who signed both miniatures. But it isn’t quite that simple.

Several sources cite, with not a little confusion, a letter from Waters to the prince, written we are told in 1749, referring to miniatures by one Kamm. Most recently Corp 2009 notes that the letter is not to be found where it is supposed to be in the Stuart papers, and cannot be located. This is particularly frustrating since the description of it given by Clare Stuart Wortley is as follows:

In the year 1749, George Waters writes to Charles about copies of his portraits being made by Jean Daniel Kemm. Copies presumably from the La Tour portrait.

If “Daniel” appears in the Waters letter, then evidently I am wrong – but not if it is Stuart Wortley’s gloss. The misspelling of Kamm looks as though she is quoting directly (unlike Nicholas, who refers to John Daniel Kamm). But until the letter is located the issue cannot be resolved.

There is one further question to be asked. How were these Kamms related? It’s not as simple as you might think. The matter is complicated by the existence of a third artistic Kamm: Jean (tout simple) Kamm, who is recorded as a pupil of Doyen enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris from June 1767 (aged 19 years 9 months, so born in September 1747), “from Alsace” (which usually means born there). He was still on the books two years later, but is otherwise completely unknown. However two further details are recorded: in 1767 his address was “chez M. du Plessis médecin rue du Colombier vis à vis l’hôtel d’Holande”; while in 1769, it was “chez M. Cadet chirurgien rue du Maille. ”

The significance of the first address is not so much that “M. du Plessis” was a well-known freemason, Nicolas Huet-Duplessis, since at that time everyone was, and it doesn’t mean he was a Jacobite, but that the “rue du Colombier” is the same address as that recorded in the registers of the Académie de Saint-Luc when Johann Friedrich Kamm was reçu in 1757. Coincidence perhaps? But the second address is even more interesting: Aglaé Joly, the wife of Claude-Antoine Cadet, de l’Académie de chirurgerie, was a miniaturist and pastellist, while their daughter Henriette-Thérèse married the important enamellist and pastellist Jean-Baptiste Weyler (Strasbourg 1747 – Paris 1791), the son of another strasbourgeois butcher and his wife, née Maria-Salomé Kamm.

All of which suggests that Johann Friedrich and Jean were very closely related. And indeed the Nouveau dictionnaire de biographie alsacienne tells us that they, and Johann Daniel, were all brothers. But curiously they do not provide the dates for either Johann Friedrich or Jean, and having spent some hours among the parish records I fear that the statement may be overconfident.

Kamm may not be a common name outside Strasbourg, but the family of butchers who lived there at least from the seventeenth century were very numerous. Almost all the boys were given the first name Johann, followed most often by Daniel, Michael, Christoph etc.; all the girls were called Maria (don’t ask me what sect of Lutheranism this was), followed by Salome, Ursula or Catharina. So creating a reliable genealogy turns out to be far trickier than normal. (Here‘s where you start.) This compounded by the fact that there were rather a lot of different parishes in Strasbourg, and the fact that (for me at least) the German handwriting of the period is sometimes tricky. Here for example is Johann Daniel’s baptismal entry (which is much easier to read than most of the other entries):

Suffice it to say that (as far as I can see) none of the Johann Friedrichs share these parents, nor does Johann or Jean born in September 1747. And since Johann Daniel’s mother was born in 1690, it seems rather improbable that Jean can have been a full brother.

But then Jacobite enthusiasts always like a note of mystery. I note that the Royal Archives at Windsor are to close for several months for refurbishment. Is it too much to hope that some of Clare Stuart Wortley’s documents will resurface?

I read Lord King’s new book with curiosity and puzzlement. Since I’m not a professional economist (and it’s as much about economics as it is about banking – and it becomes clear just how different those disciplines are), I’m not going to “review” it, particularly since you have seen or will soon see plenty of column inches devoted to it. Most will take the usual tack of summarising it, which I shan’t. Because what’s most interesting is what’s not there.

I read Lord King’s new book with curiosity and puzzlement. Since I’m not a professional economist (and it’s as much about economics as it is about banking – and it becomes clear just how different those disciplines are), I’m not going to “review” it, particularly since you have seen or will soon see plenty of column inches devoted to it. Most will take the usual tack of summarising it, which I shan’t. Because what’s most interesting is what’s not there.

Before I go further let me state that I think the book is admirable in many ways. As a summary of the problems in banking, finance and economics, it is accurate, readable and informative. Unlike so many books about these subjects it doesn’t patronize, and although it avoids mathematics the ideas are explained with far more nuance and sophistication than in most popular accounts: so it can be read with profit (although in view of its message perhaps not with pleasure) by everyone. And there is added a wealth of cultured references which I certainly enjoyed – going beyond sport, the usual pool from which financial writers draw, to T S Eliot, Brecht, Swift and Hegel. An 1839 volume entitled The Political Pilgrim’s Progress proved particularly rich in parallels with the mess we are now in.

As I’ve said I’m not going to take you through the author’s argument. Alchemy is the transformation of maturities (where a bank lends long but borrows short) which he sees as the root of the instability that causes crashes of increasing frequency and amplitude. And he identifies the factors that exacerbate this, including “radical uncertainty” (which he refrains from calling unknown unknowns), and several other such concepts that will be familiar to anyone who follows this area: disequilibrium, the prisoners’ dilemma, and trust. He questions whether there is a fundamental weakness in economic thinking (and comes up with many), and whether we can preserve the benefits of capitalism but abolish alchemy.

It is what he says along the way that will be of most value to readers, offering intelligent and incisive discussions of many of today’s most important debates, such as what people mean by secular stagnation and whether lowering interest rates can create demand. He’s very good on the cognitive errors that persist around finance, and the deficiencies of economics as an intellectual discipline. But it is all the more surprising that when he comes up with suggestions they seem almost naïve.

Thus his prescription for ending alchemy consists in replacing the central bank’s role as lender of last resort (for which he introduces the acronym LOLR, making me wonder if my social media skills are current) with that of “pawnbroker for all seasons”. The key feature of PFAS is essentially that each bank pre-agrees its assets with the central bank, as well as the level of “haircut” to be applied to each class of asset, so that there is a committed but normally undrawn facility from the central bank which is able to cover liabilities maturing within the next 12 months. He sees this as the panacea (rather than additional equity, which is merely desirable). But there is no discussion of whether in practice the central bank would be able to deal with a market panic where all commercial banks needed to draw these lines at the same time; nor what happens at the end of 12 months (an odd omission given that the last crash took far longer than that to unwind); nor what happens to the astronomical derivatives positions that are not reflected on the balance sheet; nor whether the collateral would actually be delivered (he does not discuss the widespread concern about the bankruptcy analysis of rehypothecation as it is increasingly practised in the City).

And the concept seems to remain focused within the central bank’s perspective: a mere tweak of the Bagehotian formula of lending on collateral. Even though King is sound on the arithmetic of collateralised lending (in the one example in the book that comes close to numbers), he fails to draw the obvious inference that any secured borrowing destabilises a bank’s position by making it impossible to borrow unsecured except from stupid or uninformed depositors.

King also fails to grasp the nettle of uninsured depositors and the rate of interest they should require: while seemingly acknowledging politically that such depositors would have to be bailed out, not in, next time, and while being fully conscious of the moral hazard and other implications of saying so, he does not seem to feel strongly (or at least not explicitly) that the current ambiguity is outrageous.

That in essence is my puzzle with this book. It is too civilised; too well written; too elegant. He describes a mess far deeper than most commentators or politicians have acknowledged, and is realistic about the chances of rectifying the situation before the next crash, but where is the anger?

Perhaps the answer is at the back of the book. Lord King is now a knight of the Garter, whose motto, you will recall, is Honi soit qui mal y pense. He has lifted up the skirts and found the indescribable. The true alchemy here is the distillation of the sæva indignatio into a courtier’s polish. One which will allow politicians to do with this book what they would anyway – ignore it.

“The first duty of a critic is to lavish unalloyed praise”, Lawrence Gowing is said to have told the young Brian Sewell (according to an article Sewell wrote for the December 1990 edition of The Art Newspaper: it was entitled “This ‘profession’ has much in common with prostitution”, and it won’t surprise you that he did not share Gowing’s view). The words came to mind some six months ago, after I had visited the first leg of the Liotard exhibition in Edinburgh and was keen to compare my views with others’. I penned a first draft of this post, but shelved it in order to wait for a more complete picture of the state of British journalism.

What do you want from art criticism, at least in the form in which it appears in the newspapers? Perhaps you are content to be told whether or not to go to an exhibition: for that a simple star rating should suffice. Maybe you want a little hint at what you will see, in case the title doesn’t give enough away. Maybe you need to be enthused: this artist is important; you will never get another opportunity to see this again; and so on. Or maybe you expect something more: analysis of the exhibition, new angles and insights that enhance your enjoyment and deepen your experience of the works to be seen. And perhaps a critical assessment of how well it has been put together: did the organisers choose the best examples, arrange them with intelligence, light them with skill and design the displays with taste? (Ideally of course, did they find new, convincing additions to the oeuvre?) Was the artist “contextualised”, in the jargon – that is, compared with his contemporaries and placed in the cultural environment? Was the catalogue well written, informative and accurate? Were the attributions correct?

Perhaps you want to leave the last of these questions to specialist journals: the Burlington Magazine, for example, has frequent displays of scholarship (Pierre Rosenberg’s review of the Poussin exhibition a few months ago is exemplary), often in the small print notes at the end of many of its reviews, which you wouldn’t expect to find in the Guardian (although let us remember that Brian Sewell never dumbed down his contributions to the Evening Standard). But I think you will probably expect more that a rewritten press release.

In the immediate aftermath of my visit to Edinburgh (July–August 2015), I saw four reviews: in the Sunday Times, the Financial Times, the Observer and the Spectator. All were unanimously enthusiastic, and perhaps one should ask for no more. Although none stooped to awarding stars, it is clear that a full, or nearly full, complement would have been earned, and the target of attracting visitors no doubt achieved. But in reviews of up to 1200 words each, one craves more.

Here is just what we want, from the Financial Times:

Liotard, Nelthorpe (Bath, Holburne Museum)

In Edinburgh, a bust-length 1738 portrait of James Nelthorpe shows the young man in an extravagant white-and-scarlet turban and robe lavishly trimmed with black fur. Rippling through furrows of darkness and ridges of shimmering colour, this tour de force of stroke-making testifies to how effortlessly pastel can lend itself to opulent surfaces.

This is impassioned writing, informing us of the author’s aesthetic response to a picture, making us want to go and see it for ourselves and see whether we experience it in the same way. There’s only one problem (and perhaps a second – see below): the picture of Nelthorpe wasn’t shown in Edinburgh (it only joined the exhibition in London in October: we don’t know how the journalist reacted when, as I hope, she eventually saw the picture in London). Nor was this reviewer the only culprit: the Observer too mentioned the pastels of the Thellusson couple, who were also not to be seen in Edinburgh.

The critic in the Sunday Times didn’t make this mistake. Instead he devoted much of his space to a rather silly play on the names of Liotard and Lyotard, the literary theorist who invented the concept of “metanarrative” into which the writer promptly attempts to slot the pastellist. In a tweet promoting his piece, he claimed to be the first to put together Liotard and Lyotard: sadly this is untrue, as a rather clever footnote in a 1998 colloquium of Michel Butor notes “Comme le a de différance, la différence entre Lyotard et Liotard (qui va revenir) est, dans la communication performée, muette.” But this wordplay didn’t really tell us much about Liotard, not least because most Sunday Times readers probably won’t know much about Lyotard (or Butor or Derrida, or indeed différance), if I’m allowed to patronise in turn.

All these reviewers seem to have accepted without challenge the claims in the organisers’ publicity that Liotard is the greatest artist of the 18th century whom nobody knows. One critic, better known for his interest in contemporary art, told us in a national newspaper that his “expectations were low [as he had] never heard of the subject of the show.” Another tells us that “no country has taken it upon itself to celebrate [Liotard] as a national treasure” (ever been to Geneva?); a third that “for anyone not schooled at the Courtauld, Liotard is likely to be as obscure as Bailey [the photographer, on show at the same time] is recognisable”; a fourth that Liotard is lost in between Watteau, Boucher and Mme de Pompadour: but this is the metanarrative of the Wallace Collection. (In fact the Courtauld isn’t too enthusiastic about pastellists either.) So effective has the RA publicity been that I even had a number of strangers come up to me in the exhibition to tell me they had never heard of Liotard. Does this happen at say the Francis Towne exhibition? Normally we are embarrassed by ignorance, not prompted to convert it into a boast that combines John Bullism with the real secret of this exhibition – that Liotard is the pastellist liked by those who don’t like pastel.

The trouble with all this is that it ignores the fact that Liotard is actually extremely well known to anyone genuinely interested in eighteenth century art, and not just to Marcel Roethlisberger and Renée Loche who have devoted lifetimes of research culminating in a brilliant catalogue raisonné. Curiously the FT critic noted that Liotard had been the subject of exhibitions in Zurich (1978), Paris (1985), Geneva (2002) and New York (2006) (to which one might add Utrecht and Amsterdam) – but didn’t seem to draw the obvious conclusion. And while the Sunday Times critic may go on and on about Ramsay and Raeburn, but never hears about Liotard, that isn’t reflected in the literature: Liotard has more entries in the International Bibliography of Art than Ramsay and Raeburn together. And, although it is a relatively recent phenomenon (dating to the purchase in 1986 by the Houston Museum of Fine Art for a spectacular sum), Liotard is also the darling of the salerooms.

What I look for from art criticism is a broader wisdom. Not an acceptance of the press releases, but a challenge to the assumptions brought either by the organisers or by the public. I want to be given an international perspective and to be told that in Geneva and in Amsterdam there is a profound respect for this artist, and brilliant examples that cannot travel. I want to have the contentions in the catalogue challenged by people who bring a deeper knowledge of the subject, not those to whom the subject is a surprise – let alone a complete mystery. I want to be provoked into scholarly debate, perhaps pointing to new facts and discoveries. And I want to know whether the exhibition works: is it just as a group of pictures put in a room, or does a coherent message emerge that amounts to more than the sum of the parts?

That is as far as I got six months ago. In fairness we did get in Apollo in October an informed, accurate and balanced account of the Edinburgh show (from Stephen Lloyd, a specialist: it shows, notably in understanding the different media included), albeit severely limited by the space allotted, but with an acknowledgement of the difficulty of borrowing pastels (so that the finest collections, in Amsterdam, Geneva and Dresden could not be included) rather than an acceptance that the problems of transport had been solved. I’ve written about that in a different post.

When the exhibition switched to London, I hoped we would see more of what I was looking for. Instead we got a flood of reviews (the RA press machine is certainly not to be faulted in its efficiency), but almost all covering exactly the same things (and with exactly the same deficiencies) as the initial flurry. We had it is true contributions from a wider range of backgrounds. One critic, who is a practising painter with an artist’s visual sense, announced the resounding “blare of intense copper-carbonate blue”, which immediately makes us pay attention to such wisdom. But numerous pigments, many copper based (not necessarily copper carbonate) can give rise to these blues, and the paper conservators who specialise in Liotard pigments are unable to make this determination without spectroscopy. Another artist–reviewer devoted just over 100 words to the exhibition catalogue, which it suggested “surveys the artist’s pastels” and provided “succinct but thorough information about each of the 82 exhibited items”, without any indication that fewer than half were pastels.

A different approach was taken by the writer Julian Barnes, who in fairness wasn’t reviewing this exhibition at all. His piece was about the exhibition on prostitution at the musée d’Orsay, which interested him (and about which he wrote with fierce intelligence), and about the Vigée Le Brun at the Grand Palais, which did not (and that comes across in his singling out for praise the worst, and least typical, painting in the show). But as a put-down, he included this comment:

Compared to, say, Liotard she [Vigée Le Brun] seems hidebound. The Swiss painter had a similarly peripatetic life and well-born clients. But set Alexandrine-Emilie Brongniart beside Liotard’s Princess Louisa Anne of 1754: Le Brun shows us what we might prefer to imagine childhood to be like; Liotard gives us the existential lostness of a little girl in a dress too big for her and a lace cap that looks silly not stylish.

I should have liked more of this sort of analysis. It makes one think, and makes one want to go back and look differently. And that’s certainly a valid contribution. But I’m not sure that it constitutes art historical scholarship.

For that we have had to wait, sadly until after the show is about to close, as it would have been useful to have the challenges set out while there was still time to march round the exhibition with the review in hand. (I’m not referring to my own blog post: a list of errata is not a review, whether you dismiss it as the rantings of a Beckmesser or agree with the cumulative weight of those observations.) But at the same time, one recognises the advantage of waiting for a good exhibition to mature; one goes back again and again (more than a dozen times in my case), and one sees things one hadn’t observed at first: so a reviewer’s first thoughts are rarely the last word.

The piece I allude to is indeed in the Burlington Magazine (February edition), and it is written by Alastair Laing: uniquely placed to do so, by virtue of his profound knowledge of both British and continental art of the eighteenth century, of his acute eye and of his track record of challenging accepted assumptions. His review of the 1992 exhibition of Liotard drawings was a major contribution to correcting the errors in that show. I haven’t yet received my copy of the magazine, but I glanced at it very hurriedly this afternoon in a bookshop, and I can alert you to the fact that it raises questions of attribution of several pictures, among them the Nelthorpe discussed above and David Garrick. I’m posting this article now so that as many of you can see it, and get back to the exhibition before Sunday, to look at the items in question.

I’ll leave my considered views on these specific points for a later post. But it is this kind of debate that has been so conspicuously lacking to date.

Postscript – 1 February 2016

Alastair Laing observes that the catalogue has not attempted to go into detail about the exhibited works in view of the recent appearance of Roethlisberger & Loche (for my review of which the Burlington curiously fails to follow its normal convention of footnoting), but he nevertheless suggests that the curators should have “devoted greater consideration to the individual exhibits” – while falling short of outright rejection for Nelthorpe and Garrick. (He does however reject the Duncannon oils, as I discussed in my errata post.) Garrick merits a fuller discussion, but doubts about Nelthorpe are I think misplaced.

Visually of course this is far less accomplished than the great Liotard pastels we normally expect to see. But it is far earlier than most of his work, was probably made in Constantinople where he didn’t have the materials he would later use (so that the colour range is restricted – a little less so had we been allowed a glimpse of the blue cummerbund concealed by the later gilt slip); the pastel is on paper, and is in poor condition (the work was transferred onto board some years ago, with losses and restorations whose extent is a matter of guesswork).

Who else would have done it? Knapton, perhaps, might be suggested, particularly because, among the few things we know about Nelthorpe was that he was a member of the Society of Dilettanti. But he joined after that club had introduced a rule saying that the portraits members had to offer were to be in oil. So presumably the narrative becomes: Nelthorpe commissioned Knapton to do his portrait for the Society, but the pastel was rejected. If so you would expect the pastel to have remained in Nelthorpe’s collection: but not only did it not figure in his posthumous sale, nothing like it did either (Nelthorpe had a vast collection of engravings, but doesn’t seem to have commissioned original portraits). It is I think more probable that this is the “Mr Nelthorpe in Turkish costume by Liotard” recorded in Sir Everard Fawkener’s collection. And it is not so very different in quality from the equally flat, but signed, comte de Bonneval, which has never been questioned.

There are two specific, but telling, weaknesses in the Nelthorpe pastel. The first is the rather poor treatment of the fur, with a central section of completely flat lighter hue. At first sight this looks like the efforts of an inept restorer. But as you went round the Liotard exhibition, you found exactly the same effect in several other works – e.g. William Constable and Lady Guilford. A busy restorer – or a particular incompetence of this artist?

The second passage is the intersection of the nose with the more remote eye. It is certainly an extreme example, but there is repeated evidence throughout Liotard’s career of his difficulty in this passage: this may perhaps explain his predilection for the lost look, where the problem is avoided. But in other cases (perhaps the most obvious cases in the exhibition were Lady Anne Conolly and Isaac-Louis de Thellusson), Liotard has a tendency to divide faces vertically, with the two halves occupying different planes. The effect is Picasso-like, but gives his sitters a distinctive, geometric feel. I think the Nelthorpe error is an early manifestation of this. For all these reasons, I have retained the attribution.

PPS – 4 February

I’ve only just seen this review in a Swiss online journal. I think it provides an interesting international dimension to the British commentaries. Etienne Dumont, an art critic from Geneva, is troubled by the inevitable gaps in the coverage, notes that the English public liked the show, but concludes that “Du peintre, ils ont un aperçu. Un aperçu seulement.”

Mlle Thomasset after Liotard, self-portrait, needlework (Vevey, musée Jenisch)

The Thomassets were my entry point for a previous post about Liotard in London (but the surrounding material merited longer treatment), and in particular an erroneous statement in a recent publication that Liotard stayed with them on his first London trip. (He was then located in Golden Square, as that post explained.) They were his neighbours during his second London trip.

All the more confusing because the Thomasset house, 18 Great Marlborough Street (later the premises of Erard, the piano makers), on the north side, is indeed opposite the other “Blenheim Street” (i.e. the alley leading down to Carnaby Street). It lies about 50 metres west of Liotard’s house, on the opposite side.

Mrs Thomasset was a Swiss widow of 62 years of age who had moved to London in 1749 with five of her daughters (aged between 21 and 41), and established a school for young ladies. One of the daughters took up “needlepainting”, or the copying of paintings in embroidery, made popular in London by Mary Linwood (the dates make it hard to determine who influenced whom, particularly since Mary’s mother Hannah Linwood also exhibited needlework, but it seems difficult to believe they both developed this mode independently). Mlle Thomasset made copies of about 20 English and old master pictures, including the Liotard self-portrait exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1773 and acquired by Bessborough (now in Geneva, R&L 447, reproduced in the previous post; her copy is above). They are now in the musée Jenisch in Vevey.

“Mlle Thomasset” (variously identified as Hélène, Julie or Octavie) has been known in Liotard studies for ever: she appears in Humbert, Revilliod & Tilanus’s 1897 monograph as the brodeuse responsible for embroidered copies of pictures, Liotard’s self-portrait among them (the authors however had not seen them); the family’s emigration to London is mentioned very briefly, as is the fact that the pictures had now found their way into the museum in Vaud. Fosca got carried away and declared all the works to be by Liotard, while R&L gave a correct if incomplete account, identifying the artists of some of the other works – among them portraits of Garrick by Gainsborough etc. The discussion is at R&L p. 590 and I won’t repeat all of it: but the family’s London stay is sketchy to say the least.

Here anyway (and with all necessary caveats) is Fosca’s description:

Ils comprennent d’abord ce que l’on appelait autrefois des « têtes d’expression » – un vieillard, une Sibylle, etc. – puis des paysages dans le goût hollandais, assez conventionnels, et ne rappelant en rien son admirable Vue des glacieres de Savoie du Musée d’Amsterdam. En revanche, d’autres sont bien plus intéressants, et nous offrent une traduction très fidèle de portraits que Liotard avait exécutés vers cette époque-là. Ainsi, l’un est une copie en broderie du portrait de l’artiste âgé et sans barbe, le menton dans la main, qui est au musée de Genève et que Liotard exposa en 1773 à la Royal academy. Deux autres montrent un jeune Chinois coiffé d’un chapeau conique, et un domestique en livrée; ils durent être executes d’après des tableaux que Liotard peignit pendant son séjour en Angeleterre. Un portrait de Garrick, qui n’est pas le même que celui de Chatsworth, représente le fameux acteur émergeant d’un œil-de-bœuf, le bras tendu et tenant à la main un livre ouvert. Un autre broderie montre Garrick dans le role du Roi Lear. Il est en pied, dans un paysage, et déclame en brandissant une épée.

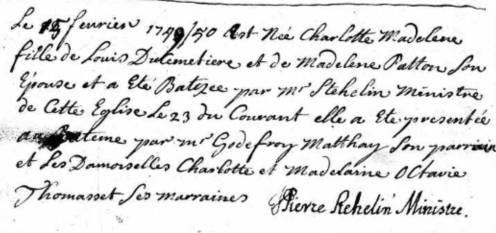

Sir Gavin Rylands de Beer, director of the British Museum and President of the Linnean Society, took up the hunt for the family in the context of Mlle Thomasset’s nephew, the eminent (if short-lived) botanist Edmund Davall (1763–1798). He published a series of short notes in the late 1940s (not cited in R&L) in which he made considerable progress with the genealogy, but still left a number of matters outstanding. Only one of the daughters seems to have married: Charlotte, who married a store-keeper of the Navy slop-office; they were the parents of the botanist. You can see why the name is misspelled so easily from the 1758 register entry:

Charlotte can be found earlier, in 1750, with her sister Madeleine-Octavie, as joint godmothers at the baptism in Leicester Fields Chapel (French Protestant) of another Huguenot (probably from the Genevan family to which the American pastellist Pierre-Eugène du Simitière belonged):

I won’t trouble you with a full rehearsal of the pedigree I have compiled as I was drafting this account: you can see it here. It explains the relationship with Lord Chesterfield’s private secretary (one of his granddaughters was apparently the prototype of the “inimitable Miss Larolles” in Fanny Burney’s novel Cecilia) and quite a number of other relatives with whom confusions have been made.

Among the very few accounts of the school we have Cornelia Knight’s autobiography: she was taken to the Mesdames Thompets [sic] in 1762, aged 5; she dreaded her time there “to a degree not to be described”. (In contrast she greatly enjoyed her drawing lessons from Sir Joshua Reynolds’s sister Frances.) She noted that “the too famous Marat was a Swiss physician and used to visit us at the school.” Dancing was taught by Noverre, brother of the celebrated subject portrayed by Perronneau.

But which of the ten Thomasset sisters was responsible for the embroideries? Davall’s correspondence notes that his remaining living aunts devoted themselves to playing quadrille, from which de Beer inferred that the brodeuse was the sister who died in 1789. But elsewhere she was identified as Hélène. The thirteen siblings were born between 1708 and 1728. There are several Swiss guidebooks which mention (R&L don’t cite them) Mlle Thomasset: Louis Reynier, Guide ds voyageurs en Suisse (Paris, 1791, but written in 1788) writes–

If the 60 age is accurate, this would place her birth at close to 1710 (within a couple of years), assuming she made the Liotard contemporaneously. (R&L do cite Sophie von La Roche, 1792, who says the artist started aged 50 rather than 60.) In any case she was certainly dead before 1795 (R&L give Nagler’s date of 1796), because François-Jacques Durand’s Statistique élémentaire (Lausanne,1795, ii, p. 388) refers to “Feu Mademoiselle Thomasset.”

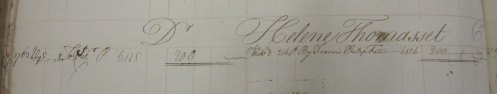

An examination of the girls confirms that the name of Hélène, which R&L put forward with a question mark but is the name favoured in the various sources, perfectly fits the information we have, and supports Reynier’s version. Two further pieces of information confirm this. One is Hélène’s will:

Je donne a mon neveu Edemon Davall aprai la mor de toutes mes soeurs mes tablaus en ca qui setablice den ce paï autremen mes soeurs en disposerons a leur gré…

One hopes that she was not responsible for teaching grammar or spelling at the school. But she has also signed one of the needlepaintings, on the letter held by the footman “A Mademoiselle/Helene Thomasset/Chez Elle”:

Mlle Thomasset, A footman with a letter, needlework (Vevey, musée Jenisch)

If this is Fosca’s “domestique en livrée”, I doubt whether it was done in London in view of the language of the address; but the liveried black servant may remind us of Baron Nagell’s, in the Ozias Humphry pastel now in the Tate. Perhaps someone can identify the livery (hint: a footman’s livery is supposed to reflect the colours of his master’s arms, so they should be azure, charged with or).

Hélène-Louise Thomasset (Agiez 11 February 1710 – Orbe 11 March 1782) has left little further trace of her existence beyond the pictures. I can however add some information about the sisters’ finances, culled from the archives of the Bank of England. Starting in 1760 Hélène bought £200 of the Bank of England’s 4% Annuity 1760 (one of the bank’s perpetual stocks later known as Consols):

Courtesy of the Bank of England Archive

Her sister Octavie did the same the following year; she was then living in Soho Square. By 1766 the holdings had been transferred into a joint account in the names of Hélène-Louise and their eldest sister Anne-Jeanne-Louise “Nanette” (1708–1792), who was living with Hélène in Great Marlborough Street throughout. By 1773 their holdings amounted to the sum of £3600, and were growing at the rate of about £500 a year. (Some care is needed with these sums, as the Bank of England ledgers record only nominal amounts rather than market prices, but yields remained fairly constant between 1762 and 1773 at around 3½%. The sisters may also have had holdings in other stocks.)

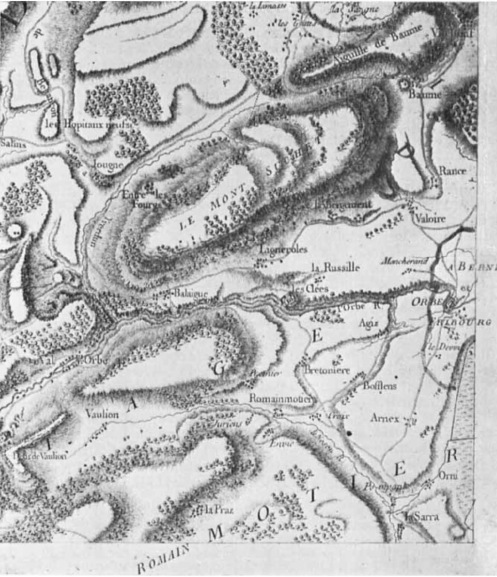

By 1777 the sisters (Mrs Thomasset had already died, at an unknown date) decided to return to Switzerland. On 26 March 1777, through their cousin, they purchased (while still in London)

une maison avec une terrasse devant, une grange, une écurie, une cour avec un bûcher deux jardins en deux terrasses, le tout contigus et battis à neuf et tel qu’il est situé dans la ville d’Orbe à la rue dite la Boucherie et encore une vigne derrière la maison d’environ quatre ouvriers.

Thus the Thomasset family, who were reported as leaving Switzerland because they were poor, went back comparatively rich, as is confirmed in a letter from an Irish traveller to Switzerland, Blayney Townley Balfour (several Jacobite pastels by La Tour and Hamilton were at Towneley Hall), who wrote home to his mother in 1788–

I have been but once out of this House at any Parties. It was at a Madam Thomasy’s who once kept a very famous Boarding School in London & is with a couple of her sisters retired to spend the Remainder of her Days in Swiss opulence upon £500 a yr. That is no inconsiderable Income here & they are one of the first Families here. There lives in the House with them a nephew of theirs, a Mr Daval, an Englishman…

Here, by way of contrast with London, is a map showing the house at Orbe where Hélène died (her sister Catherine died two days later), a mere 500 meters from Agiez (spelt Agiz in the map) where she was born:

Google Earth confirms that little has changed:

Some ten years after Hélène’s death, as we learn from Davall’s letters, Lady Spencer, the Duchess of Devonshire and Lady Duncannon visited Orbe during their stay in Switzerland in 1792. They all developed an interest in botany, but the Duchess preferred mineralogy. We are not told whether the ladies recognised Liotard from his portrait in needlework.

All this merely confirms what we knew already: that the Huguenot links between Switzerland and London provided a network in which Liotard and his clients moved comfortably.

One final aside, while we are on the subject of botany: another Liotard, Pierre (1729–1796), from near Grenoble, was for a long time rather more famous than the artist, and today is still known for his friendship with Rousseau (see this earlier post) – and for being killed by the fall of a stone sphere decorating the entrance to the Jardin des plantes in Grenoble of which he was in charge. Any relationship to the Genevan family would be distant.

Sources and notes

The best source on the family is Benjamin Baudraz, “Les Thomasset”, Bulletin généalogique vaudois, 2005, pp. 63–134, but as there are no copies in England I wrote most of this post before I was able to obtain it. The other sources are R&L; Survey of London; Fischer 2007, with Townley Balfour’s letter; Humbert, Revilliod & Tilanus 1897; Fosca; Gavin Rylands de Beer, “Edmund Davall, F.L.S., an unwritten English chapter in the history of Swiss botany”, Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London, CLIX, 1947, pp. 42–65; de Beer, “Thomasset”, Notes and queries, cxciv, pp. 445f; “The Thomassets’ school”, Notes and queries, cxcv, p. 54; Autobiography of Miss Cornelia Knight, lady companion to the Princess Charlotte of Wales, 1861; E. J. Burford & Joy Wotton, Private vices, public virtues, 1995, pp. 143ff (for Mrs Goadby). The pedigree is drawn from dozens of sources; for the sisters’ dates, the list on familysearch.org was unusually comprehensive and apparently reliable, unlike earlier sources. I am grateful to the Archives of the Bank of England for the unpublished entries in their ledgers. For Mary Linwood’s portrait of Napoleon, see here.

Liotard, Autoportrait, la main au menton, RA 1773 (Geneva, mAH)

A puzzle concerning “Mlle Thomasset”, which I shall discuss in a forthcoming post, has prompted me to look a bit more carefully into Liotard’s addresses during his two trips to London. There are no surviving leases, nor any entries with his name in the Westminster rate books, so the matter is not so simple as you might think.

On the second trip, Liotard arrived not in 1773, as appears in all published sources to date, but a few months earlier. This is evident from the minutes of the Society of Arts in November 1772 when he was approached to provide an opinion on Mr Pache’s crayons. You may have seen photocopies of the first few pages which were displayed in the Royal Academy exhibition (but found too late to appear in the catalogue; the subsequent pages are also worth reading as they contain interesting information about mildew and oxidation of Stoupan’s pastels: see treatises for the full text, currently at p. 31 of the pdf).

We also know – from the catalogue of his London exhibition in 1773, which is part of the standard corpus of Liotardiana – that he lived at Great Marlborough Street, facing Blenheim Street. But we haven’t until now known which house. There were two versions of the catalogue, one in French, in which the address was given as Great Marlborough-street, facing Blenheim-street; le nom de Liotard est sur la porte; in the English version, this is just as Great Marlborough Street, facing Blenheim Street, at Mr Liotard’s. The Royal Academy catalogue adds nothing, repeating the same formula. But from the advertisement in the St James’s Chronicle for 6–9 February 1773 (which I published in 2013), we get Mr Liotard, at Mr Henry’s, in Great Marlborough Street, facing Blenheim Street:

6 February 1773 being a Saturday, the exhibition opened 1 February 1773. The advertisement (identically worded) was repeated in the Public Advertiser between 25 and 27 March, and again on Tuesday 30 March; the exact date of closure is unknown, but presumably very soon after.

Some care is required in reading this. Londoners will be surprised at the mention of Blenheim Street at all, since that is not proximate to Great Marlborough Street today: but in 1773 the street now known as Ramillies Street was so called (of course none of these names would have been comfortable for French visitors). But so too was the short alley at the south west corner of Great Marlborough Street, leading down to Carnaby Market. Here is J. G. Bonnisselle’s map showing the streets as at 1772 for you to situate the geography:

So how do we know even if he lived on the north or south side? This is where Mr Henry comes in. By a careful examination of the Westminster rate books (noting the complexities of the hierarchies of tenure etc.) we find him between two properties owned by Walter Farquhar – later to become physician to the Prince of Wales and a baronet – and also between properties taken on by the pastellist-turned-property developer calling himself Calze (Edward Francis Cunningham), unsuccessfully trying to evade his creditors. Mr Henry’s property, on the south side of the street, must have been at no. 50, directly opposite Ramillies Street. Subsequently the street numbers were changed, the buildings demolished, a church erected and it too demolished to make this properly confusing (I’m not sure if I can persuade English Heritage to erect a blue plaque, as one of the conditions is that “the building must survive in a form that the commemorated person would have recognised”: that knocks out Perronneau as well). Little is known about John Henry, but he evidently kept lodgers (another put a notice in the Daily Advertiser in 1772 using his address).

Great Marlborough Street, as described by John Macky in his Journey thro’ England of 1722, “though not a Square, surpasses any thing that is called a street in the Magnificence of its Buildings and Gardens, and inhabited all by prime Quality.” No contemporary image is available, but it had obviously gone off a bit by Liotard’s day (it had further to fall before Dickens described it as “one of the squares that have been”). There were noble lords Onslow and Byron (William, the wicked 5th Baron notorious for murdering a neighbour), as well as Lord Charles Cavendish, uncle of the Countess of Bessborough. But neighbours also included Mrs Jane Godby, better known as Mrs Goadby, the brothel keeper whose most famous alumna was Mrs Armistead (aged 22 when Liotard arrived, she had already been painted by Reynolds). Among the Swiss community were Anthony Girardot, a relative of Mme de Vermenoux. And the Thomasset family – to whom I shall return in that separate post. Shortly.

The English Liotards

Something about both Liotard’s London visits has always struck me as odd. He seems to have had no contact with his two nephews (see the Liotard pedigree for the connection) who had settled there and become merchants. Both John and Mark Liotard were naturalized by Act of Parliament – the former, who was born in 1713, by 24 Geo. II, no. 7 [1751], the latter, born 1717, by 20 Geo. II, no. 83 [1747]. Both were mentioned in the 1750 will of the legendary Anglo-Dutch merchant Gerard Van Neck, who was connected socially and commercially with the Walpoles, Thellussons and Neckers. They were involved in international trade, and their names appear in various partnerships. John’s fate is obscure (his partnership with Giles Godin, in New Broad Street, involving the importation of animal furs from North America, was dissolved in 1773, and he seems to have been made bankrupt in 1781, although this may be a confusion with John Jr, see below); by 1784 he was a tenant in Booth Court, Spitalfields (near Brick Lane, and a great descent from New Broad Street).

Mark, who was financially successful, lived for a number of years near the French Church in St Martin Orgar (just off modern Cannon Street in the City). His partnership with Samuel Mestrezat (presumably from Geneva) and Peter Aubertin (from Neufchâtel) was known in particular for the sale of mousselines and indiennes, some imported from Lyon. The firm was London agent for Rey, Magneval & Cie. According to a recent publication, the portraitist Louis-Michel Van Loo, who also had connections with Lyon fabric manufacture, went straight to Liotard & Aubertin when he arrived in London in 1764. The partnership of Mark Liotard, Cazenove & Co was recorded still at 3 Martin’s Lane, Cannon Street as late as 1790, although Mark had returned to Geneva by 1768, where he married Marianne Sarasin-Rilliet (her father was the owner of the property La Servette which was then appended to Marc’s name); the pair were portrayed by Liotard in Geneva, so there cannot have been a family feud. His partner, James Cazenove (1744–1827), was from another Genevan family (although he was born in Naples); he was naturalized in 1778, and left a fortune of £50,000 when he died (but four years later the firm collapsed). Jean-Michel Liotard drew his sister, later Mme Fazy (R&L JML37), but this was in Geneva.

In the next generation, another John (born c.1741) is reported in R&L as Mark’s son, although there is no record of an earlier marriage. This may be a confusion with Mark’s brother. During the artist’s second trip, John Jr was married in May 1773 (although Jean-Étienne does not seem to have attended):