Mlle Thomasset: Liotard’s copyist in needlework

Mlle Thomasset after Liotard, self-portrait, needlework (Vevey, musée Jenisch)

The Thomassets were my entry point for a previous post about Liotard in London (but the surrounding material merited longer treatment), and in particular an erroneous statement in a recent publication that Liotard stayed with them on his first London trip. (He was then located in Golden Square, as that post explained.) They were his neighbours during his second London trip.

All the more confusing because the Thomasset house, 18 Great Marlborough Street (later the premises of Erard, the piano makers), on the north side, is indeed opposite the other “Blenheim Street” (i.e. the alley leading down to Carnaby Street). It lies about 50 metres west of Liotard’s house, on the opposite side.

Mrs Thomasset was a Swiss widow of 62 years of age who had moved to London in 1749 with five of her daughters (aged between 21 and 41), and established a school for young ladies. One of the daughters took up “needlepainting”, or the copying of paintings in embroidery, made popular in London by Mary Linwood (the dates make it hard to determine who influenced whom, particularly since Mary’s mother Hannah Linwood also exhibited needlework, but it seems difficult to believe they both developed this mode independently). Mlle Thomasset made copies of about 20 English and old master pictures, including the Liotard self-portrait exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1773 and acquired by Bessborough (now in Geneva, R&L 447, reproduced in the previous post; her copy is above). They are now in the musée Jenisch in Vevey.

“Mlle Thomasset” (variously identified as Hélène, Julie or Octavie) has been known in Liotard studies for ever: she appears in Humbert, Revilliod & Tilanus’s 1897 monograph as the brodeuse responsible for embroidered copies of pictures, Liotard’s self-portrait among them (the authors however had not seen them); the family’s emigration to London is mentioned very briefly, as is the fact that the pictures had now found their way into the museum in Vaud. Fosca got carried away and declared all the works to be by Liotard, while R&L gave a correct if incomplete account, identifying the artists of some of the other works – among them portraits of Garrick by Gainsborough etc. The discussion is at R&L p. 590 and I won’t repeat all of it: but the family’s London stay is sketchy to say the least.

Here anyway (and with all necessary caveats) is Fosca’s description:

Ils comprennent d’abord ce que l’on appelait autrefois des « têtes d’expression » – un vieillard, une Sibylle, etc. – puis des paysages dans le goût hollandais, assez conventionnels, et ne rappelant en rien son admirable Vue des glacieres de Savoie du Musée d’Amsterdam. En revanche, d’autres sont bien plus intéressants, et nous offrent une traduction très fidèle de portraits que Liotard avait exécutés vers cette époque-là. Ainsi, l’un est une copie en broderie du portrait de l’artiste âgé et sans barbe, le menton dans la main, qui est au musée de Genève et que Liotard exposa en 1773 à la Royal academy. Deux autres montrent un jeune Chinois coiffé d’un chapeau conique, et un domestique en livrée; ils durent être executes d’après des tableaux que Liotard peignit pendant son séjour en Angeleterre. Un portrait de Garrick, qui n’est pas le même que celui de Chatsworth, représente le fameux acteur émergeant d’un œil-de-bœuf, le bras tendu et tenant à la main un livre ouvert. Un autre broderie montre Garrick dans le role du Roi Lear. Il est en pied, dans un paysage, et déclame en brandissant une épée.

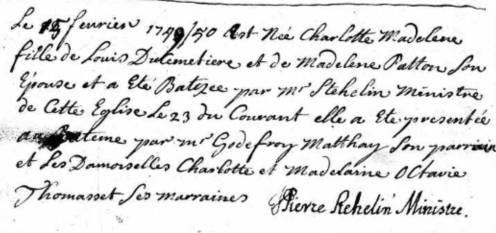

Sir Gavin Rylands de Beer, director of the British Museum and President of the Linnean Society, took up the hunt for the family in the context of Mlle Thomasset’s nephew, the eminent (if short-lived) botanist Edmund Davall (1763–1798). He published a series of short notes in the late 1940s (not cited in R&L) in which he made considerable progress with the genealogy, but still left a number of matters outstanding. Only one of the daughters seems to have married: Charlotte, who married a store-keeper of the Navy slop-office; they were the parents of the botanist. You can see why the name is misspelled so easily from the 1758 register entry:

Charlotte can be found earlier, in 1750, with her sister Madeleine-Octavie, as joint godmothers at the baptism in Leicester Fields Chapel (French Protestant) of another Huguenot (probably from the Genevan family to which the American pastellist Pierre-Eugène du Simitière belonged):

I won’t trouble you with a full rehearsal of the pedigree I have compiled as I was drafting this account: you can see it here. It explains the relationship with Lord Chesterfield’s private secretary (one of his granddaughters was apparently the prototype of the “inimitable Miss Larolles” in Fanny Burney’s novel Cecilia) and quite a number of other relatives with whom confusions have been made.

Among the very few accounts of the school we have Cornelia Knight’s autobiography: she was taken to the Mesdames Thompets [sic] in 1762, aged 5; she dreaded her time there “to a degree not to be described”. (In contrast she greatly enjoyed her drawing lessons from Sir Joshua Reynolds’s sister Frances.) She noted that “the too famous Marat was a Swiss physician and used to visit us at the school.” Dancing was taught by Noverre, brother of the celebrated subject portrayed by Perronneau.

But which of the ten Thomasset sisters was responsible for the embroideries? Davall’s correspondence notes that his remaining living aunts devoted themselves to playing quadrille, from which de Beer inferred that the brodeuse was the sister who died in 1789. But elsewhere she was identified as Hélène. The thirteen siblings were born between 1708 and 1728. There are several Swiss guidebooks which mention (R&L don’t cite them) Mlle Thomasset: Louis Reynier, Guide ds voyageurs en Suisse (Paris, 1791, but written in 1788) writes–

If the 60 age is accurate, this would place her birth at close to 1710 (within a couple of years), assuming she made the Liotard contemporaneously. (R&L do cite Sophie von La Roche, 1792, who says the artist started aged 50 rather than 60.) In any case she was certainly dead before 1795 (R&L give Nagler’s date of 1796), because François-Jacques Durand’s Statistique élémentaire (Lausanne,1795, ii, p. 388) refers to “Feu Mademoiselle Thomasset.”

An examination of the girls confirms that the name of Hélène, which R&L put forward with a question mark but is the name favoured in the various sources, perfectly fits the information we have, and supports Reynier’s version. Two further pieces of information confirm this. One is Hélène’s will:

Je donne a mon neveu Edemon Davall aprai la mor de toutes mes soeurs mes tablaus en ca qui setablice den ce paï autremen mes soeurs en disposerons a leur gré…

One hopes that she was not responsible for teaching grammar or spelling at the school. But she has also signed one of the needlepaintings, on the letter held by the footman “A Mademoiselle/Helene Thomasset/Chez Elle”:

Mlle Thomasset, A footman with a letter, needlework (Vevey, musée Jenisch)

If this is Fosca’s “domestique en livrée”, I doubt whether it was done in London in view of the language of the address; but the liveried black servant may remind us of Baron Nagell’s, in the Ozias Humphry pastel now in the Tate. Perhaps someone can identify the livery (hint: a footman’s livery is supposed to reflect the colours of his master’s arms, so they should be azure, charged with or).

Hélène-Louise Thomasset (Agiez 11 February 1710 – Orbe 11 March 1782) has left little further trace of her existence beyond the pictures. I can however add some information about the sisters’ finances, culled from the archives of the Bank of England. Starting in 1760 Hélène bought £200 of the Bank of England’s 4% Annuity 1760 (one of the bank’s perpetual stocks later known as Consols):

Courtesy of the Bank of England Archive

Her sister Octavie did the same the following year; she was then living in Soho Square. By 1766 the holdings had been transferred into a joint account in the names of Hélène-Louise and their eldest sister Anne-Jeanne-Louise “Nanette” (1708–1792), who was living with Hélène in Great Marlborough Street throughout. By 1773 their holdings amounted to the sum of £3600, and were growing at the rate of about £500 a year. (Some care is needed with these sums, as the Bank of England ledgers record only nominal amounts rather than market prices, but yields remained fairly constant between 1762 and 1773 at around 3½%. The sisters may also have had holdings in other stocks.)

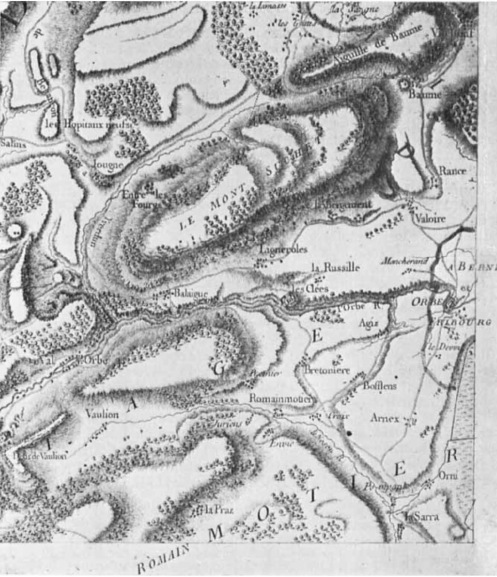

By 1777 the sisters (Mrs Thomasset had already died, at an unknown date) decided to return to Switzerland. On 26 March 1777, through their cousin, they purchased (while still in London)

une maison avec une terrasse devant, une grange, une écurie, une cour avec un bûcher deux jardins en deux terrasses, le tout contigus et battis à neuf et tel qu’il est situé dans la ville d’Orbe à la rue dite la Boucherie et encore une vigne derrière la maison d’environ quatre ouvriers.

Thus the Thomasset family, who were reported as leaving Switzerland because they were poor, went back comparatively rich, as is confirmed in a letter from an Irish traveller to Switzerland, Blayney Townley Balfour (several Jacobite pastels by La Tour and Hamilton were at Towneley Hall), who wrote home to his mother in 1788–

I have been but once out of this House at any Parties. It was at a Madam Thomasy’s who once kept a very famous Boarding School in London & is with a couple of her sisters retired to spend the Remainder of her Days in Swiss opulence upon £500 a yr. That is no inconsiderable Income here & they are one of the first Families here. There lives in the House with them a nephew of theirs, a Mr Daval, an Englishman…

Here, by way of contrast with London, is a map showing the house at Orbe where Hélène died (her sister Catherine died two days later), a mere 500 meters from Agiez (spelt Agiz in the map) where she was born:

Google Earth confirms that little has changed:

Some ten years after Hélène’s death, as we learn from Davall’s letters, Lady Spencer, the Duchess of Devonshire and Lady Duncannon visited Orbe during their stay in Switzerland in 1792. They all developed an interest in botany, but the Duchess preferred mineralogy. We are not told whether the ladies recognised Liotard from his portrait in needlework.

All this merely confirms what we knew already: that the Huguenot links between Switzerland and London provided a network in which Liotard and his clients moved comfortably.

One final aside, while we are on the subject of botany: another Liotard, Pierre (1729–1796), from near Grenoble, was for a long time rather more famous than the artist, and today is still known for his friendship with Rousseau (see this earlier post) – and for being killed by the fall of a stone sphere decorating the entrance to the Jardin des plantes in Grenoble of which he was in charge. Any relationship to the Genevan family would be distant.

Sources and notes

The best source on the family is Benjamin Baudraz, “Les Thomasset”, Bulletin généalogique vaudois, 2005, pp. 63–134, but as there are no copies in England I wrote most of this post before I was able to obtain it. The other sources are R&L; Survey of London; Fischer 2007, with Townley Balfour’s letter; Humbert, Revilliod & Tilanus 1897; Fosca; Gavin Rylands de Beer, “Edmund Davall, F.L.S., an unwritten English chapter in the history of Swiss botany”, Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London, CLIX, 1947, pp. 42–65; de Beer, “Thomasset”, Notes and queries, cxciv, pp. 445f; “The Thomassets’ school”, Notes and queries, cxcv, p. 54; Autobiography of Miss Cornelia Knight, lady companion to the Princess Charlotte of Wales, 1861; E. J. Burford & Joy Wotton, Private vices, public virtues, 1995, pp. 143ff (for Mrs Goadby). The pedigree is drawn from dozens of sources; for the sisters’ dates, the list on familysearch.org was unusually comprehensive and apparently reliable, unlike earlier sources. I am grateful to the Archives of the Bank of England for the unpublished entries in their ledgers. For Mary Linwood’s portrait of Napoleon, see here.