Liotard, Jean Dassier (Geneva, mAH)

In two articles in the Burlington Magazine, in 2002 and 2003, François Marandet radically transformed our knowledge of the early years of the two best-known pastellists of the eighteenth century, Maurice-Quentin de La Tour and Jean-Étienne Liotard, with the publication of their apprenticeship contracts. As it happens, they were born just 20 months apart, and both came to Paris for their training. But while La Tour followed the conventional path of a Parisian artist starting with apprenticeship at the age of 15, leading to eventual membership of the Académie royale, Liotard’s formation was anything but conventional.

A comparison between the La Tour (1719) and Liotard (1723) contracts, with Claude Dupouch and Jean-Baptiste Massé respectively, at first sight suggests they describe the same legal relationship, albeit La Tour’s is for a term of six years (Liotard’s three), and La Tour has to pay a premium (Liotard did not). The wording is of course a standard form, and large parts are essentially identical, so that, for example, the master “promet montrer [the pupil] tout ce dont il se mêle et entremêle dans l’art de la peinture, le nourrir, loger, coucher, blanchir, chauffer et le traiter humainement comme il appartient”. But there is one crucial distinction in the wording which Marandet did not notice (nor anyone else as far as I am aware, although R&L noted the absence of the word apprentissage), and which means that Liotard’s contract was not one of apprenticeship at all. Unlike the La Tour contract, Liotard is described as an “alloué”. The word is used four times in the document; there is no mistake. The legal arrangement it describes is not one of apprentissage, but of allouage.

Since the terms are otherwise similar, you might think this was a distinction without a difference. But that is not the case. An allouage was an arrangement (quite common in Paris at the time, among many trades) in which a worker, often (but not always) a compagnon or journeyman who had completed an apprenticeship already, was hired for a term. (So the scope for differences of opinion as to the role of the pupil was considerable, and may partly explain Liotard’s famous indignation with Massé’s teaching.) They could be older, like Liotard (who was then six years older than La Tour had been), or not. In about half the examples studied by historians who specialise in such things, no premium was involved; but in others the premium might be similar to that in an apprenticeship. But the crucial difference was that the arrangement did not lead to maîtrise, i.e. the right to practise independently.

How much of a problem was this? Massé was a member of the Académie royale. Under a little known arrêt du parlement de Paris of 14 May 1664, pupils of academicians who had completed three years as an “élève” were permitted to claim maîtrise in any town in France, including Paris. But the Procès-Verbaux of the Académie royale show that early cases of use of the 1664 decree were minuted, to authorise the grant of the necessary certificate; no such minute appears for Liotard, and the practice may simply have been abandoned. There is no record as to exactly when Liotard joined the Académie de Saint-Luc (as is so often the case – although of course we know he exhibited there much later), an alternative route to having the right to paint professionally. So we do not know on what basis he was able to set up in business after leaving Massé. We still know less about such things than we would like.

One of the revelations in the contrat d’allouage is in the attached letter of authority from Liotard’s father. In it he mentions two men, “Ledouble” and “Geurain”, from whom he had learned about his son’s proposed engagement with Massé; Marandet speculates that the introduction to Massé was facilitated by them, but does not further identify either.

“Geurain”, I suggest here, is surely a misreading of Pierre Gevray (1679–1759), a graveur from Geneva who established himself as a marchand in Paris where he would have retailed the watches that he had engraved. In 1729 he married, at Coppet, Jeanne de La Roche, possibly related by marriage to Liotard’s teacher Daniel Gardelle. (Gardelle was born in 1679, not 1673, an error that continues to appear frequently in the literature.)

Roethlisberger & Loche do mention Le Double, on p. 239 (omitted from the index), as a Genevan and an associate of Dassier. Jacques Le Double (1675–1733), graveur du roi privilégie suivant la cour, had in fact sublet an apartment from Massé, place Dauphine, just six months before Liotard’s contrat d’allouage; he did so with another engraver, Antoine-Charles Robineau (his son Charles-Jean Robineau was a portraitist and engraver who worked in England). Le Double’s association with Dassier was important, as we can see from a notice in the Journal historique et littéraire for June 1724 (p. 397), advertising the suite of 70 medals of famous Frenchmen in science and the arts engraved by Dassier and sold in Paris by Le Double. A permanent resident in Paris, Le Double nevertheless continued to pay taxes in Geneva. He married a Catherine Fradin in 1721, and she and four minor children were alive when he died in 1733. All four returned to Geneva, where they married into the Tremblay, Michaud, Pasteur and Bouvier families; the son, Jean-François Le Double (1729–1788), was a watchmaker in Geneva.

Liotard’s own connection with Dassier is of course well known (even on this blog), principally through the wonderful pastel of him now in Geneva (R&L 10, reproduced above) whose exact date remains uncertain. Its achievement is all the more remarkable when one investigates what other pastellists were doing at the time: the demand had been created by Vivien and Rosalba Carriera, both of whom had left Paris by the time Liotard arrived; Lundberg was the main practitioner before the emergence of La Tour, but that is another story. (So is the response of the French establishment to Liotard’s later work, the focus of my essay in the Liotard 2015 exhibition catalogue.) Less is known about Liotard’s possible relations with Dassier’s son, the medallist Jacques-Antoine (1715–1759). Born in Geneva, he trained in Paris from 1732, and must have overlapped with Liotard. Both artists went to Rome in 1736. Dassier fils worked in London 1741–45; the series of English profile medallions he made (many were copied by other artists) may have been among the influences for Liotard’s curious cameo profiles in which the images seem to display more life than a medal should.

A puzzle surrounding Liotard’s aspiration to join the Académie royale concerns his Protestantism. Massé himself was a Protestant (in a somewhat cryptic passage in his nécrologie, it is suggested that he was not particularly devout – “sans aucun fanatisme”), and this served as no barrier to his full membership: but there is no record of any special dispensation in the Procès-Verbaux, and it may be that he abjured for these purposes (Jal however states that “le Régent permit qu’on ne tînt pas compte des ordonnances de Louis XIV, et l’Académie passa outre”). And perhaps Liotard would have done the same. Otherwise, as the records of the Académie make clear, the Protestant artists – Boit, Lundberg, Schmidt, Rouquet and Roslin – were all admitted by specific royal command. As Vaillat noted, when Liotard was working for the court on his return to Paris in the late 1740s, there would have been no difficulty in obtaining the same consent had the establishment wanted him. But in the early 1730s the hurdle may have seemed higher to the artist.

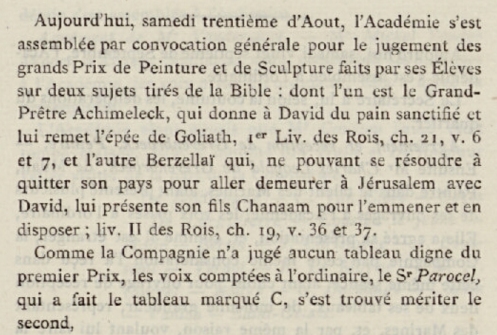

In fact it was in 1732 (not 1735 as appears in all sources to 2015) that Liotard submitted a history painting (known only from an old photograph, below) for the prize competition at the Académie royale, the topic that year being Le grand prêtre Achimelech remet à David l’épée de Goliath (bafflingly no one seems to have spotted this until now: R&L conclude that he must have submitted this work to for the Académie de Saint-Luc, selecting the topic himself since they thought there was no record of the subject being set by the Académie royale, but the matter is easily discovered with the Procès-Verbaux). He was already far older than most competitors: Boucher, Natoire, Pierre, Carle and Louis-Michel Van Loo all won under the age of 21).

R&L also note that the composition is a long way from the Aert de Gelder picture of this subject in the Getty. But other illustrations of the story were available as prints at the time, and might perhaps have provided Liotard with a visual vocabulary. One is from David Martin’s 1700 work, Historie des Ouden en Nieuwen Testaments, in two volumes with 285 illustrations, many by Bernard Picart (left). The other was from Caspar Luiken’s engraving for Historiae celebriores Veteris Testamenti Iconibus representatae…, issued in 1712, with a similar number of plates (right).

Liotard did not secure a prize with his rather wooden religious piece: the Académie (Procès-Verbaux, 31 août 1732) “n’a jugé aucun tableau digne du premier prix”, and awarded only a second prize, to Parrocel:

Trivas, one of the last authors to have seen the Liotard painting, commented that “La composition est théâtrale, les gestes affectés, l’ensemble vide.” To judge from the surviving old photograph; it is unnecessary to postulate Massé’s enmity for the Académie’s reaction, as Marandet has suggested; as the Procès-Verbaux reveal, Massé did not even attend the session in which the prizewinners were selected. It should also be noted that Massé kept a work by Liotard (R&L 8, now in the musée Patek Philippe, below) at the time of his will, many years later. This will is extremely long, and while Marandet mentions the work, he omits the context. The Liotard was one of a number of miniatures owned by Massé’s sister-in-law in London (Mme Jacques Massé, née Marie-Madeleine Berchère), and sent to him “pour les raccommoder”, being all “en très mauvais état”. Massé’s will goes on: “Il y a bien longtems que ces divers ouvrages sont entre mes mains et que non content de les avoir rétablis…”. No. 8 was “mon portrait en émail copié par le sieur Liotard, d’après un original peint par moy-même.” It is then referred to several times as to be sent to his niece Elizabeth, Mrs Jones, as R&L note. The group of miniatures must have been in a fire at some stage, as the damage to the Liotard suggests. When it was in the collection of Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Dacres Olivier (1850-1935), Massé’s great-great-great-great-nephew, a description said to have been written by Massé was reported as being on the back (not mentioned in R&L):

Jean Baptiste Massé. Il n’a plus actuellement qu’un ombre obscur et fletri de ce portrait qu’il n’a peine se faire peindre sous ses yeux que pour completter la collection de son aimable belle soeur d’apres son Portrait fait en son jeune age que l’on trouvoit ressemblable, Tel est le sort de notre hu(manite).

Reading all of these references together makes it very hard to find hostility to his former pupil. (There is an anonymous pastel copy of another Massé’s self-portrait – see the Massé article – but the technique is not Liotard’s).

None of these trouvailles fundamentally changes our picture of Liotard, but I hope they serve to flesh out some of the sketchier areas of his life and work and situate him in the artistic world in which he developed.

Postscript (19 January 2016): Jean-Michel Liotard in Paris

It is all too easy to overlook the achievements of Liotard’s prodigiously talented twin brother Jean-Michel (1702–1796). R&L devote a separate section to him, and include a catalogue of his engravings and drawings (44 numbers). Jean-Michel followed his brother to Paris in 1725; ten years later he moved to Venice. During that period he worked for the engraver Audran (as to which one, see R&L), and engraved six plates after Watteau for Jullienne. Few documents are known (we do not know what form of contract he had with Audran, but it may well be one of allouage), but I found this account of his earnings over four years in the V&A archives (where it is filed under Jean-Michel Liotard 1836-1911). It indicates how much a talented alloué could receive: some 600 livres per annum for four years. The addressee is unknown, and the “4 desseins contrepreuves” is the only indication of the nature of the work.

Sources and notes

For full references, go to R&L and the Liotard articles on pastellists.com. Full publication details for Marandet 2002, Marandet 2003b &c. are in the Bibliography, while the Prolegomena has more (with literature) on the in the Paris institutions (for allouage, see Thillay 2002) and on the demand for pastel created by Vivien and Carriera. William Eisler, The Dassiers of Geneva, i, 2002 and Campardon is useful. The Le Double lease is in the Archives nationales, MC, CXVIII/337, 26 octobre 1722: “Bail pour neuf ans, en sous-location, par Jacques Ledouble et par Antoine-Charles Robineau, maîtres graveurs, à Jean-Baptiste Massé, peintre de l’Académie royale, du premier appartement de deux maisons contiguës sises place Dauphine, appartenant au sieur de Creil, dont l’une a pour locataire principal ledit Ledouble, l’autre ledit Robineau, moyennant 300 livres de loyer annuel à chacun des bailleurs”. His association with Dassier: Journal historique et littéraire, .vi.1724, p. 397. The Massé description when in the Olivier collection is in Lart’s Huguenot Pedigrees, London, 1928, ii, p. 64.

News this morning that the FCA has abandoned its review into the culture of banking is surprising only in the fact that it has been announced. All of these reviews have had little real impact on the actual conduct of retail or wholesale banking, apart perhaps from the nuisance value of having to set up ring-fencing: but that too is being quietly watered down so that it will have modest impact on profits. The one review no government has threatened (and no opposition has called for) is a proper investigation into how banks actually make money: this would risk exposing the inherent vice of a system with, at the heart of its corporate side, almost total dependence on zero-sum-less-bonuses trading, and for retail, equal addiction to products which customers don’t understand.

And yet an increasing numbers of intelligent economists as well as journalists are recognising that in a mature, competitive market, banks are driven to cheat to survive. PPI tells the story, but there are countless other examples where banks and their customers form bargains in which the sources of profit are the asymmetries of information or other exploitations of customers’ cognitive errors.

You may say caveat emptor. But that isn’t what the politicians say. It has long been recognised that it is fundamental to the workings of society that banks be held to a higher standard that a fruit trader in a market stall. The position is some way short of the fiduciary role that a lawyer or professional advisor has, but (at least in theory) is considerably more burdensome than for the street trader. And it is imposed both by statute (for example, the Unfair Contract Terms legislation, which is supposed to stop big businesses hiding outrageous terms in small print they have drafted) and by regulation. Since everyone knows that banks are adept at getting round specific rules, regulation comes with the FCA Principles which are supposed to reassure consumers that they will be treated fairly.

Here are some of the most relevant ones:

Principle 6 (customers’ interests) A firm must pay due regard to the interests of its customers and treat them fairly.

Principle 7 (communications with clients) A firm must pay due regard to the information needs of its clients, and communicate information to them in a way which is clear, fair and not misleading.

Principle 8 (conflicts of interest) A firm must manage conflicts of interest fairly, both between itself and its customers and between a customer and another client.

These are clearly modelled upon the English common law which imposes upon fiduciaries onerous rules such as never having a conflict of its own interests with those of a customer (“no conflict”), nor having a duty to one customer in conflict of that owed to another (“undivided loyalty”), and not profiting at the expense of the customer (except reasonable professional fees) (“no profit”).

But do the principles work? Or rather, are they applied?

In practice, no. The FCA and the Financial Ombudsman show an extraordinary reluctance to invoke them when banks are caught behaving unfairly (or cheating in everyday language). And when the regulators show signs of toughness, they are sacked.

First of all, what is fair? It’s not a term with a statutory definition, but I’ve written before about Lord Sumption’s judgment in the Plevin case. There it seems the regulators thought that as no specific rule was broken, the banks should be allowed to get on with it; however the judge had no difficulty in deciding that the consumer had been cheated because she hadn’t been told about the outrageous amount of her insurance premium which was being paid as commission without her knowledge. The only difficulty was how to bring this consideration into the decision; in that particular case a little known provision of the Consumer Credit Act was brought into play. But for most consumers the courts have no such power, and they are dependent on the Financial Ombudsman to enforce the general principles – i.e., not at all.

And from the FCA’s current consultation on how to respond to Plevin, they are determined to keep it that way. There is no suggestion that Plevin ideas should be allowed to sully any area of consumer finance where the specific CCA provision was not engaged: on the contrary, the consultation is about how to limit the fall out from such dangerous thinking.

But Lord Sumption’s principle, that the relationship cannot be regarded as fair if the customer is kept in ignorance of some term knowledge of which would lead a reasonable person to walk away from the deal, seems to me to be no more than the FCA principles imply. Such a term is clearly something the consumer needs to know, and not informing her offends each of the principles 6–8 cited above.

You can easily think of similar cases where this applies. When a bank pays interest on a deposit account, it is obliged to tell you or advertise if the interest rate drops by more than a certain amount relative to base rate: that’s a specific rule, breach of which should lead to a successful complain to the Ombudsman. (Of course it doesn’t, even then: in one case where a bank failed to advertise such a reduction, the Ombudsman rejected my complaint because I couldn’t prove that I would have seen the advertisement which hadn’t appeared; as usual I had to issue court proceedings to obtain redress). But what happens if a bank holds your rate where it is, the Bank of England continues to ignore upwards pressure on rates and to remain competitive the bank introduces a new account, identical except that it pays twice as much interest? They know that you would switch if you knew, so they don’t tell you.

Is that in accordance with your information needs and the other principles? Well, yes, according to the FOS: anything else would interfere with the banks’ legitimate right to cheat you. And if you point to the specific rule that says that banks go through certain procedures to monitor conflicts of interest (these are specific rules), they say it isn’t a conflict of interest. Indeed according to one ombudsman, putting the bank’s profit before the customer’s return can’t be a conflict of interest: “this particular principle [is] intended…to deal with issues arising from the potential abuse of business relationship [such as] where a mortgage intermediary passes large amounts of business to a lender because they have a relative working at that lender.” In other words he reduces FCA Principle 8 to the common law “undivided loyalty” rule, rather than recognising that it also embeds the simple “no conflict” rule. And it flies in the face of the actual wording of Principle 8 which includes the phrase “both between itself and its customers”.

Now many of you will think that I’m asking too much from banks by asking them to be held to Lord Sumption’s principle. But perhaps the real focus of my concern is not where the level of consumer protection is set, but the hypocrisy with which the FCA Principles are held up as shining examples of effective regulation where the practice is of ignoring their literal import at every opportunity. If the principles overreach where parliament wants to set the limit, they should be rewritten, not undermined. There is enough disrepute already in this industry.

Well, we might want to throw them at the author (John Hawkesworth) of this drivel which appeared in the Gentleman’s Magazine as the Poetical Essay for May 1750 (I have spared you the lengthy text). But it serves to illustrate how long it has been known that moving pastels is risky. I’ve written about this in far greater detail (and with copious references to the literature) in Chapter V of my Prolegomena, but it may be worth summarising the key points of the debate between the risk-deniers and the nay-sayers. We are united in wanting to find the answer.

Well, we might want to throw them at the author (John Hawkesworth) of this drivel which appeared in the Gentleman’s Magazine as the Poetical Essay for May 1750 (I have spared you the lengthy text). But it serves to illustrate how long it has been known that moving pastels is risky. I’ve written about this in far greater detail (and with copious references to the literature) in Chapter V of my Prolegomena, but it may be worth summarising the key points of the debate between the risk-deniers and the nay-sayers. We are united in wanting to find the answer.

Everyone knows that pastel is fragile and that moving it is difficult. 2015 has seen a number of international pastel exhibitions (Karoline Luise in Karlsruhe, Vigée Le Brun in Paris, soon to move to North America, and Liotard in Edinburgh and London come to mind) which, to judge from press reports, may have left some people thinking that the problems have been solved – although in fact pastels have been moving to international exhibitions for many years.

As I recount in the Prolegomena, an important first step in the scientific research arose with the 1989 Degas exhibition in Liverpool and Glasgow where significant concerns were raised. An international association of most major museums concluded in 1995 that “unfixed pastels are usually too fragile to travel.” But by 2004, when a number of exhibitions were held to celebrate La Tour’s tercentenary, pastels were on the move again; only for another report to conclude that all loans of pastels should be prohibited, without exception. That remains (with very rare exceptions) the policy of the Louvre and the museums with major pastel collections in Saint-Quentin, Amsterdam, Dresden and Geneva. As it happens it is also my policy since 2004 (but not before). But not everyone agrees, and I can see that there is a defensible position to take in arguing that some exhibitions are so important that the risks – maybe even the certainty of some minute level of damage – are worthwhile. But that’s a somewhat different position than suggesting that the problems have been solved. (And I am of course aware of the lengths to which organisers go to minimise risks.)

A great deal of research has gone into the logistics of moving art, but I want to give you an idea of what the issues are for pastel and how far we are from having comprehensive answers or a general consensus. Specifically I want to highlight some counterintuitive results from the published research. Do please contact me if you are aware of any relevant work I haven’t covered (in the Prolegomena – this blog post is only an informal summary).

Perhaps the most obvious point is that art can be damaged, even by surprisingly small levels of shock or vibration. When the British Museum carried out construction work for the Great Court development, careful monitoring found that vibration could be transmitted far further than the standard decay model predicted. And it also found that objects with painted surfaces could lose pigment with shock levels as low as 0.2g – far lower than anyone had imagined. Admittedly these had pre-existing weaknesses – but of course it is the nature of pastel to have what insurers call “inherent vice” (which means that the question of shipping them safely may have a financial angle for owners as well as the purely artistic question in which we all have a share). You simply can’t lift a pastel off the wall and package it however carefully without exceeding that level.

But of course you will say that this is nonsense: if that were true, no eighteenth century pastel would survive today. And (if you are in the trade) you ship them all the time, and no damage is ever visible…well, of course, there was that case… – but that was in poor condition. And better not raise…

So yes: pastels can suffer a higher level of shock than 0.2g with no visible damage – sometimes (maybe even most times). (Those that can’t are already ruined, and probably disposed of to release the frame. A great many eighteenth century pastels have vanished.) And of course there are the cases no one wants to talk about (me neither: I’d win no favours for identifying specific works as seriously compromised – so there are no photographs in this post): there is a built-in cognitive error compounded by an anti-disclosure bias surrounding the information.

But also the fear is that you can’t tell from the appearance what’s going on underneath. Damage may not be reported simply because it isn’t visible. Your picture comes back from the exhibition: it looks a little strange, perhaps, but when you compare it with the photograph you can’t spot any area of fallen pigment, so you must just be mistaken. Better not make a fuss: no insurer will pay up.

Here’s where the fruit come in. The great thing about a bruised peach (a real one, not a Liotard nature morte) is that it will reveal its hidden abuse fairly rapidly. And the supermarkets have invested a vast amount of money in research in how to measure and minimise shock and vibration in the transport of perishable goods. So we know for example that vehicles with air-ride suspension are smoother than those with traditional leaf-spring suspension (unless the air-ride mechanism isn’t working properly, in which case the ride is worse: the compressors used to drive the suspension can themselves cause vibration). But we also know that the grapes at the top of the box fare worse than those at the bottom, even though the latter suffer far greater compression: so repeated small impacts can be worse than fewer stronger ones.

We also know that the shock and vibration behaviour of different forms of transport is counterintuitive. To take an example where opinions remain strongly divided, most studies show that, at least as regards measurable vibration, road freight is astonishingly far worse than air (and marginally worse than rail, but the rail figures aren’t consistent). But the big problem with air travel is that you aren’t allowed simply to place your packing case directly in the hold: it has to go through the cargo handling areas, where it will drop off the end of a chute, experiencing shock levels in the range 6–10g (and much higher if it is a case small enough to be lifted by hand, when dropping is highly probable). (Of course good packaging will reduce the impact on the pastel itself, perhaps by 60%, maybe more.) And that’s not to mention the shocks on the “dollies” which carry the boxes out over the tarmac – and this to owners who carry out experiments in which the difference between pneumatic and solid rubber tyres on trollies used to move pastels within a museum is thought significant.

So if you have to choose between air and road transport, you have to balance the risk of say half a dozen shocks of 8g with say 50 hours of vibration at a mean acceleration of perhaps 0.5g at a frequency of say 10Hz, i.e. occurring ten times a second. Obviously distance matters: the hazard from road transport is proportional to it, while if vibration during the flight is as low as suggested, “ce n’est que le premier pas qui coûte.” But how do you calculate the trade-off?

Fortunately mechanical engineering again has a methodology. Here is a so-called S-N curve, in which you plot on the y-axis the stress which causes failure for a specific number of cycles of a repeated shock. If there is just a single or a few cycles (e.g. at N1), the stress required will be high; but repeating a lower stress many times may also cause failure (e.g. at N2): hence the general shape of the curve.

The key question for any material is how the long tail behaves. Does it level out above zero stress, so that if the stress is below that level (the so-called fatigue limit), it doesn’t matter how often it is repeated? And if so, are you sure that the fatigue limit itself will not be exceeded?

This is how many engineering problems (notably in air crash analysis) are approached. They are dealing typically with simple materials such as homogeneous metal alloys. The same methodology is being applied in painting conservation, and to pastel by a group currently working in the Rijksmuseum, but as you can easily imagine the work is immeasurably more complicated. We don’t yet know if there is a fatigue limit for pastels (nor whether they are really like wings or pears), and so we can’t really answer the “road or air?” question. (Except by: no.)

A good deal of information has been gleaned from mounting accelerometers in different locations in various types of lorry. (I’ve also done this in my car, which I can report produces figures considerably better than air-ride lorries: but I’m not offering a competing service.) We can identify which types of packaging minimise certain frequencies of vibration – and note that some unexpected resonances can occur which mean that solving one problem may create another. We can establish (and most people agree) that for road transport the vertical shocks will be higher than the horizontal ones (either in the direction of travel, or from side to side). But does it follow that a pastel is best travelling flat? Most (but not all) museums think so; but I’m not sure there is much evidence comparing the forces required to lift pigment from a pastel shearing it sideways rather than propelling it at right angles to the surface (one paper that investigated this used modern samples that were not mounted on canvas, a vital part of the problem). And horizontal travel for any support that has lost tension increases the risk of the pastel touching the glass. And so on.

What is clearly important is for more information to be gathered and shared openly. If someone comes up with a magic carpet, let us gain consensus for its use. If a practicable fatigue limit for all pastels against all risks can be established, it will only be generally accepted when the research is published in scientific journals. Until then few will want their original eighteenth century examples tested to destruction; but even when that is done, my fear is that we will find that no two pastels are the same. All metal alloy specimens resemble one another, but each pastel is inherently vicious in its own way.

Bloggers are an opinionated lot: it goes with the (non)-job. And normally I know what I want to say, or at least what direction I’m heading, when I start. But on this occasion I am bewildered. I’d love to be completely enthusiastic about the newly reopened Europe 1600–1815 galleries at the V&A, as I have a soft spot for this institution. You may not know that the V&A is the national museum responsible for pastel – an unwanted hot potato passed by the National Gallery (they of course kept the best paintings, so for the most part the pictures in the V&A collection are second rate). It’s also the only national museum which I can reach any day of the week by car in 15 minutes, and that alone counts for a great deal when my visits to other museums are overshadowed by physical discomfort exacerbated by public transport. If you’re one of those who thinks everyone should be forced to cycle everywhere, just remember some of us can’t.

Bloggers are an opinionated lot: it goes with the (non)-job. And normally I know what I want to say, or at least what direction I’m heading, when I start. But on this occasion I am bewildered. I’d love to be completely enthusiastic about the newly reopened Europe 1600–1815 galleries at the V&A, as I have a soft spot for this institution. You may not know that the V&A is the national museum responsible for pastel – an unwanted hot potato passed by the National Gallery (they of course kept the best paintings, so for the most part the pictures in the V&A collection are second rate). It’s also the only national museum which I can reach any day of the week by car in 15 minutes, and that alone counts for a great deal when my visits to other museums are overshadowed by physical discomfort exacerbated by public transport. If you’re one of those who thinks everyone should be forced to cycle everywhere, just remember some of us can’t.

But however you get to South Kensington, it’s only a few steps from the front entrance of the V&A to the gloriously theatrical white marble staircase which leads down to the new galleries. It’s so long since they’ve been shut you may have forgotten the old basement with the Jones collection: I remember it with some affection, although it was certainly dingy, institutional and “tired”. So what have they done – with some £12.5m of public money?

The first sight brings immediate pleasure. As you go down the steps, as into a subterranean cave, the space opens into an exciting vista dominated by the V&A’s magnificent Bernini Neptune – finally in its rightful space after years of pretending to be British. Or is it? After all when Bernini made it 400 years ago it was intended for the open air in Rome. I can’t help feeling that the daylit Gallery 50, where it resided until some ten years ago, was not a better compromise for this ton of marble which epitomises the Baroque and, for me, yearns for the sun:

For it has landed in the first (or last? a curious minutia is that that the rooms are numbered backwards, both chronologically and geographically: this is room 7) gallery in the new suite.

The immediate impression is of architect-led lighting: VERY dim – my light meter barely registered any ambient light, showing an incredibly low 2 lux in many places, with objects dependent exclusively on directional illumination. (Perhaps this is because I visited on a dull December afternoon: the press release claims that natural light has been let in. Note that my camera “corrects” all this.) For the most part this is well done (there are few distracting reflections, although I have left one oval track in the photo below); and as I have argued before, this theatrical approach has some merit when the objects themselves are not the prime attraction.

For while the V&A has many treasures and large, comprehensive collections of objects of specific types, museology has long abandoned any interest in systematic presentation of anything. And – unless you’re a specialist in mediaeval matchboxes or baroque biscuit-tins – that will be a great relief. So the purpose must be to present things which will grab the attention, inform and educate (in that order): and the audience should be as broad as possible, from the schoolchild and tourist to the intelligent tax-payer, and even perhaps the scholar in an adjacent field. With such impossible constraints compromises are inevitable.

You’ll have noticed that I too have abandoned any systematic approach to the structure of this blog: some random thoughts with a scattering of images to give you a better idea of what you can see when you go. Here’s what you find in one gallery:

You’ll notice immediately that the objects are not just not lined up in serried ranks, but are mixed as widely as you can imagine. This is not so much the cabinet of curiosities as the Old Curiosity Shop. Within a few yards you find paintings, prints, miniatures, metal work, musical instruments, wax models, lots of Boulle (only natural history specimens seemed lacking – but perhaps I overlooked some). And textiles. Indeed (perhaps this should not surprise, as the lead curator is a renowned textile scholar) it is the textiles that come out of this display the best. They are given the room they need; the lighting works brilliantly; and a sense of the importance of wall-hangings in draughty seventeenth-century castles is admirably conveyed. Here is the Gobelins Infant Moses after Poussin:

Costumes are also a strong point in the V&A’s collections, and well displayed in other galleries. A few token outfits in the final galleries looked a little forlorn in their glass boxes: some of the architects’ inspiration seemed to have evaporated by this stage, and the downside of raising the ceiling was the exposure of some rather institutional fittings that one might have preferred to hide.

But elsewhere there is plenty to delight the eye. A glass clavichord has all the glitter required to offset so silly an idea. The Georges Jacob bed is gorgeous (the press release misspells his name). Graf Brühl’s ceramic table fountain is spectacular in its Dresden pointlessness: a video (mercifully with no sound track) is on hand, but I passed.

The recreated historical interiors are wonderful means of firing the imagination, even (especially?) when quite small: my favourite is Mme de Sérilly’s cabinet. But I seem to remember an even greater childish delight when you came across it in the old basement suite: perhaps faulty memory, or perhaps there was something after all in the institutional submarine ceilings that enhanced the fantastical potential of these little confined spaces.

But what of the educational value of the presentation? (Incidentally there were sadly few people there during either of my visits.) I’m certainly not a subscriber to the idea that museums ought to take over the role of schools in teaching the history of Europe in a thousand objects. But I suspect there are lots of parents who think that that is at least part of its role. If so I suspect they will be disappointed. Perhaps if one reads the labels more diligently than I did…

The dominance of France does however clearly emerge, quite rightly. But here is the rather curious display explaining the role of the Académie royale in the development of the arts:

You will notice the print after Leclerc, and you may well want to explore this further with the V&A’s own collection database as the print raises a number of questions – e.g. why is the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture described as the Académie des sciences et des beaux-arts? Incidentally beaux-arts and arts are not synonymous; and the collection database can’t make up its mind whether this reproductive print is by Cochin père or fils. (It’s the former; and Leclerc’s allegory is a bit too complicated to explain here.)

But there’s a much more significant disappointment with this display, one right at its heart. And it’s disappointing for intellectual as well as visual reasons. First you need to understand the geography of these rooms: the enfilade occupies the Cromwell Road frontage west of the main entrance, and then turns up Exhibition Road. The middle room, the south-west apex of the building (as I know only too well from a successful appeal to a parking penalty based on road markings inconsistent with official order), is the apex, cornerstone, lynchpin, vertex not only geometrically but historically and intellectually. For this is the room dedicated to the Enlightenment. The V&A have had similar problems in the same room on the upper floors: within the British suite, what was an open space with a few armchairs and some books has now been fenced off as a sponsored “learning area” – with a large-screened TV and rows of chairs. So what would they do below?

I don’t know why it was felt necessary to do anything other than a conventional display of excellent Enlightenment material. I had hoped that this would be an opportunity to present some of the pastels which the V&A keeps in Blythe House: the extraordinary Liotard of Sir Everard Fawkener which you can see in the Royal Academy for another few weeks would surely (if suitably reframed) have told a significant part of the story, and the two Nattier pastels will probably never get a better opportunity to see the light of day (or as close as the V&A will allow). But no. Instead we get a few good portrait busts scattered around the corners of the gallery to leave room for an INSTALLATION.

What were they thinking when they commissioned this? Its dominance in a small room makes it impossible to photograph in its full meaningless invasiveness. It is not so much a spacecraft from another planet as a giant pumpkin built by Ikea – but not just for November. To compound the intellectual vacuum it creates, a wall text has an inevitable reference to the Panopticon. Appropriately the equally inevitable bust by Messerschmidt that oversees all this is supposed to represent “strong odour”, an expression of profound disgust. I’ll leave you with that.

Or is it (4)? There seems to be no end to the stream of trivia and minutiae that can be unearthed about this fascinating artist (you can search with the box on the right the numerous posts here, at least ten since May, and many more have been silently incorporated into the online Dictionary articles) – the hunt no doubt stimulated by the current Royal Academy exhibition which runs to the end of January (so no excuse for not going, or returning often). One of the more striking pastels there is the portrait of the future Mme Necker, on loan from the Schönbrunn in Vienna (above).

Or is it (4)? There seems to be no end to the stream of trivia and minutiae that can be unearthed about this fascinating artist (you can search with the box on the right the numerous posts here, at least ten since May, and many more have been silently incorporated into the online Dictionary articles) – the hunt no doubt stimulated by the current Royal Academy exhibition which runs to the end of January (so no excuse for not going, or returning often). One of the more striking pastels there is the portrait of the future Mme Necker, on loan from the Schönbrunn in Vienna (above).

The exhibition catalogue entry (no. 73) tells us that Liotard took it to Vienna in 1762 “and showed it to Maria Theresa, who convinced Liotard to sell it to her after he had made a copy for himself.” This isn’t I think quite accurate; and as the subject of Liotard’s copies and why (and when) he made them is of some interest, and as it is illuminated by a text which has not so far been noticed by art historians (as far as I am aware), I thought I would explore this in more detail. Confusingly the exhibition catalogue goes on to say “Perhaps because Liotard parted with this earlier portrait…he decided or was commissioned to paint another, probably in Paris.” The Schönbrunn pastel is dated “c.1761”; the second, “c.1772”, where the sitter is “about 12 years older”. (The chronology, p. 214, tells us that Liotard had left Paris for the Netherlands by July 1771.) This is the pastel in the château de Coppet:

It appears in the catalogue as no. 84, to be shown in London only – although in fact it didn’t make it to either London or Edinburgh.

There is evidently a little work to do to sort this out. Although we can do so by a careful reading of the documents already published in Roethlisberger & Loche’s 2008 monograph, “R&L” (indeed the key documents were summarised in the earlier, 1978 edition; and the date for the replica of the larger Mme Necker is given in my 2006 Dictionary), the story can now be illuminated by the diaries of Graf Zinzendorf. I draw the new material from the first four tomes of the new edition of Zinzendorf’s 56 manuscript volumes of diaries, edited by Grete Klingenstein & al., Europäische Aufklärung zwischen Wien und Triest. Die Tagebücher des Gouverneurs Karl Graf von Zinzendorf 1776-1782, Vienna, 2009. This is part of a major project: hitherto only parts have been printed (they are a mine of information about Vienna in the time of Mozart). I make no apology for interspersing this with extracts from Liotard’s correspondence that you can find in R&L, as many visitors to the RA exhibition may not have seen them.

The diarist was Joseph Karl R eichsgraf und Herr von Zinzendorf und Pottendorf (1739–1813), counsellor at the Treasury (Kommerzienrat) in Vienna 1762–66, Gouverneur of Trieste 1776–82, and later Staatsminister. Unmarried, he was a member of the Teutonic Order as you can see from the cross in this engraving.

eichsgraf und Herr von Zinzendorf und Pottendorf (1739–1813), counsellor at the Treasury (Kommerzienrat) in Vienna 1762–66, Gouverneur of Trieste 1776–82, and later Staatsminister. Unmarried, he was a member of the Teutonic Order as you can see from the cross in this engraving.

A version of this portrait is reproduced in Robbins Landon’s Mozart (1989 ed.) optimistically as by Füger (it is not in Keil’s catalogue raisonné); it is probably too late to be given to the unidentified pastellist from Ljubljana whom Zinzendorf records making his portrait in 1777.

Zinzendorf first met Liotard in Vienna in 1762: this entry for 12 July 1762, “Promené sur le rempart. J’y rencontrais Liotard avec Neker”, suggests that Zinzendorf had already met Liotard – and informs us that Liotard already knew Necker. Two years later, when he travelled to Geneva, Zinzendorf visited Liotard – as well as Voltaire, Cramer, Moultou, Deluc and others, all within the first fortnight of October 1764. (The full entries for this year will appear in the forthcoming volume edited by Grete Klingenstein with Helmut Watzlawick.) So when Liotard went to Vienna in 1777 it was unsurprising that their paths crossed again.

The scene is set almost completely in R&L: the Schönbrunn pastel (RA no. 73) is R&L 380, with a lengthy entry on pp. 532–34. The Coppet pastel (RA no. 74) is R&L 479, entry on p. 608, and, in the absence of documentation, is dated by R&L to the Paris trip 1770/71 (noting the possibility of an earlier passage to Geneva by the sitter). That must be right. But the entry that concerns us is for the copy that Maria Theresia permitted Liotard to make, which happened, not when she first purchased R&L 380 in 1762, but much later, when Liotard returned to Vienna in 1777/78. It has a separate entry, R&L 518, discussed in detail on pp. 643–44.

The reason for this later trip is perhaps not immediately obvious. Tronchin had warned him of the potential difficulties, and when Liotard got there (with his 19-year old son, Jean-Étienne fils), the 70-year old artist did indeed find it more difficult to obtain business: rivalry with Roslin (see my essay) was a particular concern. This ran both ways: on 22 December 1777 Roslin told Zinzendorf that “[il] regrette beaucoup de ne pas pouvoir faire le portrait de l’Empereur et de l’Impératrice Reine pour la reine de France, tandis que le barbouilleur Liotard va peindre toute la famille impériale et est logé à la Cour.”

But why did Liotard spend his time copying an old picture? It is easy to accept the analysis set out by the Empress Maria Theresia in a letter to Mercy-Argenteau in Paris (3 March 1780) in which she says that he can tell Mme Necker about her purchase of the pastel, and how, when Liotard was last [i.e. 1777/8, not 1762] in Vienna, “il a fait voir de la peine de n’être plus possesseur de ce tableau, et m’a demandé de pouvoir en tirer copie. Je le lui ai accordé, mais j’ai gardé l’original.” So, one might infer that Liotard wanted to make a copy of one of his earlier masterpieces, perhaps even as evidence or admission of failing powers (of imagination if not of technique). But as we shall see the reason was quite different.

Let us pick up the story in epistolary form. Liotard to his wife, from Vienna, 9bre [i.e.November] 1777: “…je retournai chez la Comtesse de Guttemberg [one of the Empress’s private secretaries] pour la prier de demander a l’Imperatrice la permission de copier le portrait de Me Necker…” [letter resumes later:] “Je viens de visiter le Baron Putcher [also a private secretary] qui nous a recue avec toute l’amitié me remerciant de lui procurer la veue de mon fils nous avons resté pres d’une heure avec lui il parlera Lundy à l’Imperatrice et lui demandera pour moi la permission de copier Me Neker.”

Liotard to François Tronchin, 19 November 1777: “j’ay dans ma chambre le portrait de Mme Necker je le trouve admirable pour la figure et surtout les accessoires mais je ne suis pas aussi content de la tête elle n’est pas assez belle les ombres du visage sont un peu trop fortes, en un mot je ferai tout ce que pourrai pour l’embellir sans alterer la resemblance.”

To his wife, 29 November 1777: “Joye excessive, nous avons été présentés a l’Imperatrice qui nous a recue mon fils et moy avec une bonté extraordinaire jusques a me faire assoir le voulant afin dit elle que je fusse plus pres d’elle, qu’elle avoit un très grand Plaisir a me voir comme ancienne connoissance et comme j’avois fair demander a copier de mes tableaux elle m’a fait conduire pour voir celui que je voulois et qu’on me l’enverroit quand je voudrois.” And to her again, 10 December 1777: “dans mes heures perdues je copie Me Neker qui me prendra bien du tems.”

To Tronchin, 6 January 1778: “la mort de l’Electeur de Baviere et le Carnaval je crois retarderont mes operations j’ay a peu pres fait la moitié de la copie de Me Nekers.”

To his wife, 7 February 1778: “Le portrait copie de Me Necker s’avance, mais il y a encore bien à le finir. J’ay fini le haut de la figure, les fruits, la soucoupe, le verre et le vin, la table est presque faite, j’aurai encore à finir le bas de l’habit, la main et le livre.”

Liotard to Tronchin, 14 February 1778, complaining about the lack of business: “je conte bien envoyer ma copie de Me Neker purement et simplement mais comment Mr Neker peut il etre informé que mon fils veut etre Negotiant Il faudroit qu’il seut indirectement que j’ay un fils de 19 ans et que je le destine au Commerce, ma coppie est au ¾ et il se passera plus d’un mois avant qu’elle soit finie.”

At this stage Zinzendorf comes in. On 18 February 1778 Liotard calls on the new Governor of Trieste (still in Vienna) and explains his purpose with complete clarity: “Le peintre Liotard m’amena son fils et me remit un billet de Sa Maj. L’Impératrice qui [m’ordonne] de l’écouter et desire de le consoler. Le fils, un grand garçon qui porta l’uniforme de Genève, a passé trois années dans une maison de commerce à Genève et voudroit, associé à M. Vial à Nice, commencer un petit établissement à Triest. Je lui parlois longtems sur ce sujet.”

A week later, on 25 February, Zinzendorf calls on Prince Waldek who is out, and then on Liotard, who is also out. We know from his son’s diary that Liotard went to dinner with General Bechard that day.

The next day, 26 February, Zinzendorf – and we – are in luck:

Chez le peintre Liotard. Il me fit voir en enthousiaste le portrait de Mme Necker qu’il a peinte encore fille, il y a vint ans, paroissant réfléchir sur ce qu’elle lit dans un livre relié en veau, qui a pour titre: L’Amour de la Vertu, appuyée du [coude] droit sur une table, où il y a une corbeille remplie de pêches, de raisins etc., un couteau, un petit pain, une caraffe de vin et un verre d’eau. De la main droite elle dérange son fichu blanc, parsemé de fleurs bleues et fait voir un peu de gorge. Elle porte un pet en l’air de satin bleu, et a selon moi l’air d’une énergumène. Liotard, logé à la Cour sous le duc Albert, me fit voir encore des portraits commencés de l’Empereur et des archiducs, qui sont horribles, un croquis de ce noble abominable. La seule bonne chose, c’étoit des essays de peinture sur le verre à l’ancienne.

The picture Zinzendorf was shown must I think have been the original version; the copy was not yet finished, as we learn from another letter from Liotard to his wife, 11 March 1778: “j’ay encore le quart du tableau de Me Neker a finir”. Nearing completion, a new problem arises (to his wife, 2 May 1778): “Je ne sai comment traiter Mr Neker dans la lettre que je lui ecrirai. Sil faut lui donner du Monseigneur ou non, je m’en informerai chez l’Ambassadeur de france ou chez le baron de fries.”

Finally, to Tronchin, 9 May 1778: “J’ay enfin fini le portrait de Me Neker, et je conte de l’envoyer incessamment la Caisse etant prette je lui ecrirai que je le prie de recevoir cette copie du portrait de son Epouze pensant quelle pourroit lui ester agreeable l’Imperatrice a été bien aize quand je lui ay dit quel portrait cetoit.” Presumably the original was by now to be returned: Liotard suggested that a group of his best pictures, including Mme Necker and L’Écriture (also shown in the Royal Academy exhibition, no. 76), be placed with the best of the Imperial Collection in the Belvedere, but his proposal was rejected by Joseph Roos, directeur de la galerie impériale, who evidently thought they were not good enough.

The copy of Mme Necker was duly dispatched to her husband in Paris. Liotard was prevented from travelling with it by the build-up of military tensions between Prussia and Austria. What one wonders was her husband expecting? He presumably knew the Coppet pastel, but he cannot have seen the Schönbrunn portrait. We must infer his response from his conduct. The picture (on which Liotard had lavished six months’ work) is not at Coppet, and indeed was never seen again. Necker did not arrange a preferment for Liotard fils; instead he sent a polite letter and a payment of 25 louis, much to the son’s disgust (he thought the picture worth 60 louis; 25 louis was in line with ordinary small portrait prices, but about one-tenth the 200 guineas which Lord Bessborough had paid for Le Petit Déjeuner des Mlles Lavergne in 1755). The scheme in short had failed.

What do we learn from this new document, apart from this very clear explanation of Liotard’s strategy? One small detail immediately: the title of the book remains today quite difficult to decipher (although the pastel has been extensively restored in the past, I don’t think this area was altered). R&L interpolated “LAM[OUR] DE [LA] VERTU”, and (once again) they are proved right: the title of the book, or at least what Liotard said it was, was L’Amour de la Vertu. Note both the subject and the duodecimo format of the book.

But there is also a fascinating reaction from a visually literate, if non-specialist, contemporary witness. For him it was the new things Liotard was doing that were “abominable”. He doesn’t share Liotard’s own enthusiasm for Mme Necker, but nor does he particularly disparage it. He comments specifically on her flirtatious rearrangement of her fichu. Liotard’s only criticism of his picture when he sees it so many years later is that the shadows on the face are too heavy: that is not what strikes us. But Zinzendorf does make one specific observation which I think gets to the heart of the issue: as he sees it (he does not suggest that Liotard does so), the sitter has the “air d’une énergumène”. The word isn’t particularly common in English either, but an energumen is a fanatical devotee: devilish possession is the key ingredient. It’s a more interesting suggestion than what may be our immediate response: both this and, to a certain extent, the later pastel seem to show a rather unintelligent, almost bovine face that could hardly contrast more severely with the wonderfully elegant and sophisticated depiction by Duplessis:

Was this type of portrait what Necker was expecting? If he had been told that his wife was shown with a book, would his sophisticated eye not have imagined something more like Mlle Ferrand whom La Tour shows pondering over her in-folio Newton:

“La belle Curchod” we must remember was one of the most brilliant women of her age, one who had captivated two of the most intelligent men in Europe – Edward Gibbon and then Jacques Necker, and she would be the mother of the formidable Mme de Staël. Gibbon, who was forced by parental opposition to break off their engagement in 1758, tells us that her “personal attractions …were embellished by the … talents of the mind”; he found her “learned without pedantry”; her beauty “was adorned with science and virtue.” (As we learn from his diaries, Zinzendorf was actually reading Gibbon at the time of his visit to Liotard; he doesn’t tell us if he was aware of the girl’s past.)

But perhaps we should return to the first version. The pastel must have been made between the sitter’s move to Geneva (some time after the death of her father, 17 February 1760) and Liotard’s departure for Vienna in April 1762. In Geneva she lodged with Pastor Moultou where she later met Mme de Vermenoux, visiting Dr Tronchin in the city (despite numerous biographical studies, there seems to be no agreement on the exact date of their meeting; it may even be that Curchod introduced Liotard to Vermenoux rather than the other way round as normally assumed). Gibbon tells us that the Duchess of Grafton had nearly hired her as governess, but it was in that role that she would accompany Mme de Vermenoux to Paris in early 1764 (missing Zinzendorf when he dined with Moultou later that year). But at the time of the pastel, we know that she still entertained hopes that Gibbon would relent. (Suzanne was born on 2 June 1737, so marriage was becoming an urgent issue for her: but she would not have had the funds to commission this as an advertisement even had she regarded herself as available.) On his return to Switzerland in 1763, Gibbon was not alone in detecting an element of insincerity in her “false, affected character.” A taste for the theatre, and for theatricality, had taken hold; and when she was about to go to Paris with Mme de Vermenoux, her supporter, the duchesse d’Enville, wrote to Moultou from Paris (17 February 1764), to warn him that these characteristics might not go down too well in Paris:

Je suis bien aise que Mlle Curchod ait trouvé une place, en doutant cependant qu’elle soit aussi heureuse ici qu’elle était à Genève. Simplifiez-la pour son arrivée; elle ne réussira ni avec sa métaphysique ni avec sa coiffure; au nom de ciel, simplifiez-la!

The precise circumstances of Liotard’s first portrait remain unclear. For Liotard it was probably (and would be seen by Maria Theresia as) essentially a genre picture rather than a portrait: a showpiece exhibition of his skills. But it is clear that Liotard captured – without the recommended simplification – just this element of provincial histrionics that she was advised to leave behind in Geneva. This Dorothea Brooke narrowly avoided being crushed by a damn’d thick square book. But in sending his repetition to her husband, did not Liotard attempt to strangle her with another damn’d thin light one?

Francis Sykes after Liotard, Princess Elisabeth Caroline (Royal Collection)

When I was a publisher many years ago, I was privileged to have on my list (and to have the benefit of his advice) Dr John Sykes, physicist and lexicographer, and one of the most brilliant minds I have come across. I have no idea if he was connected with the family of the enamelist Francis Sykes, but his great celebrity as the most consistent winner of The Times crossword championship pointed to a skill that would certainly have helped unravel the story I set out below, and which I stumbled across while hoping (in vain) to establish the identity of an unrelated pastellist.

The information in various reference books contains a number of confusions, and the story can only be told by consulting a very wide range of sources, some of which contain material errors and omissions which ought to be corrected – not least because on the authority of the famous antiquary Ralph Thoresby, who was related to the family, a descendant was denied the arms to which he was entitled. Civil war tensions combine with undocumented life events for the crypto-Catholic branch of the family. Unlike crosswords, art historical research should end up with a story which is more interesting than the puzzles that obscured it (and worthwhile even when incomplete), so I shall present the outline of a story in a linear narrative. I don’t think it has been pieced together before. It may I hope inspire others to add some missing components.

You can find an extended pedigree with the principal biographical data on my website at this link.

The story starts in Leeds, with Henry Sykes (1601–1654) of Hunslet Hall. His son William was a republican, which partly accounts for the omission of this branch of the family from genealogical accounts. William’s fifth son Daniel (1632– ) was the father of the Richard Sykes who married the heiress to the Sledmere estates, from whom the well-known family of Sykes of Tatton descend (they are the subject of numerous eighteenth century portraits by Gardner, Romney etc.). But the fourth son, also William, was written out. And it is to that William’s son, yet another William, born 1660, that we must turn.

This William appears in Thoresby simply as a merchant who died without posterity in 1692. Thoresby must have known this was untrue as he was married to William’s cousin Anne, as you can see from the Sykes pedigree which he prints in his Ducatus Leodiensis, 1715, p. 4 (to be compared with mine linked above):

This William Sykes, “limner”, was involved in an altercation in which he killed two bailiffs at his house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, for which he was convicted of manslaughter on 17 January 1697/8. But he remained in business, both as a painter and as a dealer in paintings, playing a significant role in the Virtuosi of St Luke and acquiring a reputation as a connoisseur.

Sykes appears on several pages in Vertue’s notebooks, for example (i.52) “Mr Bullfinch Bought all Mr Betterons Pictures amongst which were a great many Crayon pictures of famous Playerses these he sold to Mr Sykes.” His death, which took place in Bruges on 31 December 1724 (Vertue noted “Mr Sykes dy’d at Brugs”: i.146), was reported first in the Daily Post, 12 January 1725:

Soon after, his collection of 300 or so pictures were sold over five days from 2 March 1725 at his house, the Two Golden Balls, Portugal Row, Lincoln’s Inn Fields. The quality of the collection is revealed in the catalogue which can be seen in full on the excellent website artworld.york.ac.uk at this link.

The disposal of the pictures was in conformity with his will (Gulielmi Sykes of the parish of St Giles in the Fields, painter) which was proved 11 February 1724/5 (National Archives, Prerogative Court of Canterbury). In it his wife, his sons William and James and his grandson Luke are mentioned. William took over the business, but himself died three years later. This time the will (proved 23 May 1728) contains a number of clues that have been overlooked. Notably he again provides for his pictures to be sold, but the proceeds are to be used for the benefit of his two sons, Francis and Luke: each is to be “apprenticed to an able Master in Painting”, but he specifies that that master should, in the case of Luke, be “Mr Wootton”, and in the case of Francis, “Sir James Thornhill”. Both sons were therefore probably below the age of 14 when the will was made (11 March 1727):

The auction took place at Cooper’s, Covent-Garden, 23 January 1728/9 and following days. This was announced in the Daily Post, 14 January 1728/9, and again the catalogue can be consulted at this link: https://artworld.york.ac.uk/artworld/sourceView.action?sourceUrn=5.0155.2&br=no .

This followed what must have been an unseemly row between members of his family, resulting in this notice in the Daily Journal, 8 November 1728 (repeated a week later):

Little more is known of James. The Daily Journal for 30 August 1731 reported that he was “attacked by three Street-Robbers, at the Corner of Duke-street, near Vere-street, but he making a brisk Defence, and others coming to his Assistance, they thought fit to make off.” He died in 1737, according to a piece in Notes & Queries, 1882: but this may be an error (see below), as the will proved on 13 April contains no information definitively identifying his relationships.

Of Luke Sykes nothing more in known. But our story resumes with his brother Francis Valentine Sykes (1715–1771), a miniaturist of considerable distinction whose biography has hitherto been completely unknown.

His date of birth and full baptismal names are provided by a James Sykes (writing in Notes & Queries 1861–1882, as QFVF, initials based on the family motto), who is unaware that his ancestor was an artist.

It isn’t certain if Francis Sykes was taken on by Thornhill, as his father intended. Rather the first sighting we have is from two engravings made after Thornhill’s son-in-law William Hogarth: an undated portrait of the actor John Hippisley as Sir Francis Gripe, and this engraving after one of Hogarth’s Four Times of Day:

Sykes’s plate, known as “The Half-Starved boy” (reproduced from the Metropolitan Museum of Art impression), is inscribed “WH pinx. F. Sykes sculp. 1730”, leading to a dispute about the year: 1738 or 1739, being suggested, e.g. by Hogarth’s biographer John Nichols (who was also unsure if Sykes was a pupil of Hogarth or Thornhill). However the best testimony about Sykes’s training (and the main clues to the puzzle of his identity) are given by the artist himself, as reported in the Diary of Sylas Neville 1767–1788 (Oxford, 1950, p. 84 & passim), who knew Sykes at the end of his life. Apparently “Hogarth for water-colours [sic] and Zink for enamel were Mr. Sykes’s masters” (he also taught Samuel Cotes, and esteemed “the elder Cootes the best artist in Crayons”).

We don’t know at what date he studied with Zincke, but it seems that quite early (before 1740) he was married, to a Theresa Rigmaden or Rigmaiden (1713–1791), the daughter and heiress of Francis Rigmaden of Twickenham. Her ancestry plays a crucial role in unravelling the story: one of the remarks that appears in various sources is that Sykes was a descendant of the man who hid Charles II in an oak tree at Boscobel after the battle of Worcester. In fact the descendant was Theresa, not Sykes; but even here the sources were garbled, as a flurry of insertions in Notes & Queries in the late nineteenth century revealed. Some propagated the idea that Theresa was a Pendrell, the name of several of those loyalists who concealed the king; but in fact her ancestor was Francis Yates, another of those involved. All of this matters because the grateful monarch rewarded these men with perpetual annuities of £100, to pass to their lineal descendants; with the result that there are extensive files proving their genealogies in the National Archives (summaries are printed in several books about the Boscobel incident). They are the basis for much of the information in this post.

We know that Sykes had settled in The Hague by 1743, when, on 27 August, he registered his will there. A son, also Francis, was born c.1740, and was last recorded in India c.1764, where he is thought to have died (although a Francis Sykes married a Catherine Ridley in Calcutta in 1766, possibly no relation). But the most important member of the next generation, Francis’s second son Henry Sykes (see below), was born in The Hague in 1743/44; a daughter Theresa was born in 1749. It is clear that the family’s connections with The Netherlands had not ended with William’s death : Francis’s aunt Ann Sykes is reported to have founded a convent in Bruges, where she was still living in 1740.

By 1752 Sykes was in Paris, for reasons that will emerge. Here he was recorded as purchasing a large group of miniatures by Petitot at the sale (from 27 November to 22 December) of the banker Cottin, apparently for resale back in London. He appeared a few years later in Les Affiches de Paris in 1754 as “peintre miniaturiste du duc d’Orléans”. But he led a hand-to-mouth existence, living in a furnished room in the rue du Petit-Lion, unable to pay his rent or his suppliers, and spending his advances before delivering his work. Thus in 1752, the goldsmiths Garand and veuve Ravechot consigned to him a gold box to be enamelled for the maréchal de Richelieu, and advanced him 1747 livres. Three years later Sykes had spent the money without commencing the work, and refused to return the box. The maréchal set the lieutenant de police on to him, and had Sykes imprisoned in the Bastille until he agreed to finish the work. (Henri Lapauze, in the journal La Renaissance, 1924 tells the story, but confuses the artist with one George Sykes, an artist later known for his expertise in drawing portraits on board with a red hot poker; the confusion persists in the reference books.)

Essentially the same story was told very differently by the artist himself, to the actress George Anne Bellamy (c.1731–1788). The background to the story was reported London Evening Post, 4 September 1755: a certain Peter Sykes, formerly an eminent merchant, who died in Toulouse on 19 August 1755, had left his fortune equally to Bellamy and a “James Sykes, a resident of Utrecht” (who one speculates might be the uncle of Francis reported as dead in 1733). According to her own account (in her Apology…), Bellamy, who was habitually short of funds, was surprised to be told by a friend that her “fortune was made”, before reading a newspaper report to her concerning the death, “a short time before” of “Thomas Sykes, Esq” [sic] who “had died in the South of France, and had left his fortune in the English funds, and his property at the Hague, both of which was supposed to be very considerable, to Miss Bellamy, belonging to one of the theatres.” Bellamy’s unsuccessful attempts to recover this legacy are related in her autobiography; the funds were ultimately confiscated by the Dutch authorities. Some time later, finding herself in Antwerp, she pursued the matter with Mr Sykes’s brother [sic]: this must have been Francis. There she

learnt that Mr Sykes, (who, besides his profession as a painter, kept a jeweller’s and bijou shop) having had an invitation from the Duke de Berry, in order to make some alterations in his Grace’s gallery, was gone to Paris. Some other great personage taking offence at Mr Sykes’s giving the Duke the preference to himself, had procured a Lettre de cachet against him. And as he was one day at the coffee-house, an exempt took him aside, and desired he would take an airing with him, in a coach which stood at the door, as far as the Bastile. It would have been in vain for him to resist, and equally as vain to enquire the reason. He had only time to request of a gentleman of his acquaintance, who was in the room, to let his wife know of the disaster. This his friend did; and it had such an effect upon her that she lost her senses in consequence of it. Such being their unfortunate situation, it was much feared neither Mr nor Mrs Sykes would ever return to their family more.

Soon after, Sykes reappeared in London, where three notices appearing in the Gazette between 30 March and 10 April 1756 (as the bankruptcy law required) explain the reasons for his stay abroad:

Back in London he resumed his practice as an enamelist, creating a small number of miniatures which are mostly only attributed to him. One signed example is this very fine 1759 enamel, in 1917 (when this terrible photo was taken) in the collection of Ernst Ludwig Großherzog von Hessen und bei Rhein (to whose mother, Princess Alice, it was bequeathed by Princess Sophie Matilda of Gloucester (1773–1844), her godmother):

Francis Sykes after Liotard, Princess Elizabeth Caroline, sd 1759

A second version, not signed or dated, is surely also by Sykes, and is still in the Royal Collection; reproduced at the start of this post. Although not remarked in the Royal Collection online database, the image derives from Liotard’s well-known pastel of the princess – but with a change of dress, so that it matches the pastel copy of the Liotard also in the Royal Collection:

The date of the Hesse enamel, 1759, is some six years after the Liotard; it may be that the copies were made on the princess’s death in that year. It is probable that the other enamel was made at the same time, and surely by Sykes. The authorship of the pastel copy is not known: but the substitution of the blue dress for the highly complicated shot silk in the Liotard may well have had the enamels in mind (the blue is the same as that found in so many enamels by Sykes’s teacher Zincke), and it is quite possible that Sykes himself made it. There is however no other evidence that he used pastel.

Of Sykes’s other enamels one can cite one of the Earl of Bute, sd 1760 (another of the same sitter, after Ramsay, is in the V&A, attributed), as well as a portrait of George III, sd 1764 (Christie’s, 13 February 1962, Lot 28).

The Morning Chronologer for 4 May 1764 [in the London Magazine, June 1764, p. 325, followed by other papers, but the dates given erroneously in various references as 1769] contained the following announcement:

“F. Sykes” was among the 211 artists who subscribed the Roll Declaration of the Incorporated Society of Artists of Great Britain in 1765.

For the remainder of Francis Sykes’s career, the best coverage is the rather sorry picture painted by Sylas Neville, who clearly found the man very engaging, and reports their numerous conversations in some detail, and, one suspects, some inaccuracy. Thus when Neville “introduced a conversation about Charles Wortley Montague”, the figure Sykes describes is not Edward WM (as the editor of the diary assumes), but Liotard (the story is of course of the beard, and the legend of his admission into the seraglio where “he painted all the ladies in crayons”). The artist recommended Montpellier, where he may have lived at some stage. Sykes guided the young miniaturist Edward Miles, who drew Neville’s portrait. Sykes’s enamel of Neville, “one of the best he had done”, shows the diarist in Vandyke dress, the colour dark grey, sleeves and breast slashed with crimson; in the foreground, an ancient urn inscribed DMGG for Diis Manibus Gracchorum. (The description suggests that the enamel of a lady in Vandyke dress sent to the Society of Artist in 1761, no. 116, was surely by the same Sykes.) Neville ended up reluctantly accepting Sykes’s bill for £60, whereupon, with the bill unpaid, Sykes died, in Yarmouth: between 30 July 1771, when Neville last saw him, and 3 August, when he was already dead (“of an uncommon disorder”) and buried. Only after this does Neville learn the extent of Sykes’s hardship and distress; a friend explained that Sykes “was once in a very good way in Holland and did what he pleased about pictures, but that he could not rest there, but would go to see Paris.”

Neville, who was surprised to be told that Sykes was a Roman Catholic, also mentions two daughters, one “pretty well married”, the other in a nunnery abroad. He makes no mention of the sons. As noted above, Henry Sykes was born in The Hague in 1743/44. He was still in London when, c.1766, he married Grace Birch (1744–1812), the daughter of Francis Birch of Uppingham (and it was in Uppingham that Henry’s mother Theresa died in 1791). Although Henry retained a presence in England (at The Crescent, New Bridge Street, Twickenham), he settled in France, where he conducted an important and broadly based business. This included spinning and textile manufacture, at Saint-Rémy-sur-Avre, but branched out into the retailing of luxury goods from premises in the Palais-Royal. Here, while recorded as a mercier (baronne d’Oberkirch took her daughter there to buy fabric) and selling prints, he developed a speciality in importing scientific instruments from Britain, earning him the title “opticien privilégié du roi”. Thiery 1788 noted his “magasin de physique, estampes angloises & autres curiosités, chez M. Sykes, place du Palais Royal.” His suppliers included the renowned firm of Peter Dolland (the maker of telescopes used both by John Russell and Maurice-Quentin de La Tour), and he supplied spectacles to Benjamin Franklin (allegedly the first set of bifocals). Before he became known in a different context, Jean-Paul Marat conducted scientific experiments using apparatus which he would only allow Sykes to construct. (In France the spelling causes some difficulty, and variants such as Sikes or Sickes occur.) But it was as a symbol of frivolous spending that Sykes appeared in the satirical verses of the chevalier de Cubières (Opuscules poétiques, 1784):

Most sources have Henry’s only child as Grace Valentine (1768–1817), whose marriage (which took place in London, St Anne’s, Blackfriars, in 1788) to another expatriot, William Waddington, produced a line of French parlementaires, including her grandson, William Henry Waddington, Prime Minister of France in 1879.

The story remains incomplete, with a number of loose ends. Of these the most puzzling is the relationship (if any) with George Sykes, Jr mentioned above: he exhibited portraits (not all with the red hot poker) and a conversation piece at the Society of Artists 1770–73. In 1773 he wrote to George Stubbs to request election to the Society, and he appears then to have settled in York. There is a curious reference in William Paulet Carey’s Letter to I*** A***, a connoisseur in London, Manchester, 1809, ii, p. 25, in which he attributes an anecdote about Richard Wilson (that he used a large decayed cheese to model for rocks and landscapes) to “Mr Sykes, an Artist of merit, who now lives, beloved and respected, in York; and who, forty years ago, painted pleasing portraits, in miniature and oil; and small conversations, composed with much elegance of fancy.” There is no obvious connection with Francis Sykes and his family.

Postscript (2 July 2023)

Catriona Seth has drawn my attention to a slightly cryptic postscript to a letter from George Innes in Paris to James Edgar in Rome 25 Oct. 1750 (SP MAIN 312/30):

P.S. I was sadly disappointed, not knowing in time Miss Reads departure, which would have been an excellent occasion for transmitting papers to Mr Lumisden (to whom my humble service.) They were left with mr Syke’s Br[other] in Law, who of all the portraits I ever saw of the Prince, has made the completest one in the judgment of all who have compar’d it with others made of HRH in this town.