L’Écriture deciphered

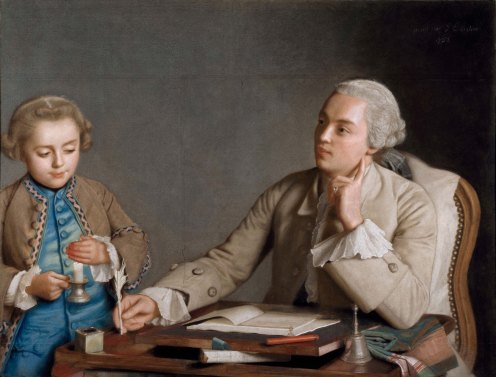

[NB: This post has been superseded; please instead consult the revised version of record http://www.pastellists.com/Essays/Liotard_LEcriture.pdf .]Those of you who saw the Liotard exhibition at the Royal Academy in 2015 will not have forgotten one of the finest exhibits – the stunning pastel of a young man writing with a boy in attendance holding a candle.[1] It was sold to Maria Theresia in 1762, ten years after it was painted, and so its permanent home is now Vienna. Its connection with the famous Déjeuner Lavergne (J.49.1795: see my post) of 1754 is obvious, despite the two-year interval between their execution: the visual evidence is overwhelmingly that the latter was conceived as a pendant, and this is confirmed by the advertisement in the London Public advertiser that I reproduced in the earlier post. There is no doubt either that the Déjeuner was executed during a trip to Lyon in 1754 – indeed another Lavergne family portrait was done there in 1746 – as there is other corroborative evidence of Liotard’s visits to his sister and her family: Sara Liotard had married the négociant François Lavergne in Geneva before they settled in Lyon. All this is rehearsed in my previous post, so I won’t repeat it here.

[NB: This post has been superseded; please instead consult the revised version of record http://www.pastellists.com/Essays/Liotard_LEcriture.pdf .]Those of you who saw the Liotard exhibition at the Royal Academy in 2015 will not have forgotten one of the finest exhibits – the stunning pastel of a young man writing with a boy in attendance holding a candle.[1] It was sold to Maria Theresia in 1762, ten years after it was painted, and so its permanent home is now Vienna. Its connection with the famous Déjeuner Lavergne (J.49.1795: see my post) of 1754 is obvious, despite the two-year interval between their execution: the visual evidence is overwhelmingly that the latter was conceived as a pendant, and this is confirmed by the advertisement in the London Public advertiser that I reproduced in the earlier post. There is no doubt either that the Déjeuner was executed during a trip to Lyon in 1754 – indeed another Lavergne family portrait was done there in 1746 – as there is other corroborative evidence of Liotard’s visits to his sister and her family: Sara Liotard had married the négociant François Lavergne in Geneva before they settled in Lyon. All this is rehearsed in my previous post, so I won’t repeat it here.

I might add that the abbé Pernetty, whose portrait by Liotard was also made in 1754, returned the compliment by mentioning the artist as well as “Mrs Lavergne, établis ici, & connus par leurs talens” in his Les Lyonnois digne de mémoire (1757, p. 255). The MM. Lavergne were of course François, who died in 1752; his eldest son Jean (1715–1776), also described as a négociant on his burial certificate (most sources, including R&L, incorrectly thought he had died in 1729); the son [probably] shown in L’Écriture, Jacques-Antoine (1724–1781), described as a banquier on his (but the professions were not much different: the Almanach des négocians for 1762 lists the firm among “banquiers, négocians en soye et commissionnaires” in Lyon); and the youngest son Hugues (1732–1768), unknown to R&L. For R&L the young man in the pastel must therefore be Jacques-Antoine.

Although that document gives nothing away, Marie-Félicie Perez published a note in Genava in 1997 with an entry from the unpublished manuscript diary[2] of the abbé Duret in which he reveals that Jacques-Antoine committed suicide by throwing himself out of a window. No one knows why – Perez checked for a declaration of bankruptcy, but could find nothing. The catalogue of an exhibiton in Lyon in 2012 consequently found the picture ”tout imprégné de rêverie mélancolique”.

Nor frankly does any of the Liotard literature tell us anything of the biography of this young man. Indeed earlier authors spotting the book whose title, L’Art d’aimer et de plaire, is so carefully shown in the pastel concluded he must be a poet, and identified the sitter as Pierre-Joseph Bernard who published a book called L’Art d’aimer – but failed to notice that it didn’t appear until 1775, and that in 1752 Gentil-Bernard (as he was known) was already 44. (Indeed of Liotard’s three nephews, it is the apparent age of the sitter that identifies him as Jacques-Antoine (28 in 1752) rather than his brother Jean – not dead, but at 36 too old; but can one be confident that it is not the youngest brother Hugues, who would have been 19?) Of course that doesn’t mean that Liotard’s sitter didn’t also have literary aspirations: it’s just that, until now, no one has produced any evidence. Was he then just a boring banker?

And as for the boy, predictably described as the nephew’s nephew in some sources, and therefore named Clarence (as the girl in the Déjeuner as previously thought to be), that is far from certain (but it was not impossible that he could be the Pierre Clarenc [sic] who was born in Lyon on 16 January 1744 – his baptismal entry only discovered in 2023 – and married in Puylaurens in 1771). But I’m inclined in this case to believe Liotard when he calls the boy a “laquais”, and I don’t think he’d so describe a member of his family.[2a]

L’Écriture, as the 1752 pastel is known, is signed and dated with the year – but not the place. And while everyone assumes it was made on a trip to Lyon, that might not necessarily be correct. If Jacques-Antoine went to Paris, which he might well have done, then the boy would almost certainly be unrelated. On the other hand, if you think that he is the same child as in the L’Enfant à la bougie (J.49.2441) that I published a few years ago (also reproduced in my Déjeuner post), he probably did come from Lyon, as that pastel was reported (again by the abbé Duret, as spotted by Perez) in 1781 as having previously being bought by Mme de Flesselles for her husband, the intendant de Lyon from 1767 on. Roethlisberger & Loche inferred from the subject matter that it might belong to the period of L’Écriture, and with the image I found I concur. So it’s possible that it was left with the Lavergne family in Lyon and it was only disposed of between 15 and 30 years later.

So far virtually everything I’ve repeated here is known – and it’s not very much. The diary of Jean-Jacques Juventin which I recently added as a postscript to my Déjeuner post talks only about the Lavergne ladies, and tells us nothing of the men. Nor, despite its usual encyclopaedic coverage, does Lüthy (La Banque protestante…) even mention the firm. There’s a tiny snippet in a letter[3] from Louis-Michel Vanloo’s sister, Marie-Anne Vanloo Berger, from Paris, 20 April 1757, to his partners Antoine Rey and Barthélemy Magneval, merchants in Lyon, describing how she had missed M. Lavergne who had called that morning, and promising if he returned to receive him as well as she could as he was their friend. At least this proves that Lavergne travelled to Paris occasionally – but that is hardly surprising for a négociant.

But I recently noticed a source which as far as I can see has been completely overlooked in the Liotard literature: Voltaire’s correspondence.[4]

There is only one Voltaire letter directly addressed to the Lavergnes, but several to his other friends give their name (as “Lavergne père et fils” etc. – no first names ever appear) as an accommodation address. But there are three letters with specific information. In one (8 May 1773) to Joseph Vesselier, a poet and writer whose day-job was with the Lyon post office, Voltaire noted that “un de ces Lavergne … joue parfaitement la comédie”. In a letter to Trudaine de Montigny (12 April 1776), then travelling to Nice, he adds more:

J’avais un ami genevois qui s’appelle Lavergne, excellent auteur, dit on, dans les comédies de société. Il était malade à Lyon et désespérait de sa vie, il est allé à Nice et y a recouvré la santé. Je ne sais s’il y est encore, et s’il a eu le bonheur de vous faire sa cour.

Tantalisingly Voltaire doesn’t identify which of the Lavergne men this amateur actor, writer and invalid might have been. Was it our Jacques-Antoine, or his elder brother Jean? We have another clue in a letter Voltaire wrote, the next day, this time addressed directly to Lavergne Frères:

J’ignore, Monsieur, si Monsieur vôtre frère est encor à Nice. En ce cas il doit avoir passé des jours fort agréables avec Mr De Trudaine, intendant des finances, Made De Trudaine, et Mr De L’Ille mon confrère, qui sont allés chercher la santé dans le même coin du monde. J’aurais bein dû faire ce voiage; mais je suis trop vieux pour me transplanter.

To identify which brother, I found another report – a 1773 account of the health-giving properties of the thermal waters not at Nice, but at Aix, by the celebrated doctor Joseph Daquin (who was best known for his work in psychiatry). Here it is in full (remember Jacques-Antoine would have been 48 or so, near enough 50, while his brother was eight years older):

![Analyse_des_eaux_thermales_d'Aix-en-Savoie_[...]Daquin_Joseph_bpt6k5853688n_150](https://neiljeffares.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/analyse_des_eaux_thermales_daix-en-savoie_...daquin_joseph_bpt6k5853688n_150.jpg?w=497)

![Analyse_des_eaux_thermales_d'Aix-en-Savoie_[...]Daquin_Joseph_bpt6k5853688n_151](https://neiljeffares.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/analyse_des_eaux_thermales_daix-en-savoie_...daquin_joseph_bpt6k5853688n_151.jpg?w=497)

From the age I inferred (in an earlier version of this post) that this was more likely the younger brother Jacques-Antoine. The condition described was severe enough to merit Voltaire’s description of a man despairing of life, particularly if after the cure the symptoms returned. That rather than financial failure might well have led to his suicide. But I’ve since come across new evidence: in the Archives de la Charité de Lyon (Inventaire sommaire…ville de Lyon, iv, 1880, p. 156) there is a certificat de vie, delivered in 1774, supporting the purchase of an annuity by “Jean Lavergne, négociant de Lyon, qui se trouvait alors dans la ville de Nice … jouissant d’une rente annuelle et viagère de 1,225 livres, sur l’hôpital de la Charité.” So it now seems clear that the brother who went to Nice and was the comedian was actually the elder, Jean, not Jacques-Antoine.

This undermines the argument in the earlier version of this post, that Voltaire’s description proved that the Écrivain in the pastel was indeed a writer, that the sense of intelligence with which he ponders his material is real etc. Nevertheless the information describes the family milieu in which this young man is depicted, and while he may not have himself been a talented actor, there is nothing to disprove an interest in writing more broadly than the commercial tasks of a négociant. We can at least be certain of one thing: Liotard’s Écrivain was one of Voltaire’s correspondents. If any of his brother’s literary work was ever published it was certainly not under his own name, but his interests were plainly in plays. What then can we make of the carefully planted copy of L’art d’aimer et de plaire, hitherto assumed to be purely fanciful?

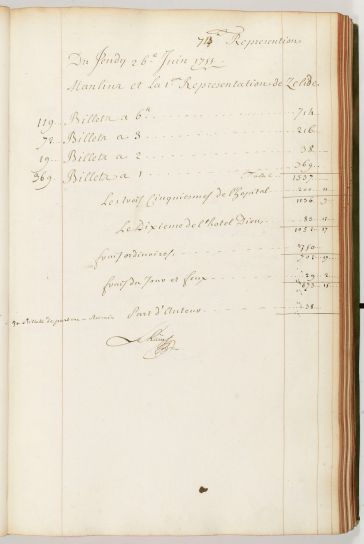

I had previously identified it as the subtitle of a play called Zélide, but that was only published in 1755 and the dates still don’t quite work. It was written by one Jean-Julien-Constant Rénout, who was secrétaire du duc de Gesvres (the duc had commissioned Pierre Mérelle to copy Liotard’s portraits of the royal princesses in 1751). But although not premiered until 1755,[5] there was apparently an earlier performance of Zélide at the comte de Clermont’s château de Berny, probably by an amateur cast. (Liotard’s pastel of the comte de Clermont was recorded in the artist’s posthumous inventory.) It is of course sheer speculation, but might Jean, who played “parfaitement la comédie”, have had an advance manuscript copy for amateur use – and shared it with his younger brother?

I had previously identified it as the subtitle of a play called Zélide, but that was only published in 1755 and the dates still don’t quite work. It was written by one Jean-Julien-Constant Rénout, who was secrétaire du duc de Gesvres (the duc had commissioned Pierre Mérelle to copy Liotard’s portraits of the royal princesses in 1751). But although not premiered until 1755,[5] there was apparently an earlier performance of Zélide at the comte de Clermont’s château de Berny, probably by an amateur cast. (Liotard’s pastel of the comte de Clermont was recorded in the artist’s posthumous inventory.) It is of course sheer speculation, but might Jean, who played “parfaitement la comédie”, have had an advance manuscript copy for amateur use – and shared it with his younger brother?

Postscript (12.ix.2023)

Although not immediately relevant to the Liotard pastels, there is a curious incident in the family background which is worth noting. As we know, Liotard’s sister Sara married François Lavergne (1678–1752) in 1713. The family name was in fact Mialhe, and he was the son of Daniel Mialhe La Vergne, from Vabre near Castres. His brother Philippe Mialhe de Lavergne (Vabre 1687 – Lyon 1761) was in Paris on 13.ix.1720 when he contracted to marry a 46-year-old heiress, Marie Goussard de Ménard (1674–1757), daughter of a huissier audiencier aux finances de Tours, bringing a dowry of 28,000 livres. But for reasons that remain obscure, the marriage never took place, and Marie went back to the notaries two years later to report this. She bought an annuity instead, and died in a convent in Paris 25 years later. Liotard seems to have had no contact with Philippe in Paris at this time. Philippe subsequently lived with his brother in Lyon, and his inventaire does not indicate any great wealth.

[1] L’Écriture is J.49.1763 in the online Dictionary of pastellists, where as usual full details can be found (just put the J number into the search box and follow the link to the pdf).

[2] In the municipal library at Lyon.

[2a] [Postscript:] I am grateful to Chris Bryant who has pointed out that the boy’s coat, with its braided edging, is servant’s livery.

[3] Georges Guigue, Vanloo négociant, 1902, p. 24.

[4] The easiest way to consult this is via the Electronic Enlightenment website, so the dates alone will find the passages I mention. One of Voltaire’s correspondents was the pasteur Jacques Vernes (also a friend of Rousseau) who married Jacques-Antoine’s 18-year-old niece Marie-Françoise Clarenc in 1759; she died later that year. One further reference appears in a letter from Charles Palissot de Montenoy to Jacob Vernes of 15 March 1756; writing to his friend to ask him to interecede with Voltaire on his behalf, he promises to send him a copy of his “histoire”, via “M. Lavergne”, unidentified in Electronic Enlightenment, but surely Vernes’s soon-to-be brother-in-law.

[5] To a mixed reception: in a letter from Claude-Pierre Patu to David Garrick written from Passy, 23 August 1755, he notes that it had “Assez d’esprit, peu de justesse, style haché, mauvais tour de vers.” The extract from the Comédie-Française’s register show the receipts for the double bill on 26 June 1755.

.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks